Owen Bryant: Our “Beetle Man” in Montara, Part II

At the California Academy of Sciences, amateur entomologist Owen Bryant met Dr. Blaisdell, a Stanford doctor and insect expert who named some of Bryantâs beetles. Owen also befriended Hugh B. Leech, the Associate Curator of Entomology, and the man who would write Bryantâs obituary in 1958.

These were the experts who attracted the beetleman Owen Bryant and the reason he moved into the old Montara schoolhouseâso he could live close to the Academy located in Golden Gate Park.

When Owen and Lucy Bryant moved to Montara, lthey also purchased two building lots in the El Granada Highlands. Owen believed they might have oil beneath them as he had seen oil operations nearby. At any rate he had a special understanding of the petroleum business.

Dr. Ross suggested that oil was the source of Owenâs income. He was the president of the Calgary, Alberta-based Bryant Oil Company, and, while not rich, income from the venture sustained his lifestyle, enabling him to pursue his bug interests.

âHe had a dictatorial father,â? Ross told me four years ago. âI believe his father wanted to send poor Owenâwho was basically a bug collectorâto school to become a doctor.â?

Owen Bryant, who was born in Brookline, Mass. In 1882, attended Harvard, but according to his correspondence stored at the Academy, he did poorly in English courses, failing four times. He repeated the class until the sympathetic instructor passed him so that he could enter medical school as his father wished. He graduated from Harved in 1904 and spent three unhappy years attending medical school.

As soon as summer break came, the naturalist in Owen prevailed, and he was off to the Bahamas, Newfoundland, Labrador and Java collecting birds, mammals, reptiles, seashellsâand his beloved insects.

Then, in 1908, Owenâs father died and he was free, and that meant the end of his medical career.

Clearly Owen had enough income to become a gentleman collector. But he was scarred by the frustration of being forced into the medical education he did not want and the trauma of the failed English classes.

In 1939, in response to an âanniversary surveyâ? from Harvard College, an angry Owen responded:

âI have made it my business to avoid business and professional relations of each and every sort,â? he wrote, âbut have had the misfortune to be n ot quite able to keep out of the clutches of the legal and medical professions.â?

In discussing his lifelong commitment to observing insects, he sarcastically wrote: âMy hobby is the same one I have been engaged in most of my time for the last sixteen years, the puerile one of catching bugs, presumably begun then because I entered my âsecond childhoodâ at that time.â?

When reporting public service activities, Owen ridiculed the question by snipping that he had âtrapped one pack rat and four mice.â?

These were the words of an embittered man.

But the years smoothed Owenâs rough edges. In 1954, now living in Montara, he was again asked to respond to another Harvard College survey. This time Owenâs anger was gone. He matter-of-factly cataloged his affiliations and accomplishments, dryly observing that he was âstill at itâ?, that is collecting his insects.

The passage of time and Owenâs pleasant relationship with the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco were surely responsible for his mellowingâbut he never recovered from the trauma of flunking English classes at Harvard. That horrid experience blocked Owen from ever becoming a bona fide scientist. He believed he could not write well enough to author the all-important papers that were required.

For his entire life as a collector, he never could do the writing himself. It was always up to others. Someone had to correct his grammar and someone had to do the typing and someone had to address the letters to the appropriate person. The problem was solved when he married Lucy McBride in 1932. She was a competent secretary who helped her husband deal with all of his deficiencies.

Owen and Lucy were a good match.

Photo:  Lucy McBride Bryant, Special Collections/California Academy of Sciences

Lucy McBride Bryant, Special Collections/California Academy of Sciences

In his correspondence, Owen recounted that wife Lucy was a scrapper. He told of one incident when she faced up to water officials in Montara, claiming that the Bryants were not getting their proper amount of water. In spite of the bureaucracy, she prevailed.

In 1957, Lucy McBride died. Her death hit Owen very hard and he became morose. He gave a treasured insect storage case to Paul Arnaud, an acquaintance from Redwood City. The old Owen would never have parted with his equipment but it was clear that even his precious bugs could no longer hold his interest.

