Story by Angelo Misthos

Note: “Optimism does not a success make”–June quote

Created by June Morrall

Story by Angelo Misthos

Note: “Optimism does not a success make”–June quote

Story from John Vonderlin

Email John Ibenloudman@sbcglobal.net)

‘

|

Hi June,

It was stories like the following that helped to give Moss Beach its name. Resort owners were glad to make Moss Mania, Pebble Pathology, and Shell Sickness, all common ailments along the beaches of the Coastside in the 1800’s. Enjoy. John

LETTER FROM SANTA CRUZ. From the special correspondent of the Alta. Santa Cruz June 14th, 1867.

The Sea-Moss Mania.

The ladies down here have a perfect mania for gathering sea-moss. One lady has collected half a bushel of it, at least. There is something fascinating in the employment — the moss looks so pretty, dotting the beach; and it is interesting to search out the choice colors of it. As many ladies have never gathered moss, and do not understand how to prepare it for making up in wreaths, bouquets, etc., I will tell them how it is done. During high tide the moss is washed high on the beach, and can be gathered dry, though generally you find it in the greatest quantities on the wet beach, among the sea-weeds, as the waves wash them on shore; then, again, it is washed up in large bunches, separate from the weeds. Sometimes, in following up a receding wave, in pursuit of a bunch of moss, the water comes rolling back sooner than expected, and you find yourself immersed over shoe-tops. It is delightful, after feathering a basket full of moss, to walk to a little pond near by the beach, the water from the mosses dripping over you the while; then, to sit down on a rock by the pond, throw your moss in the water, wash it and then replace it in the basket, all nice and clean. You throw off your gloves to do this; the water is warm and pleasant; you will enjoy it; it will make your hands hard and red, and your face will get well browned up walking on the hot seashore. But, there is no pleasure in gathering sea-moss in gloves and veil. Next, you carry your mosses to the house, spread them out, when dried, lay them carefully away in boxes. When ready to arrange it, place a few pieces of it at a time in a basin of water, where the leaves will separate, and resume their natural size and form (they shrink very much in drying) but, in raising it from the water, the separate leaves of a stem fall together again, and to obviate this difficulty, slip a piece of tin, a plate, or card, whichever you wish to dry it on, in the water, under the moss, and in this way it can be raised in nearly its perfect shape. If you wish to let the moss remain on the card, press it, when partially dry, between the leaves of a book. When dried, it it easily removed from the card, or whatever it is dried on, and ready for arranging as you wish. May, l am told, is the most favorable time of the year for gathering it. The manner in which gentlemen gather moss is amusing. They spend considerable time collecting it — for their wives, I suppose, or perhaps for somebody else’s wives. At all event, they gather it, and they pick up sea-weeds, grass, shells, sand, sticks, and everything connected with the moss, indiscriminately.

Since writing the above, I have made a discovery. Sometimes, in removing moss from the paper on which it is dried, it sticks and breaks. To prevent this, oil the paper slightly. I believe, is considered the best thing to dry it on. Hagar

|

|

|

|

|

Story from John Vonderlin

Email John (benloudman@sbcglobal.net)

[ Note:The usual answer to this question is that it was easier to build on the other side of the hill, on the flatter land, in San Mateo, San Bruno, etc. There may be other reaasons; please let us know.]

PROMO FOR THE OCEAN SHORE RAILROAD

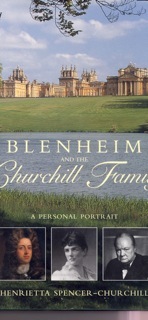

And that name was BLENHEIM. Not the most beautiful name, I have to admit. But the place Blenheim is a very beautiful home, and a home to an important political family.

I don’t know how serious the name change was; it was instigated by the famous Kyne family, well known farmers in Moss Beach who produced the well known mid-20th century author Peter Kyne. For the longest time, I couldn’t figure out the origins of BLENHEIM but the internet came to the rescue. Here’s a book called “Blenheim and the Churchill family.”

Blenheim, a magnificent palace was the birthplace of Sir Winston Churchill.

You can see that the Kynes thought of Blenheim as a joke, the name Blenheim, the fancy palace to replace that of Moss Beach, a farming community with a beach unlike any other. Actually, I’m not sure when Moss Beach became Moss Beach, if it was a name that the Ocean Shore Railroad gave this special place.”

