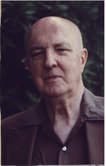

Story by Michaele Benedict

Piano Daddy

Once Robert Sheldon accidentally locked himself out of his house in San Francisco. He peered in the windows and his cats peered back at him.

“If you had had children instead of cats,” a friend told him, “there would have been someone to let you in.”

But in a sense, Mr. Sheldon had many children (just none at the house on Aptos Street that particular day) and I was one of them. The bond between music students and their teachers is sometimes our own homegrown guru-apostle situation and has been for a very long time. Piano teachers are so partial to their own students that they must excuse themselves from the juries of piano competitions if their students are playing. Musicians always cite their teachers in their biographies, but do not always name their natural parents. Some musicians even trace their musical genealogy, teacher, grand-teacher, great-grand-teacher.

Mr. Sheldon was my piano daddy. He was not concerned with feeding and clothing me as my natural father was, but he attended to my mental and professional growth for fourteen years. He pushed me to my musical limits, he expanded my horizons, and he provided me with a much-needed ongoing reality check.

I had already had years of piano lessons by the time I met Sheldon, so he was not concerned with teaching me to read music. Instead, he introduced me to the architecture of music, the background and foreground of the compositions I was trying to learn. It was no piece of cake, let me tell you.

If I arrived early for a lesson, I learned to park around the corner, out of sight, because Mr. Sheldon would come outside and get me, sometimes pausing to hose the dust off my car (Montara still had dirt roads in those days.) After the lessons, I would drive a block or so away, park, and take notes on the lesson before I forgot everything. Sometimes I was convinced that my lessons would be the death of me.

“Play it again. Now play it with the other hand. Play it hands together. No. Play it back to front. Play it up an octave. Play it down an octave. No, that will never do. Try again. Write the date on it. Here, finger every note. Try it again.”

His mild blue gaze seldom showed impatience or annoyance, but one felt that if he could stand all this noise, the least one could to was to keep trying. Sometimes I had to go home and take a nap after a lesson.

“I know you are having a hard time at home,” he once said, “but at least you turn it into something, music or poetry.” He would set my lyrics to music and ask for more. He would assign me a Chopin Polonaise so I could thrash the daylights out of the piano instead of going through emotional turmoil.

My natural father thought everything I did was just fine, so I could hardly believe him when it came to an objective view regarding my music. Sheldon had no such constraints. “Well, that’s the Mr. Magoo school of piano playing,” he would say,

“Grope around and hope for the best.”

Or “If there’s a hard way to do something, you’ll find it.”

Or, more encouragingly, “You will be a great teacher, because you have every problem you are likely to encounter in a student.”

“I may not always be kind,” Sheldon once said, “but I try always to be just.”

Sheldon’s was a holistic approach to music-making. It might involve lunch, if he thought you looked undernourished. If you seemed tired, a lesson might consist mostly of music history or even stories: “In this Bagatelle, I think of people who live on the west side of a tall mountain. They know morning has come, though it is still dark. There is no real dawn. Imagine the sheep bells, the sounds from the other side of the mountain. Then suddenly the sun clears the mountaintop in a blaze of light. That’s what Beethoven makes me think of here.”

Sheldon might accept payment for some lessons, (the Conservatory scolded him for not charging enough) but not for others. If you were preparing for a performance, he might insist you have a lesson every day, but he would not charge for the extra lessons. He once used a life insurance payout to send a student to England for further study. He only taught people he wanted to teach; we students would whisper about unfortunates who had been dismissed after a lesson or two.

Sheldon declined after Margaret, his wife of many years, passed away. He gave his car to a waiter at a nearby restaurant because the waiter “needed one.” He gave away his nine-foot grand piano. He asked his students what they wanted and put their names on the paintings, the books. He talked me into accepting a lovely Chippendale mirror along with the thing I really wanted, the bottle of Golliwogg perfume from Paris, 1906, (which inspired Debussy’s “Golliwogg’s Cakewalk”.)

What does a good father do, anyway, other than beget us? He goes first and shows us the way. He protects us, looks out for our welfare, provides a moral example, loves us, takes pride in our accomplishments and pleasure in our company. He teaches us how to get along in the world. When he leaves, the loss is made bearable by remembering everything he gave us.

(Michaele Benedict has written more about Robert Sheldon and his teacher, Egon Petri, athttp://www.pianoeu.com/petri.html.)

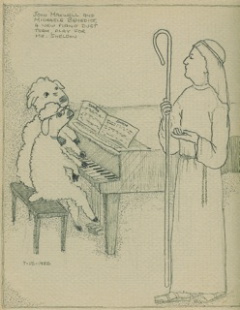

[Images of Robert Sheldon and a cartoon that reads: John Maxwell and Michaele Benedict, a new piano duet, play for Mr. Sheldon!}