On October 26, 1958, the 76-year-old amateur entomologist Owen Bryant passed on. He left his entire estate to the California Academy of Sciences in Golden Gate Park. The estate included the Montara Grammar School, the El Granada Highlands building lots, boxes of correspondence, photosâand, of course, his beloved insect collection.

(The property was sold but the correspondence, photos and insects remain as part of the California Academy of Scienceâs collection).

Dr. Ross recalls revisiting the Montara schoolhouse shortly after Owen Bryantâs death. He was very moved when he saw Owenâs family photographs strewn across the cover of the king-size bed in the bedroom/classroom.

Perhaps Owen Bryant had been studying those photos, reviewing his own life.

âThe Bryants were gypsies of a sort,â? Dr. Ross reflected. âBoth liked that life and they would not have lived long in that schoolhouse. One day they would have gotten itchy feet, and said, âLetâs go to Costa Rica. The insects are good down there.â?

Owen Bryant: Our “Beetle Man” in Montara, Part I

At left: Owen Bryant (Special Collections/California Academy of Sciences)

At left: Owen Bryant (Special Collections/California Academy of Sciences)

In an earlier post I wrote a tribute to Richard Schellen, the wonderful Redwood City librarian, now gone, not only makes researching Coastside history fun â- sometimes he turns it into one of those special âEureka!â? moments.

A while back, I had one of those lucky experiences.

While flipping through the Schellen Collection, I was zeroing in on Montara, when I became fascinated with a 1958 obituary. The subject was Owen Bryant, an amateur entomologist, who resided with wife, Lucy, and their collection of 200,000 mounted insects in Montaraâs historic two-story schoolhouse.

Wow! A bug collector in the old grammar school? I had to know more.

This is how it worked: The Schellen Collection steered me to the original newspaper article with the complete obit– and the Eureka! I needed to further my research: Owen Bryant had nurtured a close relationship with the California Academy of Sciences in San Franciscoâs Golden Gate Park.

A phone call later, I learned that the Academy of Sciences had it all.

Four years ago, on a rainy winter afternoon, I sat in the curatorâs offices, looking through several boxes of Owen Bryant biographical info. I also met Dr. Edward S. Ross, then the 86-year-old curator-emeritus of entomology. He had been with the Academy since 1939, an expert in 300,000 species of insects, but he was even more famous as a âclose-upâ? photographer. The walls of his office were covered with the extraordinary pictures of people, places and wildlife that had been published in college textbooks and National Geographic.

In the early 1950s, Dr. Ross visited the Bryants at Montara, followed by dinner âat the restaurant (Frankâs) on the nearby beachâ?. Ross clearly remembered seeing the bell towers of the two-story Montara Grammar School from Highway 1.

Ross remarked that the 60-x90-foot former schoolhouse had been converted into an unusual residence. On the first floor Owen and Lucy used a classroom as a bedroomâpushing their king-size bed up against the blackboard. One of the few things that brightened the surroundings was a museum quality of Mt. Resplendent in the Canadian Rockies. There were many boxes yet to be unpacked, including some containing Lucyâs inherited silver.

None of Owenâs prized insects could be seen on the first floorâalthough upstairs there was a âbug roomâ?, office and library shelves overflowing with naturalistâs books bounds in fine Moroccan leather and gold tooling.

Photo at left: During the 1950s Montara Schoolhouse was home to the Bryants.

Photo at left: During the 1950s Montara Schoolhouse was home to the Bryants.

Did the reclusive Owen and his vivacious wife, Lucy, find Montara dullâinsect-wise? They had just come from a favorite bug-hunting area on the outskirts of Tucson, Arizona. Insect collecting was outstanding there at the base of the Santa Catalina Mountainsâespecially during Arizonaâs rainy âmonsoonâ? season when there was a great burst of life in the desert at night. The wind was soft, the flowers were fragrant and it was âgangbustersâ? for beetle hunters. Owen, wearing bug-collecting gear, and armed with a stick, beat the bushes, overturning stones to unearth his prized insects.

âOwen had a great time in Arizona,â? Dr. Ross told me. âFrom moment to moment he didnât know what kind of beetle was going to bounce in. It was like manna from heaven. Most people would say, âUgh!â Owen Bryant said, âAhh!â?