The book is called: “BLENHEIM and the Churchhill Family: A Personal Portrait by Henrietta Spencer-Churchill”

For more information, please click here

Story from John Vonderlin

Email Jon

Email John (benloudman@sbcglobal.net)

Reply Reply |

Forward Forward |

Email Michaele: (mlbenedict@att.com]

Mystery with Strings

A Short Story by Michaele Benedict

Musical instruments have their own lives. Most of them outlast one generation, so they get passed down, passed along, get lost and found again, get put away in attics, get stolen, recovered, or offered at junk sales like the little violin which finally regained its voice recently in Montara.

It was a rather battered orange-painted instrument missing some essential parts, so it was impossible to know what it might sound like. A friend whose daughter plays violin had found and bought it, thinking it would be a shame for an instrument, even a battered instrument, to wind up among garage sale cast-offs.

Burned into the back of the violin were the words “Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, School District.” “I telephoned them,” the rescuer said, “and asked if they wanted it back, but they said they hadn’t had a string program for years, so they had no use for the violin.”

My cellist husband, who sometimes makes minor repairs on stringed instruments, heard about the discarded violin and asked if he could look it over for a while. Chipped varnish covered the maple and ebony. There were various scars and dings. But visible through the F-holes (the scrolled openings on the tops of stringed instruments) was a label which said “Antonio Curatoli, Mittenwald, Germany, 1928” and “Copy of Amati”.

“This might be a pretty good German violin,” Charles speculated.

I was curious about Antonio Curatoli and tried to research the mysterious luthier or instrument maker. The consensus among fiddle fanatics seemed to be that there may or may not have been an actual maker named Antonio Curatoli. He may have been a Neopolitan seller of violin strings who learned to make instruments. Or the name may more likely have been a trade name of the German violin company E. R. Schmidt, whose instruments were imported in the early 20th century by various companies including Sears. “Sort of like Betty Crocker,” Charles said.

The Curatoli violins sold for about 25 dollars in the 1920s, but they are bringing two or three thousand in these days of scarce fine wood and carbon fiber substitutes. The Philadelphia violin was, of course, virtually worthless as it was.

For several months, the violin sat in various places in our house, being scraped, sanded, and finally varnished with amber, a bit at a time. It perched, drying, on a kind of stand, where it was frequently examined (longingly, I thought) by the teenager whose father had found it.

This young woman applied for and received a scholarship from the Coastside Community Orchestra with the hope of having the violin finished off by Charles’ luthier friend who made his lovely cello. The varnished violin, missing tailpiece, bridge and strings, went to San Francisco.

The maker reshaped the fingerboard, replaced a missing peg and rebushed the other three, made a bridge and recalculated its placement according to the original specs. He put on strings and wrote up the bill for a third what the work was worth.

Yesterday, the luthier returned the Curatoli in working condition, and as fate would have it (I love to say “as fate would have it”) the young violinist happened to be at the house at the time, taking a piano lesson. The luthier handed over the violin. Four of us waited breathlessly to see what the violin would sound like.

First things first: She tuned it, she borrowed a bow, and she tucked it under her chin. Then she played the beginning of a Bach violin concerto. It was beautiful.

=============

Michaele Benedict lives in the “artist community” of Montara. Her latest book is called “Searching for Anna.”

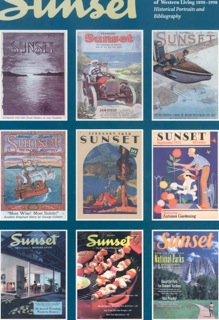

[Image Below: “Sunset Magazine: A Century of Western Living (1898-1998: Historical Portraits and Bibliography. Great book.]

A new-old story by June Morrall

Laurence W. Lane knew why Sunset Magazine was failing. It was a publication about the West–but not for the West. And he was committed to that powerful vision when he arrived in San Francisco in 1928.

Success to the tall 38-year-old advertising director from Des Moines, Iowa, meant putting Sunset Magazine in most West Coast households. Lane was a pioneer in recognizing that the West differed from the rest of the country as he transformed the publication into the “The Magazine of Western Living.”

Sunset was for Western families, explained Laurence Lane’s son, Bill, who was the magazine’s publisher for many years. “Western lifestyle was unique, more adventuresome and daring.”

