A Little Gossip Beside the RR Tracks

Hello!

Murder in Montara: Babes in the Woods Case, Part VII

In October 1946, several months after Lorraine Newtonâs daughters were brutally slain in a remote Montara canyon, the young 21-year-old mother, herself a victim who survived the attacks, sat in the Redwood City office of Assistant District Attorney Fred Wycoff.

She was ready to talk about the horrific event that had occurred, just days before the murder trial of her husband, Vorhes, was set to begin.

You wouldnât have known Lorraine had been severely injured. Slim and dark-haired, she looked gorgeous after a long hospital stay in Half Moon Bay.

âMy husband, Vorhes,â? she said, âkilled my babies and tried to murder me. He would have buried all three of us in Wagner canyon but he must have been frightened off by my screams.â?

When asked for a motive, Lorraine Newton looked blank. âThere was no reason,â? she said. She noted that the children were his and she didnât have any lovers to make him jealous.

She gave more details about that terrible day recalling that she and her husband headed from Alameda for an appointment with a Doctor Anderson in San Francisco. Apparently the husband made the appointment.

(While there may have been an authentic “Dr. Anderson” in San Francisco, there was a Mrs. Alta Anderson, who, along with her daughter, Mae Rodley, operated an “abortioon mill” in San Mateo County. Is it possible that this is the “Dr. Anderson” both Newtons, or the wife or the husband, had made an appointment with?)

âHe said he wanted to take a ride first,â? Lorraine said. She seated Barbara, the older daughter in the front seat between the couple, and Carolyn, was put in a baby seat in the back.

Vorhes may have wanted to take a âride firstâ?, as Lorraine claimed, but she said they did go to San Francisco. When they got there Vorhes said that the doctor was not in San Francisco but at Rockaway Beach in Pacifica.

With the car pointed in a new direction, they drove into the mountains and stopped. âI couldnât understand what a doctor would be doing in the wilds,â? she said.

âI got out of the car and Vorhes struck me. He hit me with his fist. He knocked me out. When I came to one baby lay head beside me. The other baby was half buried. I never saw her.â?

Lorraine Newton said she was going to testify against her husband. âI will answer questions,â? she said. âIâm only interested in seeing that justice takes its course.â? One would think her tone would be angrier, uglier, but she only added that, âFor myself, I want to forget everything. I have no plans, not even to divorce my husband. I suppose Iâll ask for my freedom later.â?

The Newtons met while they were students at Polytechnic High School in San Francisco. Vorhes had joined the Coast Guard when the couple married in Reno in 1942.

â¦.To be Continued

Owen Bryant: Our “Beetle Man” in Montara, Part II

At the California Academy of Sciences, amateur entomologist Owen Bryant met Dr. Blaisdell, a Stanford doctor and insect expert who named some of Bryantâs beetles. Owen also befriended Hugh B. Leech, the Associate Curator of Entomology, and the man who would write Bryantâs obituary in 1958.

These were the experts who attracted the beetleman Owen Bryant and the reason he moved into the old Montara schoolhouseâso he could live close to the Academy located in Golden Gate Park.

When Owen and Lucy Bryant moved to Montara, lthey also purchased two building lots in the El Granada Highlands. Owen believed they might have oil beneath them as he had seen oil operations nearby. At any rate he had a special understanding of the petroleum business.

Dr. Ross suggested that oil was the source of Owenâs income. He was the president of the Calgary, Alberta-based Bryant Oil Company, and, while not rich, income from the venture sustained his lifestyle, enabling him to pursue his bug interests.

âHe had a dictatorial father,â? Ross told me four years ago. âI believe his father wanted to send poor Owenâwho was basically a bug collectorâto school to become a doctor.â?

Owen Bryant, who was born in Brookline, Mass. In 1882, attended Harvard, but according to his correspondence stored at the Academy, he did poorly in English courses, failing four times. He repeated the class until the sympathetic instructor passed him so that he could enter medical school as his father wished. He graduated from Harved in 1904 and spent three unhappy years attending medical school.

As soon as summer break came, the naturalist in Owen prevailed, and he was off to the Bahamas, Newfoundland, Labrador and Java collecting birds, mammals, reptiles, seashellsâand his beloved insects.

Then, in 1908, Owenâs father died and he was free, and that meant the end of his medical career.

Clearly Owen had enough income to become a gentleman collector. But he was scarred by the frustration of being forced into the medical education he did not want and the trauma of the failed English classes.

In 1939, in response to an âanniversary surveyâ? from Harvard College, an angry Owen responded:

âI have made it my business to avoid business and professional relations of each and every sort,â? he wrote, âbut have had the misfortune to be n ot quite able to keep out of the clutches of the legal and medical professions.â?