Before settling down in Montara, Owen hadnât stayed put for very long. He and Lucy were rootless, always moving from one place to the next: Alaska, Banff, Canada, Steamboat Springs, If anyone wanted to locate the Bryants, all they had to do was find out where the beetles were flourishing and Owen and Lucy would be there.

Dr. Ross said that Owen Bryant had moved to Montara âto be near the Academy. He came up here once a week with boxes of things.â?

Owen needed the experts at the Academy of Sciences to identify his insect specimens. Sometimes he brought in a beetle that had never been seen before and the scientists named it.

Beetles were Owenâs greatest interest and by 1950 he had donated 38, 530 specimens. Ross pointed out that many accomplished people were amateur collectors of insects. Charles Darwin, for example, was fascinated with beetles because of their tremendous diversity.

At the Academy Owen Bryant found more than expert entomologists; he forged enduring relationships with the scientists and the institution.

Dr. Edward Van Dyke, who had been there since the early 1900s âwas a famous beetle person,â? Ross said, âan M.D. who practiced medicine but his real passion was the bug collection he kept in the back office. Whenever the patients werenât around, Van Dyke was in the back room.â?

â¦To Be Continued

Thank you, Richard Schellen

Years ago, when I first started searching through old newspapers for stories on the Coastside, a helpful librarian steered me to the “amazing” Richard Schellen Collection.

I cannot praise Richard Schellen enough for the work that he left anyone interested in local history, or a specific event, such as when a building was built or burned.

Mr. Richard Schellen was once Redwood City’s head librarian, but I think of him as a librarian’s librarian.

This wonderful man organized and typed up thousands of stories– either in their entirety or the first few sentences, (you could always find the longer original) –and he organized these stories by date and town, in some cases going back to the mid-19th century and earlier.

In the Schellen Collection you can find political stories, business stories—murder stories….Perfectly organized by town and date. It’s a great resource.

I wish I could have met Richard Schellen to thank him personally. He gave us writers and historians and the folks of San Mateo County so much.

The Schellen Collection can be viewed at the main Redwood City library as well as the San Mateo County History Museum, located in Redwood City’s old courthouse.

Here’s hoping you enjoy the collection as much as I did.

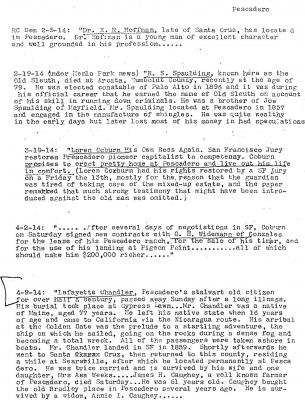

A sample page from the Richard Schellen Collection–this sheet lists a few stories about Pescadero. Click to enlarge.

A sample page from the Richard Schellen Collection–this sheet lists a few stories about Pescadero. Click to enlarge.

Murder in Montara: Babes in the Woods Case 1946: Part VI

Photo, at right: The preliminary hearing for Vorhes Newton was held at the old Half Moon Bay High School.

Photo, at right: The preliminary hearing for Vorhes Newton was held at the old Half Moon Bay High School.

There was so much interest in the 1946 âBabes in the Woodsâ? case that the arraignment of the 24-year-old âconfessedâ? murderer Vorhes Newton had to be moved from Half Moon Bay Judge Bettencourtâs intimate courtroom to the much larger school gymnasium.

The schoolâs gym could accommodate the 65 officials, attorneys, family members, press and news photographers gathered for the brief proceedings. Children were kept out but you could see their curious little faces pressed against the windows of the building.

A dozen members of the defendantâs family sat behind Vorhes, whose hunched shoulders gave him a fragile bearing. The black eye he sustained in an accidental fall at Lake Tahoe, where he was apprehended, was now turning a sickly green and yellow.

When he turned to look at his mother, she pressed her sonâs hand meaningfully, her eyes brimming with tears.

Vorhes Newton was accused of brutally murdering his two daughters, more babies, than children. He was also accused of attempting to murder his wife, and the mother of his children.

