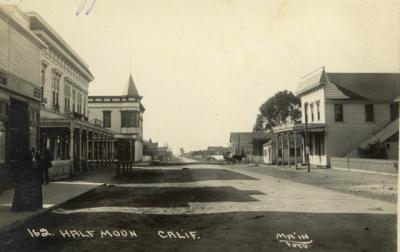

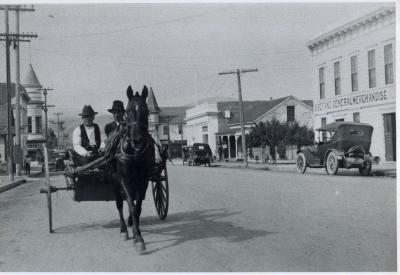

Of course, it’s authentic Half Moon Bay. What a great look!

photo: Spanishtown Historical Society, Johnston Street, Half Moon Bay (look for the little jail)

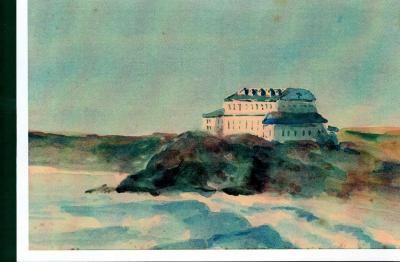

Loren Coburn’s Folly: Pescadero’s Pebble Beach Hotel

In the 1890s Loren Coburn, the most hated man in Pescadero, built the Pebble Beach Hotel overlooking the popular and locally sentimental pebble-covered beach south of the tiny village. From what we know guests never stayed overnight– except for the watchman who was there to protect the new hotel from vandalism. (Among modern conveniences the Pebble Beach Hotel offered the luxury of hot and cold water). Business associates of Coburns (perhaps anxious to take advantage of the illiterate but wealthy man) sometimes held private parties at the hotel.

Local artist Galen Wolf wandered up and down the Coastside using his box of watercolors to preserve the past for us. Here, before it was torn down to make way for Highway 1, is Wolf’s picture of Loren Coburn’s Folly: the Pebble Beach Hotel at Pescadero where the rooms remained empty and, perhaps haunted, for decades.

In 1992 I published “The Coburn Mystery”, acknowledged as a definitive history of Pescadero. Regrettably, instead of the critics focussing on the history of Pescadero, they fell into the quagmire of environmental politics. The book covers all aspects of Pescadero’s fascinating history and should be read. “The Coburn Mystery” is still available and can be purchased at Ano Nuevo State Reserve.

Half Moon Bay’s City Hall Has Small Town Charm

R.I.Knapp/Half Moon Bay’s Inventive Genius

R.I. Knapp, Photo San Mateo County History Museum, Redwood City

R.I. Knapp, Photo San Mateo County History Museum, Redwood City

Legend has it that in the 1870s when the inventive genius Robert Israel (“R.I.”) Knapp moved to the close-knit Coastside, Half Moon Bay had more watering holes than anything else–and saloons were often built next door to the blacksmith’s shop.

By trade, “R.I” was a top-notch blacksmith–but he never stepped inside a saloon. He was a religious man who must have agonized that Half Moon Bay had more saloons than churches. Knapp was a teetoaler who, in addition to his blacksmithing duties, spent his time trying to figure out how to fix things and to make them work more efficiently. Wagons. Carriages. Farming tools.

Knapp knew that Half Moon Bay marked the entrance to the Coastside, and that the rural village held great potential for new business but the place failed to impress outsiders. One traveler said that Half Moon Bay “contains little to attract a stranger,” and an unsympathetic stagecoach passenger observed that he saw “mostly whisky and blacksmiths”.

But in the 1870s, with the United States Geological Survey team preparing reports on California’s abundant natural resources, and the transcontinential railroad connecting the coasts, it was the beginning of an exciting era. There was even talk of a railroad coming to the Coastside, opening up this isolated and beautiful part of the world.

In Half Moon Bay new businesses were opening up– a brewery, hotel and retail stores, including a millinery shop. Local sawmill owners provided lumber for the burgeoning town, and the farmers harvested potatoes and other vegetables, winning blue ribbons for giant heads of lettuce and five-foot-long cucumbers grown in the rich, loamy soil.

