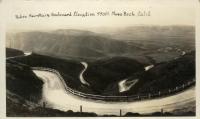

The old landmark I refer to in the headline above was an historic wharf at Miramar, partly destroyed by huge waves in early November 1928 or 77 years ago.

About 150 feet of the wharf at Miramar Beach had been swept away by heavy seas and a team of men worked feverishly to retrieve the floating wood and debris.

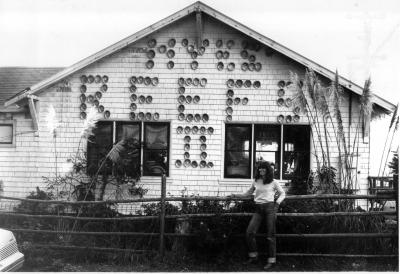

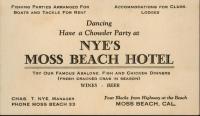

It was originally known as Amesport Landing ( built by Judge Josiah P. Ames in 1868)–and after it was modernized, it was called Miguel’s Wharf, named after the Half Moon Bay family who built the beautiful glass-windowed and redwood shingled hotel called the Palace Miramar.

The pier and the hotel, once the site of Amesport Landing and a warehouse and customs house.

The pier and the hotel, once the site of Amesport Landing and a warehouse and customs house.

The wharf’s fame grew out of the Amesport, pre-Ocean Shore Railroad era when Miramar was the center of a tiny seafaring village, with a warehouse for shipping and receiving freight for the Coastside. There was a waterfront saloon and a customs house from which passengers bound for San Francisco boarded the colorful steamers “Maggie” and “Gypsy”.

(Valladao is a well known name in Half Moon Bay, and one of their family members, “J.C.” worked as a clerk in the custom’s office.)

It was Moss Beach writer, Peter Kyne, who fell in love with Miramar and the steamer “Maggie”, so much that he featured them in his first book, “The Green Pea Pirates”. Local legend has it that when Peter was a kid he watched the steamers stopping along the Coastside to drop a package of nails here and pick up a letter there.

Hearing about the pretty hotel, the wharf, the steamers and the writer who loved it all, makes you believe all was perfect in Miramar.

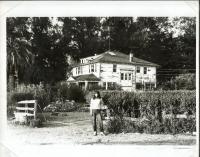

Nothing is ever perfect, and behind the facade was a longtime feud between the new hotel and wharf owners, the Miguels, and the Mullens, the former “power” at Miramar. The Mullens, whose lovely farmhouse still stands on the east side of Highway 1 in Miramar, had operated the Amesport Wharf until the landing lost its usefulness as a source of transportation and was plunged into bankruptcy.

Along came the Miguels with a well known architect’s plan for a beautiful hotel that would serve Ocean Shore Railroad passengers. The indoor salt water “plunge” and the restored wharf would knock the socks off visitors. It was inevitable that a confrontation would arise between the Mullens and the Miguels.

That story coming up soon!

photo by Suzanne Meek)

photo by Suzanne Meek)