To record the seriousness of the moment, photographers, six of them, moved adroitly about the room, the searing white light from their flash bulbs creating a photographic memory in the newspapers.

Vorhes Newtonâs brief appearance at the first legal proceeding consisted of a few questions and then it was over and sheriffâs deputies drove the defendant back to the county jail at Redwood City.

A few days later Newton attended a more significant legal event, the inquest into the death of his two small girls discovered in a remote part of Montara on the San Mateo County Coastside. Their traumatized mother, Lorraine, survived the vicious attack but was still recovering from serious injuries in a Half Moon Bay hospital.

Sheriffâs deputies escorted their prisoner, attired in tan slacks and a jacket, his black eye completely healed, from the jail to a nearby mortuary chapel where a jury convened to hear testimonyâwhich turned out to be more grisly details of the killings.

Witness Jimmie Fideler, a Montara rancher, testified that he saw Vorhesâs wife. âShe had a black eye and was staggering. She had blood over her blouse,â? Fideler said, âand appeared to have been badly beaten. She told me she had been wandering all night on the road.â?

Fideler said that well known Coastsider John Kyne was with him. Kyne told the jury, âAll of us knew about the car going up the road the afternoon before, with a woman screaming, so we were on the alert that morning.â?

Kyne was talking about the car driven by Vorhes Newton, with his wife and children as passengers.

Upon advice of counsel, Newton himself refused to testify. The support he had from his family was evident again: when he returned to the jail he was accompanied by his sister and her husband, the same sister he had borrowed the car from for the tragic ride from the East Bay to the Coastside.

Following the testimony, the coronerâs jury– three men and three women, described as housewives–found that Barbara Ann Newton, 23 months old and Caroline Lee Newton, seven months, âcame to their death from skull fractures caused by blows with a blunt instrument wielded by person or persons unknown.â? They recommended further investigation by the district attorney.

Lorraine Newton was recovering from a skull fracture at Community Hospital in Half Moon Bay and did not attend any of the early proceedings. It was said that she didnât know what had happened to her children. Her parents, the Frank Tuttles of North Hollywood, wanted to be the ones to break the horrific news to their daughter.

But Dr. Raycroft, the head of the hospital, convinced them it was his role to his patient âat the proper timeâ?. That meant without the authorities presentâand he would not allow Lorraine to see her husband.

Two weeks after her children had been murdered, and during the preliminary hearing in Half Moon Bay, Lorraine Newton, still hospitalized, spoke publicly, âtestifiyingâ? for the first time. Besides her parents, County Investigator Frank Marlowe, Deputy Sheriff Jack OâBrien stood at her bedside as Stenographer Virginia Knight recorded the emotionally charged evidence.

It was almost unbearable to hear Lorraine speak, her voice breaking frequently, moving forward through heavy sobbing only haltingly.

She said she woke up battered and bleedingwith daughter Barbara dead in her arms. While stumbling she fell into a creek, and wet and shivering, she found an abandoned chicken shed before losing consciousness.

Then Lorraine Newton cried so hard that the testimony had to be stopped so she could regain her âcomposureâ?..

She denied seeking an abortion but said she intended to visit a doctor in San Francisco. What the purpose of that medical visit was we donât know. Again she recalled part of the fatal automobile ride, watching the waves at Rockaway Beach in Pacifica– and then remembering nothing until she woke up with her dead child in her arms.

Lorraine recalled that she and Vorhes didnât argue but that he was moody at Rockaway Beach. âWhen I last saw him,â? she said, â he was sitting in the car. Then I remember nothing until I woke up lying over my babyâs body.â?

Meanwhile, at the preliminary hearing held at Half Moon Bay High School, Assistant District Attorney Fred Wycoff questioned a dozen witnesses, establishing the facts of death, the murder ride, the discovery of Mrs. Newton and the children, the capture of Vorhes at Lake Tahoe and the finding of his wifeâs rings in his pockets.

Wycoff produced a witness, a Mexican farm worker, who testified seeing the man who drive into the canyon at Montara with a woman, and later emerge without her.

âInsufficient evidence,â? countered the famous defense attorney Leo Friedman, moving for dismissal.