Knapp’s repair shop was the hub where the locals gossiped about the booming Coastside and the regulars grew weary of hearing R.I. complain that there were too many saloons.

(Photo :Inside a blacksmith’s shop in Half Moon Bay, Spanishtown Historical Society.)

(Photo :Inside a blacksmith’s shop in Half Moon Bay, Spanishtown Historical Society.)

Of concern to the farmers was the Killgore Plow, the only tool available for use on the Coastside’s hilly terrain. They said the plow wasn’t versatile–anything would be an improvement.They complained that “the Easterners”, who manufactured the cursed Killgore Plow, knew nothing about the mountainous coastal terrain. Could R.I. Knapp build a plow to suit their needs?

Knapp tackled the project with passion, coming up with a simple locking device that enable his new lightweight, but sturdy plow to swivel, distributing soil to the right or left, as desired. The new plow, invented in Half Moon Bay, answered every Coastside farmer’s prayer.

A major technological breakthrough, Knapp’s “Side-Hill Plow” increased agricultural productivity and received a patent in 1875. But Knapp didn’t anticipate the plow’s enormous success and he found himself unprepared for the flood of orders that came. He converted his repair shop into a small factory and the first steel plows were fashioned entirely by hand with the steel cut on an anvil. But the orders kept pouring in and it became clear that Knapp better install better labor-saving equipment.

Those who witnessed Knapp’s innovation described with wonder the single-horse on a treadmill powering the machinery. But even this “one-horsepower” machine could not meet the demand for more and more plows as Knapp’s employees worked late into the night to cut into the mountain of orders.

Events would soon severely test Knapp’s spirit. The celebration of New Years 1880 had barely faded from memory when a mass of flames engulfed Knapp’s factory, spreading to Quinlan’s Saloon and burning a stagecoach owned by Taft & Garretson.

Lacking modern day fire-fighting equipment, efforts were made to save Knapp’s uninsured building by pouring water and using blankets to smother the burning structure. To establish a firewall, all the nearby fencing, sheds and barns were hastily torn down, but the conflagration consumed everything in its path.

Knapp suffered heavy losses but managed to save some of his tools and steel. Never taking time to mourn his fate by sifting through the ashes–and ever the passionate inventor–he immersed himself in the design of a two-wheeled cart reportedly “as easy to ride as any four-wheeled buggy”. As locals strolled along Main Street they were delighted to see Knapp’s cart on its maiden test run.

(Knapp’s two-wheeled cart. Photo Rosina Gianocca)

A month or so later, the then 47-year-old R.I. Knapp started all over again, moving his side-hill plow business into a new building on Main Street in Half Moon Bay. He said he was ready to take new orders.

Honors showered upon R.I. Knapp, the Coastside’s famous inventor, the man responsible for a new business that employed members of several families in town. San Francisco’s prestigious Mechanic’s Institute awarded him their silver-and-bronze medal. Knapp won further distinction by representing Half Moon Bay at the World Exposition held in New Orleans in 1885.

But there was a danger in the success of his Side-Hill Plow. Knapp’s patents were running out, and there were rumors that the big name farm equipment makers such as John Deere and South Bend Chilled Plow Company had been working on an identical plow design.

By the time Knapp’s son, Horace, had joined the enterprise, things had come a long way. The company produced a glossy catalogue offering an array of plows for different types of terrain. “Graders Pride No. 4” was used to cut grades for the Coastside’s Ocean Shore Railroad and the “Hula Queen Reversible Plow” was designed to till the fields in the Hawaiian Islands.

Predictably, R. I. ‘s plow patents began to run out and manufacturers such as John Deere rushed to copy them, selling the identical machinery at lower prices.

Three years after the 71-year-old Robert Knapp passed away in Half Moon Bay in 1904 , his heirs moved the plow factory to San Jose where the fruit orchard business promised a new need for agricultural equipment. Feeling over-confident, Knapp’s son, Horace, prepared for business demand on a grand scale. He constructed an expensive new factory and built the first orchard tractor. But he was unable to compete with the companies that could produce the same farming equipment faster and cheaper, and the inventive Knapp family closed their doors forever in the 1920s.

