Exotic Poppies: All Done

Summer Reading: The Story of Jane Lathrop Stanford (4)

This is the story of Jane Lathrop Stanford and the mysterious circumstances surrounding her death in the early 1900s.

Part 4

The servant staff resented secretary Bertha Berner’s influence over Mrs. Stanford, and worse, when ordered to obey Bertha, the “people below the stairs” became intensely jealous.

The servants often gossiped about Mrs. Stanford’s last will. They were certain Bertha Berner was in it and the private secretary was certain they were right.

Instances of petty jealousy pervaded the household. Wong Wing, the Chinese housekeeper, the senior member of the servant staff, who had worked for Jane Stanford the longest, abhorred taking orders from Bertha Berner.

Now wonder Wong Wing became agitated when Bertha ordered him to make her a cup of coffee every afternoon. Finally he became angry about the extra “duty” and complained to Mrs. Stanford who commiserated with him.

Learning of the conversation, an annoyed Bertha Berner burst into the kitchen, reportdly confronting Wong Wing: “You made trouble for me with Mrs. Stanford,” she charged. “I will make a lot of trouble for you and everybody else.”

Despite his seniority, and Mrs. Stanford’s sympathy, Wong Wing was also a victim of household rumors. It was said that when Mrs. Stanford’s brother, Harry, died, the Chinese housekeeper told her that Harry promised him $1,000. Without asking questions, Mrs. Stanford gave him the cash, while the servants downstairs whispered to each other that Wong Wing’s story was a lie.

And what was the true nature of the relationship between Bertha Berner and the “shrewd” butler, Albert Beverly?

(Part 5 coming)

Summer Reading: The Story of Jane Lathrop Stanford (3)

This is the story of Jane Lathrop Stanford and the mysterious circumstances surrounding her death in the early 1900s.

Part 3

By June Morrall

When Leland Jr. sailed to Europe in 1884, it would be their last time together. The teenager collected his souvenirs, but while visiting Florence in Italy, he fell seriously ill with typhoid fever. Jane and Leland Stanford’s only child failed to rally, and Leland Jr. died at age 16.

Their son’s tragic death devastated the Stanfords. Jane’s migraine headaches intensified, and she felt a crushing sadness, lessened only by occasional visits to spiritualists. Constant travel also became a palliative to dull her pain.

One account releates that while Leland Stanford sat at his feverish son’s beside he fell asleep and dreamed his son said: Father, don’t say you have nothing to live for, you have a great deal to live for, live for humanity, father.

Perhaps the dream led Jane and Leland Stanford to co-found Leland Stanford Jr. University on the site of their Palo Alto Farm soon after their son’s death. About the same time Leland Stanford was elected US Senator by the California State Legislature.

The cornerstone of Stanford was laid in March 1887. Four years later, the first class of 559 students was enrolled, with David Starr Jordan, a doctor of medicine, named president of the new institution.

Deep sorrow struck Jane Stanford again when husband Leland passed away at age 69 in 1893. To blunt this second sorrow, the widow became absorbed in the work of the university. When visiting the college she stayed at her home located near the campus.

The major portion of the university’s endowment came after her husband’s death. In 1897, while reserving life tenancy for herself, Jane gave the university trustees a deed to her Nob Hill mansion for the establishment of departments of economics, history and the social sciences.

Seven years later, the melancholy Mrs. Stanford had long slipped into a routine of traveling extensively, with her longtime private secretary and a butler in tow. While away from San Francisco, she maintained a servant staff at the Nob Hill mansion, including a maid, Chinese housekeeper, houseboy and two cooks.

When at home, she waas kind but distant to the servants, allowing little familiarity on their part.

This rule did not extend to Bertha Berner, Mrs. Stanford’s well-groomed, private secretary–a spinster earning a $200 monthly salary who traveled the world with her employer in utmost comfort.

Wearing her gray hair in a becoming pompadour, Bertha Berner was treated as a companion or guest. Strong and assertive, Bertha, more than anyone else, understood Mrs. Stanford’s whims and eccentricities. Her bedroom at the Nob Hill mansion was located up the grand staircase on the second floor next door to Jane’s bedroom. Bertha’s room served both as her office and as a quiet place where she passed most of her personal time.

By 1904 Jane Stanford dwelled unnaturally on the sad events in her life, demanding more attention from those around her. There were rumors Bertha threatened to quit more than once and that Mrs. Stanford’s brother, Charles Lathrop, paid Bertha an additional salary to stay on–all negotiated without his sister’s knowledge.