There was the obligatory moment of silence– and then Judge Manuel Bettencourt ruled that Vorhes Newton be bound over for trial.

Outside the courtroom, Newtonâs attorney Leo Friedman courted reporters, verifying that Newtonâs neighbors said Lorraine was the quarrelsome half of the couple. He said that John Kyne discovered Lorraineâs rings were gone. When found, she was wearing a glove and Kyne helped her remove it to reveal the missing rings.

Could that mean Vorhes Newton ripped the glove off his wifeâs hand and took the rings, âDid he put her gloves back on her?â? Friedman asked reporters.

Six months passed before the trial would begin.

…To be continued…

Ocean Shore Railroad Model

The Hwy 1 Era

Three decades after the Ocean Shore Railroad declared bankruptcy and pulled out of the Coastside, the train’s right-of-way was paved over with a new road, eventually called Hwy 1. The paving occured in stages up and down the Coastisde, between the 1940s and 50s.

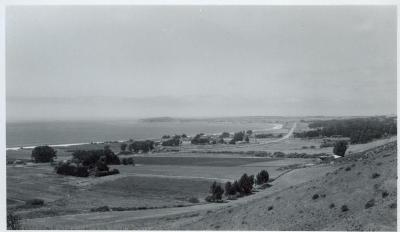

This R. Guy Smith photo could have been taken in the early 1950s–when development was taking place on “the other side of the hill” but not on the Coastside, still wide open. In this picture it seems the Ocean Shore left us little to remember it with. But if you look closely some landmarks are visible such as the old Amesport Pier (1860s, rebuilt 1916) at Miramar. That’s Pillar Point to the north.

Notice there’s no traffic? What’d they do, close the highway so the photographer, R. Guy Smith, could get the shot? Nice.

El Granada Vignette

(At below,right) About 1908, the Ocean Shore Railroad (smoky, isn’t it?) delivers and picks up well-dressed pasengers at an El Granada train station.

(At below, left) The Ocean Shore ignites a “land boom” in El Granada, and, where once artichokes grew, street signs appear–but no sidewalks or houses–yet.

(At below, left) The Ocean Shore ignites a “land boom” in El Granada, and, where once artichokes grew, street signs appear–but no sidewalks or houses–yet.

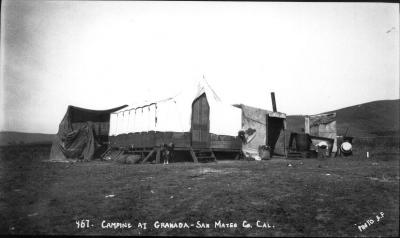

While waiting for houses, summer and all-year-round to be built, new lot owners camped out in tents like the one below at El Granada:

It didn’t happen….

1979 Interview with Pete Douglas/Bach Dancing & Dynamite Society

I always enjoyed interviewing Miramar Beach’s impresario, Pete Douglas, because he’s a one-of-a-kind, accessible, and always more than honest. You WOULD NOT believe the big names that have played at Douglas’s Bach Dancing & Dynamite Society.

Some of you will read Pete’s words and “hear” exactly what he sounded like, talking with the ubiquitious pipe in his mouth, then pausing to laugh at what he said, then perhaps musing on some other internal revelation causing him to laugh again and conclude, “so that’s what that was all about”. Maybe he was solving the puzzles of his life while he talked. And Pete, who came from southern to northern California, loves to talk.

We were upstairs in Pete’s office at the Bach Dancing & Dynamite Society overlooking the Pacific Ocean in Miramar. His office, a desk and chair, was located in the big, spacious upstairs next door to the room where the jazz and classical concerts take place.

Here’s the beginning of the 1979 interview.

Pete: I was a bohemian of the 1950s, in college and after, anti-establishment, yetthere was the other straight side of me. I had a family and I had to get a job and I took a job in this county as an adult probation officer….It’s not like a regular job but it’s an official police sort of job which me very suspect with the hardcore beats that used to come through here.

June: What did being beatnik mean in the 50s?