In discussing his lifelong commitment to observing insects, he sarcastically wrote: âMy hobby is the same one I have been engaged in most of my time for the last sixteen years, the puerile one of catching bugs, presumably begun then because I entered my âsecond childhoodâ at that time.â?

When reporting public service activities, Owen ridiculed the question by snipping that he had âtrapped one pack rat and four mice.â?

These were the words of an embittered man.

But the years smoothed Owenâs rough edges. In 1954, now living in Montara, he was again asked to respond to another Harvard College survey. This time Owenâs anger was gone. He matter-of-factly cataloged his affiliations and accomplishments, dryly observing that he was âstill at itâ?, that is collecting his insects.

The passage of time and Owenâs pleasant relationship with the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco were surely responsible for his mellowingâbut he never recovered from the trauma of flunking English classes at Harvard. That horrid experience blocked Owen from ever becoming a bona fide scientist. He believed he could not write well enough to author the all-important papers that were required.

For his entire life as a collector, he never could do the writing himself. It was always up to others. Someone had to correct his grammar and someone had to do the typing and someone had to address the letters to the appropriate person. The problem was solved when he married Lucy McBride in 1932. She was a competent secretary who helped her husband deal with all of his deficiencies.

Owen and Lucy were a good match.

Photo:  Lucy McBride Bryant, Special Collections/California Academy of Sciences

Lucy McBride Bryant, Special Collections/California Academy of Sciences

In his correspondence, Owen recounted that wife Lucy was a scrapper. He told of one incident when she faced up to water officials in Montara, claiming that the Bryants were not getting their proper amount of water. In spite of the bureaucracy, she prevailed.

In 1957, Lucy McBride died. Her death hit Owen very hard and he became morose. He gave a treasured insect storage case to Paul Arnaud, an acquaintance from Redwood City. The old Owen would never have parted with his equipment but it was clear that even his precious bugs could no longer hold his interest.

On October 26, 1958, the 76-year-old amateur entomologist Owen Bryant passed on. He left his entire estate to the California Academy of Sciences in Golden Gate Park. The estate included the Montara Grammar School, the El Granada Highlands building lots, boxes of correspondence, photosâand, of course, his beloved insect collection.

(The property was sold but the correspondence, photos and insects remain as part of the California Academy of Scienceâs collection).

Dr. Ross recalls revisiting the Montara schoolhouse shortly after Owen Bryantâs death. He was very moved when he saw Owenâs family photographs strewn across the cover of the king-size bed in the bedroom/classroom.

Perhaps Owen Bryant had been studying those photos, reviewing his own life.

âThe Bryants were gypsies of a sort,â? Dr. Ross reflected. âBoth liked that life and they would not have lived long in that schoolhouse. One day they would have gotten itchy feet, and said, âLetâs go to Costa Rica. The insects are good down there.â?

Second Thoughts: Richard Schellen

Come to think of it, Richard Schellen was a like a “human database”, databasing before computers were doing it for us. Just think what Schellen could have done with a computer.

I don’t know for certain if the Richard Schellen Collection is accessible online, but wouldn’t it be nice if it were? What a terrific project for someone to underwrite–and make available to anyone through the library or the county history museum. That would be the greatest tribute to Mr. Schellen.

Owen Bryant: Our “Beetle Man” in Montara, Part I

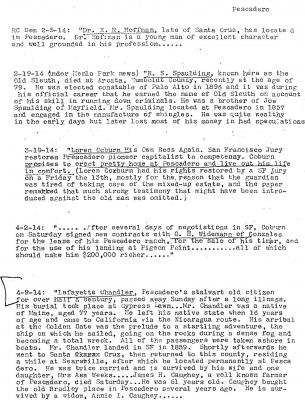

At left: Owen Bryant (Special Collections/California Academy of Sciences)

At left: Owen Bryant (Special Collections/California Academy of Sciences)

In an earlier post I wrote a tribute to Richard Schellen, the wonderful Redwood City librarian, now gone, not only makes researching Coastside history fun â- sometimes he turns it into one of those special âEureka!â? moments.

A while back, I had one of those lucky experiences.

While flipping through the Schellen Collection, I was zeroing in on Montara, when I became fascinated with a 1958 obituary. The subject was Owen Bryant, an amateur entomologist, who resided with wife, Lucy, and their collection of 200,000 mounted insects in Montaraâs historic two-story schoolhouse.

Wow! A bug collector in the old grammar school? I had to know more.

This is how it worked: The Schellen Collection steered me to the original newspaper article with the complete obit– and the Eureka! I needed to further my research: Owen Bryant had nurtured a close relationship with the California Academy of Sciences in San Franciscoâs Golden Gate Park.