Photo: R.I. Knapp’s house on Johnston St., Half Moon Bay.

Photo: R.I. Knapp’s house on Johnston St., Half Moon Bay.

.

Me & Ken Kesey

I never knew Ken Kesey personally but one of the first books my father gave me was “One Flew Over the Cukoo’s Nest”

“Cukoo’s Nest” made such a deep impression on me, and when I discovered that he lived in woodsy, isolated La Honda, and I saw the cabin he lived in, I felt very close to this author I so admired.

It was the 60’s–almost “romantic” now–remember Kesey’s day glo spray painted bus (now in the Smithsonian museum, driven there by Kesey himself a few years before passed) and the Merry Pranksters.

The folks in La Honda did not appreciate Kesey choosing their neck of the redwoods to live and write and play in. Legend has it that on more than one occasion Kesey walked to his mailbox outside to find bullet holes in it.

And of course Ken Kesey had his share of legal problems–I’ll try to get into a more detailed bio of the famous author in a future post because his past directly relates to the writing of that great book, “Cukoo’s Nest”.

Ron Duarte of Duartes Tavern in Pescadero, Ron’s Aunt Carrie, now gone, once told me Ken Kesey came down from the mountains to take out books at the local library. She was the librarian, she would get to know everybody who took out books.

When I was on the San Mateo County Historical Museum’s Board of Directors some years ago, I wrote Ken Kesey and asked him if he would contribute an article–or even a “fragment” to our historical publication, “La Peninsula”. I typed the letter on a typewriter, I think, and mailed it to his farm in Oregon. He had moved there from La Honda. I’m sure life there was more peaceful.

Was I surprised when I received an answer from Ken Kesey. I must have been jumping up and down–he had used my typed letter to create a work of art with his magic marker pens.

Here’s Kesey’s response to my request that he pen “something” for the county’s historical journal.

(Imposed over my letter Kesey’s colorful magic marker words read: “La Honda is a slingshot at the sky!”)

(Imposed over my letter Kesey’s colorful magic marker words read: “La Honda is a slingshot at the sky!”)

When Ken Kesey was delivering the historic day-glowed magic bus to the Smithsonian in D.C., he stopped off in San Francisco at a book fair and I almost talked to him but he was in motion, moving here, moving there, physically, a small man, but he was a muscular ball of energy.

I never knew Kesey personally but I will never let go of my old copy of “Cukoo’s Nest”, both a reminder of the culture-changing 1960s and of a great book filled with truths that will remain relevant forever.

Murder in Montara: Part II

In the summer of 1946 the bodies of two dead children, 7 months and about two-years-old, were discovered partly buried beneath a blanket of leaves in remote Wagner Canyon in Montara. The children’s mother, 21-year-old Lorraine Newton, was found a few feet away, shoeless and stumbling about in a daze, her skull fractured from a blunt instrument, perhaps a hammer or tire iron.

The lone survivor of this vicious crime, police brought Lorraine to the Community Hospital in Half Moon Bay where, under the care of Colonel Harold Roycroft, she sank into and out of consciousness, sometimes calling for her daughters, Barbara and Carolina Lee. Few questions were permitted (and she was not told the little girls were dead) but investigators learned that she was an Alameda resident and that a day earlier she, her husband, Vorhas, and the kids, sat in their car and watched the waves at scenic Rockaway Beach in Pacifica. She recalled little else–or the authorities weren’t making anything else public.

Colonel Roycroft said Lorraine had a 50-50 chance of making it. He said the wound that caved in her skull appeared to have resulted from the same weapon used to kill the children.

But John Kyne, the Coastsider who found Lorraine Newton, saw what he believed was the suspect’s car and that gave investigators good information on go on. That car, authorities learned, had been borrowed from Vorhas’s sister and returned.

“So far, we have found nothing to establish a motive for the murder,” Sheriff Walter Moore told the media which dubbed the heinous crime “The Babes in the Woods” case. “It appears that [Vorhas] Newton may have suddenly gone berserk during the family ride.”