Pete: A lot of good stuff out on that. The beatniks were a real extension of the American bohemia right on from the turn of the century, the 20s, the 30s, 40s and 50s. It was just another twist or continuation –however, the style it took was anti-establishment, anti-materialistic America. They had intellectual leaders like Sarte, the French writer, and the San Francisco poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti.

We are interrupted as the phone rings.

Pete: Douglas speaking. Yeah. Every Sunday. This Sunday is the guitarist Charlie Byrd. And then following that is Coke Escovido 13-piece Latin Jazz Orchestra. Yeah, we’re hardcore jazz, although we do a greater variety of it, like traditional, swing, bop, mainstream, progressive, spacey, funk, Latin. Yeah, I’ll mail you something right now, and if you want ot remain on the mailing list it’s $3.00 a year. What’s your name? Carder? Oakland? Tremendous this fall. We’ve got a blues thing, Sunnyland Slim and Eddie Clean Head Vincent on the 9th, David Fathead Newman on the 16th, Zoots Sims….We’ve been doing this for 14 years. Every Sunday. That’s the only time we do it. Right on the beach. Beautiful small roomm for jazz. Bring your own juice. Okay.

Pete hangs up the phone and he’s back into the interview with me.

June: Would you say the Bach has some of the finest jazz music in the world?

Pete: Now I could say yes. We have the best instrumentalists in non-classical music, which tends to be jazz oriented but not all of it is hardcore jazz.

June: Is it the only jazz house of its kind in northern California?

Pete: Kummbwa Jazz Center in Santa Cruz –they incorporated as a non-profit music organization and they do primarily jazz once or twice a week. And they followed our pattern. That’s the only other non-profit I know of.

June: And you’ve always had a fascination with the beach ever since you were down at Hermosa and the Lighthouse? Where does that fascination come from?

Pete: Some people like the beach, the whole space. Beach communities are liberal, live and let live, more tolerant, and, of course in Southern California there’s a lot of action on the beach whether it be jazz or other things. Going back to the 20s and 30s big dance halls were all on the beach, amusement parks, that kind of thing. That’s the only place I felt a sense of freedom, on the beach as opposed to the conventional residental setting.

June: You say you lived like a beatnik. What does that mean?

Pete: Well, the beatnik style of dress was merely any odd collection of clothing that you pick up for very little money. …In other words to exist without the conventional jobs, to exist without the 9-5 jobs–the freedom to deal with your interest in arts and crafts….Jazz has always been associated with and still is the minority music, a protest music, an unconventional music as opposed to our European musical traditions.

June: I’ve noticed that you’ve changed your attire from what you used to wear.

Pete: The only thing that’s changed is that I used to wear sneakers, ratty old sneakers….I’ve been wearing Levis since I was 11-years-old. And in Los Angeles on the beach it was Levis and Levis have only changed to the extent that they’re slightly flared with a belt. Prior to the Mod scene of the 60s, it was not cool to wear a belt. In my case I’ve had these old captain’s hats and I also wear a turtleneck because they’re comfortable when it’s cool.

June: Didn’t you want to run your own espresso house?

Pete: Oh, yeah. Even in Santa Barbara, before I got out of college. Oh, by the way, being a graduate of college was not exactly in the beat tradition. They were drop-outs. But I was a dual person coming from–and this was not unlike the freaks of the 60’s–a lot of ’em were upper middle class kids who revolted against everything, and a lot of the beats were upper middle class kids. Some of em were just bums. Took on the appearances because it was fashionable. The beats had to survive with some kind of economic ‘mom and pop’ store. If they could figure out how to do it, live off the crumbs of society….

June: This little building downstairs–was it originally built in the 1940s?

Pete: I think it was built around 1947.

June: So before that there was nothing here?

Pete: No.

June: (Regarding the ‘little building’ downstairs) I remember you looked through the Police ‘blue sheets’. What did you find?

Pete: Felonious assault, burglary. See, it was run by Gladys Klingenberger and her husband, Carroll.

June: Do you think they’re still alive?

Pete: I think Carroll died and I just don’t think Gladys is around. I last saw her over ten years ago at the Miramar Hotel, (burned in the 1960s) at the bar, juiced, bad mouthing everybody as usual.

….To Be Continued