A phone call later, I learned that the Academy of Sciences had it all.

Four years ago, on a rainy winter afternoon, I sat in the curatorâs offices, looking through several boxes of Owen Bryant biographical info. I also met Dr. Edward S. Ross, then the 86-year-old curator-emeritus of entomology. He had been with the Academy since 1939, an expert in 300,000 species of insects, but he was even more famous as a âclose-upâ? photographer. The walls of his office were covered with the extraordinary pictures of people, places and wildlife that had been published in college textbooks and National Geographic.

In the early 1950s, Dr. Ross visited the Bryants at Montara, followed by dinner âat the restaurant (Frankâs) on the nearby beachâ?. Ross clearly remembered seeing the bell towers of the two-story Montara Grammar School from Highway 1.

Ross remarked that the 60-x90-foot former schoolhouse had been converted into an unusual residence. On the first floor Owen and Lucy used a classroom as a bedroomâpushing their king-size bed up against the blackboard. One of the few things that brightened the surroundings was a museum quality of Mt. Resplendent in the Canadian Rockies. There were many boxes yet to be unpacked, including some containing Lucyâs inherited silver.

None of Owenâs prized insects could be seen on the first floorâalthough upstairs there was a âbug roomâ?, office and library shelves overflowing with naturalistâs books bounds in fine Moroccan leather and gold tooling.

Photo at left: During the 1950s Montara Schoolhouse was home to the Bryants.

Photo at left: During the 1950s Montara Schoolhouse was home to the Bryants.

Did the reclusive Owen and his vivacious wife, Lucy, find Montara dullâinsect-wise? They had just come from a favorite bug-hunting area on the outskirts of Tucson, Arizona. Insect collecting was outstanding there at the base of the Santa Catalina Mountainsâespecially during Arizonaâs rainy âmonsoonâ? season when there was a great burst of life in the desert at night. The wind was soft, the flowers were fragrant and it was âgangbustersâ? for beetle hunters. Owen, wearing bug-collecting gear, and armed with a stick, beat the bushes, overturning stones to unearth his prized insects.

âOwen had a great time in Arizona,â? Dr. Ross told me. âFrom moment to moment he didnât know what kind of beetle was going to bounce in. It was like manna from heaven. Most people would say, âUgh!â Owen Bryant said, âAhh!â?

Before settling down in Montara, Owen hadnât stayed put for very long. He and Lucy were rootless, always moving from one place to the next: Alaska, Banff, Canada, Steamboat Springs, If anyone wanted to locate the Bryants, all they had to do was find out where the beetles were flourishing and Owen and Lucy would be there.

Dr. Ross said that Owen Bryant had moved to Montara âto be near the Academy. He came up here once a week with boxes of things.â?

Owen needed the experts at the Academy of Sciences to identify his insect specimens. Sometimes he brought in a beetle that had never been seen before and the scientists named it.

Beetles were Owenâs greatest interest and by 1950 he had donated 38, 530 specimens. Ross pointed out that many accomplished people were amateur collectors of insects. Charles Darwin, for example, was fascinated with beetles because of their tremendous diversity.

At the Academy Owen Bryant found more than expert entomologists; he forged enduring relationships with the scientists and the institution.

Dr. Edward Van Dyke, who had been there since the early 1900s âwas a famous beetle person,â? Ross said, âan M.D. who practiced medicine but his real passion was the bug collection he kept in the back office. Whenever the patients werenât around, Van Dyke was in the back room.â?

â¦To Be Continued

Mechanically Speaking

Thank you, Richard Schellen

Years ago, when I first started searching through old newspapers for stories on the Coastside, a helpful librarian steered me to the “amazing” Richard Schellen Collection.

I cannot praise Richard Schellen enough for the work that he left anyone interested in local history, or a specific event, such as when a building was built or burned.

Mr. Richard Schellen was once Redwood City’s head librarian, but I think of him as a librarian’s librarian.

This wonderful man organized and typed up thousands of stories– either in their entirety or the first few sentences, (you could always find the longer original) –and he organized these stories by date and town, in some cases going back to the mid-19th century and earlier.

In the Schellen Collection you can find political stories, business stories—murder stories….Perfectly organized by town and date. It’s a great resource.

I wish I could have met Richard Schellen to thank him personally. He gave us writers and historians and the folks of San Mateo County so much.

The Schellen Collection can be viewed at the main Redwood City library as well as the San Mateo County History Museum, located in Redwood City’s old courthouse.

Here’s hoping you enjoy the collection as much as I did.

A sample page from the Richard Schellen Collection–this sheet lists a few stories about Pescadero. Click to enlarge.

A sample page from the Richard Schellen Collection–this sheet lists a few stories about Pescadero. Click to enlarge.