(Part 4 coming)

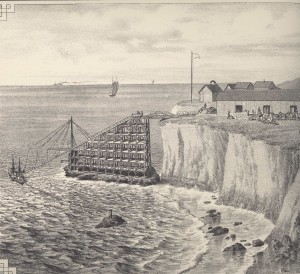

1870s: Alexander Gordon’s Incredible Chute at Tunitas

Summer Reading: The Story of Jane Lathrop Stanford (2)

This is the story of Jane Lathrop Stanford and the mysterious circumstances surrounding her death in the early 1900s.

By June Morrall

One year befoe Leland Stanford drove home the golden spike, wife Jane gave birth to Leland, Jr. in the richly furnished surroundings of her Sacramento mansion. The Stanfords had had a long childless marriage, now the couple rejoiced, and the baby boy became the center of their lives.

At an exclusive dinner party, the infant was passed around on a silver platter for guests to admire.

With their great wealth, the Stanfords built a stately residence high atop San Francisco’s Nob Hill, with sweeping views of the bay as well as the Central Pacific Railroad depot. Within the walls of what was described as the largest private residence in California, Jane Stanford entertained leaders from all over the world.

An eclectic decor accentuated the interior of the Nob Hill mansion. Soon after being greeted at the front door by a maid or butler, distinguished guests walked across a marble floor inlaid with a zodiac, while 70-feet above their heads sunlight filtered through an amber glass skylight.

Music of the era flowed through the mansion; its source a huge “music box.” In the East India room visitors studied Gov. Stanford’s mementos; they admired the furnishings in the Chinese room, reportedly provided by the Chinese government and lingered in the mosaic-decorated Pompeian room. Guests experienced a mild shock upon discovering an artificial jungle with mechanically chirping birds in the art gallery.

Leland’s business interests and Jane’s love of travel abroad often separated the pair, but when the couple was together, Leland revealed a romantic side.

On one occasion, he chose Italy’s stunning Lake Como as a backdrop for a surprise birthday party for Jane.

In the morning, Leland presented his wife with an enameled box of jewels; at sunset he arranged for her to be serenaded by musicians aboard a barge draped with hundreds of fresh flowers.

All that was missing in their lives was a country home on the Peninsula.

In 1876, the Stanfords purchased “Mayfield Grange” from Mrs. George Gordon, on eof the notorious characters in local novelist Gertrude Atheron’s scandalous 1899 book A Daughter of the Vine. The Stanfords renamed the acres of vineyards, orchards, stock farm and race track the Palo Alto Farm.

Young Leland Jr. frolicked in the stables and rode his father’s sleek, fast horses across the fields and over the hills. He displayed a talent for languages and a curiosity for archaeology, filling his doting parents with immense pride.

But when Leland Jr. sailed for Europe with his mother in 1884, it would be their last time together.

(next Part 3)

1912: Road Rage over the hill in San Mateo (4)

I wrote this in 2001.

Prominent oil executive’s son collides with irate chauffeur

Captain Barneson was also known for his stores of another kind of lubricant.

Captain Barneson was also known for his stores of another kind of lubricant.

During Prohibition it was common knowledge that the Peninsula’s wealtheir residents kept vst stocks of fine wines and imported whiskies in secure vaults, and it was no secret that Capt. Barneson’s inventory was among the best.

When rumors spread that an afternoon blaze was about to “lick up” Barneson’s illicit treasure at his beautiful San Mateo County home, volunteer fire fighters piled into automobiles, hopped onto motorcycles and rushed to the scene.

The fire fighters broke all previous records in the dash from San Mateo to the Barneson home. It was clear they were motivated by their civic duty to protect life and property.

“It was not every day that the populace of San Mateo was given an opportunity to aid in the saving of a vast store of liquor such as was reported to be housed at the Barneson county residence,” said one newspaper.

When the firefighters got there, they found nothing ablaze. The alarm was due to a defective flue on the upper floor of the Barneson home. How disappointed they were to discover that Captain Barneson’s liquor stock, valued at $50,000, remained safe in the fire-and-burglar-proof vaults in a sub-basement.

They went home sober and sad.

When Captain John Barneson passed away in Hillsborough in 1941, this son of a Scottish ship owner was heralded as one of the pioneers in the development of California’s petroleum industry. But on that Sunday in 1912, when frightened by his son’s automobile accident in San Mateo, he reacted like any other father.

1912: Road Rage over the hill in San Mateo (2)

I wrote this in 2001.

Prominent oil executive’s son collides with irate chauffeur

After hearing testimony fro Captain Barneson, his son, Harold, and Gallois, chauffeur James Irving pled guilty to speeding within the city limits and was fined $15 by San Mateo’s City Recorder.