Sunset Magazine began as a 16-page pamphlet distributed free in the 1890s by its publisher, the Southern Pacific (SP) Railroad. The SP used it as a publicity tool to lure Easterners to the West Coast with colorful stories about California. But by 1914, with its promotional job completed, the SP returned to railroading and the magazine was sold to Woodhead, Field & Co.

Despite the publisher’s attempts to make it “The West’s Great National Magazine,” Sunset was failing when Laurence Lane bought it just months before the “Wall Street Crash”making his challenge to revitalize it even more daunting.

Lane had been the advertising director at Meredith Publishing Co. in Des Moines, publishers of Successful Farming and Better Homes and Gardens. That experience was vital for his task in California.

Lane immediately began reshaping Sunset. He kept the travel department and worked hard on the male readership, said Bill Lane, who has passed away since this interview.Research indicated that unlike their Eastern counterparts, a higher percentage of men in the West shopped for food, cooked, and gardened, areas featured by the reshaped magazine.

With more than 2 million families living in California, Oregon and Washington, Lane reasoned, a quarter of them belonged to a potential market for a regional Better Homes and Gardens type of magazine. The profile of Lane’s typical reader or subscriber was one who owned a home worth $5000 or more, above average at the time, and had an interest in home life, especially outdoor living.

Lane anticipated that he could best reach the homeowner with a Western how-to-do-it slant, a magazine specializing in Western food, gardens, homes, travel and crafts. That editorial formula became Sunset’s signature, and its key to success.

Early on, decisions were made to eliminate bylined articles and editors were encouraged to contribute and develop their ideas, writing the articles themselves. His first issue contained two-thirds more factual how-to-do-it information on Western living than ever before.

The how-to formula was carried over to all sections of the magazine. Even a backpacking trip to Yosemite was described with the same kind of detail found in the directions on a box of cake mix.

Sunset was a hit.

Although the Depression years were rough on Sunset, the magazine survived, and by 1936, Laurence Lane could confirm he was in the black.

Having grown up on a farm in Illinois, Lane loved the outdoors and he purchased a 500-acre horse ranch for $6000 in the Santa Cruz Mountains. Today Quail Hollow is a county park.

Sunset was almost entirely family owned, with Laurence Lane’s sons, Bill and Mel, engrossed in the daily operations. Lane’s wife, Ruth, a home economist, and president of the Palo Alto Garden Club, contributed her talents from the very beginning.

In the early 1950s, Laurence Lane, who had been publishing the magazine in San Francisco, acquired 7 acres of land along San Francisquito Creek in Menlo Park for Sunset’s present-day headquarters.

Renowned landscape architect Thomas Church designed the oak tree-studded gardens surrounding the distinctive ranch house office building, designed by Cliff May, at Middlefield and Willow Roads.

The Lane boys, Bill and Mel, became more involved. Bill was publisher between 1960 and 1985, then was appointed Ambassador-at-Large, first to Japan and later to Australia; he resumed his role as publisher in 1989.

Mel headed up the separate book publishing company, echoing the how-to-do-it theme in the magazine.

Under the Lane family’s management, the magazine pushed forward, focusing on the latest advances in gardening, travel, home building and publishing new food recipes first tested in Sunset’s fully equipped modern kitchens.

Sunset was always in the forefront. It was apparent that people gardened differently in San Diego and Seattle, leading to the introduction of three different editions of the magazine.

“We published articles on “ecotourism” before the word was coined, working with travel agents to seek out-of-the-way places,” said Bill Lane.

And when a proposed freeway running from Menlo Park to the Coastside, threatened Sunset’s Willow Road headquarters, the Lane family searched for a new location, finally settling on 3000 Sand Hill Road.

The freeway did not materialize, but Lane says they were “pioneers on San Hill Road,” which in 1999 housed some of the most expensive office space in the nation.

When Laurence W. Lane died in 1967 at age 76, Sunset Magazine , with four zoned editions, reported a circulation of more than 850,000.

In 1990, Time-Warner acquired Sunset, and the venerable publication celebrated its centennial in 1998.

———

A new-old story by June Morrall

———————————

Story by Peter Adams

Story from John Vonderlin

Story from John Vonderlin