In the East Bay, where the Newtons resided in Alameda, Frank Marlowe, the County D.A.’s investigator was talking to neighbors about Lorraine and Vorhas. They were unanimous in their impression of the Newtons as a nice couple. Vorhas was “modest and mild-mannered”, an amateur wrestler.

Newton’s brother, Ben, who lived in San Francisco, described his brother and sister-in-law as happily married, with Vorhas the “perfect husband” He worked as a glazier for the W.P. Fuller Company in South San Francisco and had worked for the Coast Guard until six months earlier.

But where was Vorhas Newton? Nobody seemed to know.

He didn’t have a car and police were looking for him at railroad and bus stations. There were sightings of him from Redwood City to Marysville but nothing panned out.

In the Esst Bay Investigator Frank Marlowe learned that Vorhas had returned to the couple’s Alameda apartment where the Newtons had lived for three or four months. In the neat and clean apartment, Vorhas changed his clothes, and before leaving again, placed one of his wife’s dress on the bed and put baby bottles on the ktichen table.

More details dribbled out. The killer had removed all identification from the scene of the crime, including labels from the clothing of the children such as the red checked gingham dress the two-year-old had been wearing. Lorraine didn’t know what had happened to her wedding ring, it was not on her finger.

Meanwhile Lorraine’s parents, the Tuttles of North Hollywood, flew into Mills Field to be by the bedside of their beloved daughter.

….To Be Continued

Bonzagni Lodge

Postal Order Model

Incident at Billy Grosskurth’s Hotel: Part III

On New Years Eve 1934 the superrich, eccentric George Whittell slipped into his chauffeur-driven automobile and began the bumpy ride from his Woodside estate, where at least one lion roamed about, and headed over a squiqqly road to the Coastside, to the Marine View Tavern in Moss Beach, and its host, Billy Grosskurth, the man with a showbiz past.

Since the end of prohibition business had grown quiet at both the Marine View and its neighbor, Franks, a llively roadhouse which had been built six years earlier. At the peak of prohibition, in the late 1920s, politicians and silent film stars wandered back and forth, between Billy’s hotel and the newer place next door.

The final minutes of 1934 were ticking away when George Whittell pulled up in front of Billy’s three-story hotel overlooking the Pacific. We can only imagine how shocked and stunned witnesses were when the elegantly dressed millionaire got out of the car with a lion cub on a leash–it was as though he were walking his pet dog.

I don’t know what brought George Whittell to Billy’s hotel. Maybe it was on a whim, to celebrate the closing of the old year in Moss Beach. What they talked about I haven’t a clue.

Charles P. Tammany, Whittell’s chauffeur, said that Billy invited Whittell and the adorable five month old pet lion into the hotel. Against the advise of Whittell, added the chauffeur, Billy began to play and tease the lion. The lion was so cuddly cute, but at that moment it wasn’t feeling playful–and started to maul poor Billy. Or so he said in the lawsuit that followed.

“It was a wild African lion of vicious and irascible nature,” testified Billy Grosskurth.

“It was a friendly gentle little lion kitten of kind and amiable temperament,” countered George Whittell.

For the terror and mauling he suffered, Billy sued the Woodside millionaire for $250,000. He added that Whittell was of a depraved and vicious character and delighted in the animal’s attack.

But Billy was no match for George. Whittell, playing a game he was long familiar with, responded that he was a Nevada resident which may have technically protected him from Californian litigation at the time– (remember, Whittell had built the spectacular Thunderbird Lodge at Lake Tahoe, on the Nevada side, which I have visited, and can assure the reader of its uniqueness, in particular, the underground tunnel where Bill, the lion roamed freely, and where George, after a late night of drinking and gambling took his friends on a tour–).

A year later Billy Grosskurth’s lawsuit was dismissed.

As for the Marine View Tavern, the glory of what it had been during Prohibition continued to fade but Billy refused to sell the property. By the 1950s the building was decaying–and Billy became a familiar sight on the porch, playing solitaire and reminiscing about the past.

During the summer of 1958 there was a fire in Moss Beach and the Marine View Tavern hotel was torn down. The hotel had been Billy’s life and a year later he died at age 75.