But James Irving had countercharged Harold Barneson with breaking the county’s speed laws, and this case was tried before a jury in Justice of the Peace H.W. Lampkin’s Redwood City courtroom.

The socially prominent Barneson and Gallois families attracted many local spectators to the legal proceeding. There was no shortage of stylish young ladies in the audience whose loyalties to Harold were evident.

Enlivening the proceedings was the testimony of Captain Barneson, who described the chauffeur as a “pinhead,” but was quickly admonished by Justice Lampkin, who advised the witness to hold his opinions and simply answer the questions.

The packed courtroom buzzed with excitement, then fell silent as the jury’s verdict was read. Harol Barneson was acquitted and the courtroom exploded with applause.

But the case was not over for the chauffeur. He pled guilty to going around corners without regard to the rules of the road. Justice Lampkin, displaying remarkable judicial restraint, suspended the additional fine, remarking that many had been guilty of similar offenses.

The final accounting showed that Captain Barneson, besides landing the big upper cut, was instrumental in having Irving fined $15 for speeding and $5 for not following the rules of the road in going around a corner. Captain Barneson also scored a technical victory in the acquittal of his son on the speeding charge.

1912 was a very good year for Captain Barneson. By then, he had earned the reputation as one of the largest–if not the largest–individual owners of oil properties in California.

Although his varied business interests were rooted on dry land, Captain Barneson would much sooner have been at sea. He was established as one of the country’s leading yachtsmen. While in New York he purchased the handsome 85-foot schooner, Edris, outfitted with a Craig engine that enabled the vessel to move at about eight knots.

Bringing the Edris to her home berth in San Francisco required sailing around the Horn–a dangerous and challenging voyage.

Arriving in San Francisco safe and sound, Captain Barneson made a wager with a man named Commodore Mitchell that he could beat the commodore’s Yankee Girl in a race from Long Beach to Coronado Beach, with the loser paying for a $1000 dinner at the Hotel Del Coronado.

On the day of the yacht race, a 20 -mph breeze churned the sea. Following the yachts along the seashore were several automobiles filled with the socially prominent from the Peninsula and Los Angeles. One of the automobiles was equipped with a wireless apparatus enabling the occupants to communicate with the yachts throughout the race.

While Commodore Mitchell chose to stick close to the shore, seaman’s luck was with Captain Barneson, who took an outside course and won the race by half-an-hour.

A year later, now commodore of the old San Francisco Yacht Club, Barneson took over responsibility for major yacht races, including the Presidential Cup featured at the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco.

(Part 3 coming)

Honorary Chairs at the Ocean View Lodge, IOOF Bldg on Main Street

The Ocean View Lodge is located on the top floor of the IOOF (International Organization of Oddfellows) building on Main Street in town. Above M. Coffee and Tokenz.

Members of the lodge, led by Tony Pera, have turned the upstairs rooms into their original splendor–the way it was in the 1870s when this was the most important organization in Half Moon Bay.

When I use the word, “splendor,” I don’t mean “fancy” or “luxurious.” The main room is of simple design with well made furniture reflecting the solid nature of the town’s citizens.

The three chairs were reserved for the officers of the lodge.

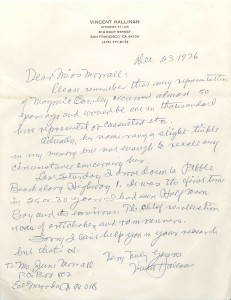

1976: Letter from Vincent Hallinan

When I was doing research on Maymie Cowley, the madam at the Miramar Beach Inn, a friend suggested that I write San Francisco columnist Herb Caen. “He knows everybody,” the friend reminded me. I did write Caen, asking about Maymie, and Caen’s assistant looked into the files and came up with a story linking famous attorney Vincent Hallinan with Maymie Cowley. The story, a small clip, reported a government raid on Maymie’s roadhouse during Prohibition–and that Vincent Hallinan was representing her.

But when I wrote Vincent Hallinan in 1976, hoping he would hand me a big story, it was many, many legal cases after his brief connection with Half Moon Bay’s madam.

Dec 23, 1976

Dear Miss Morrall,

Please remember that my representation of Maymie Cowley occurred almost 50 years ao and would be one in thousands I have represented or consulted, etc.

Actually, her name rang a slight tinkle in my memory but not enough to recall any circumstance concerning her.

Last Saturday I drove down to Pebble Beach along Highway 1. It was the first time in 25 or 30 years I had seen Half Moon Bay and its environs. The chief recollection was of artichokes and rumrunners.

Sorry, I can’t help you in your research but that’s it.

Very truly yours,

Vincent Hallinan