(Note: The true story of âKid Zugâ? was stitched together, using old newspapers to pick out a description here, another thereâuntil I gathered enough pieces for a word picture).

âKid Zugâ?: Part I

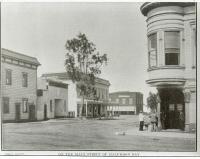

In 1918 workmen hurriedly erected an outdoor prize fight ring on the saloon-fronted San Gregorio Street in Pescaderoâand everybody buzzed about the upcoming boxing match between the newly arrived âKid Zugâ? and his local opponent, âHappyâ? Frey.

In California boxing was illegalâso was gamblingâand had it been any place other than Pescadero, the authorities would have clamped down. But this was Pescaderoâwest of the magnificent redwood forest on San Mateo Countyâs remote South Coastâand outsiders didnât care (or know) what was going on there.

The village of Pescadero was about 70 years old in 1918âbut it was local lore that you could tell what was fashionable by the contents of the cargo salvaged from the last shipwreck.

In the 1890s, for example, horse-and-buggy tourists were surprised to see every single house in town with a fresh coat of white paint. They learned that the Pescaderans had been the beneficiaries of a bonanza in the form of tons of paint salvaged from the shipwrecked vessel Colombia.

A quarter century later it was more likely that the villagers would be salvaging cases of illegal liquor from the unlucky bootlegging fishing trawlers that had crashed into the dark rocky reefs on moonless nights.

Newcomers to the Coastside village, particularly those with the ârightâ? connections, quickly discovered that slot machines and card games were found in a two=story house at a curve on the lonely road leading east into the redwoods.

Even more fascinating were the rumors that certain county officials were regularly in attendance, playing the one-armed bandits.

Among the intriguing newcomers was a ruddy, scar-faced ex=pugilist who called himself âKid Zugâ?.

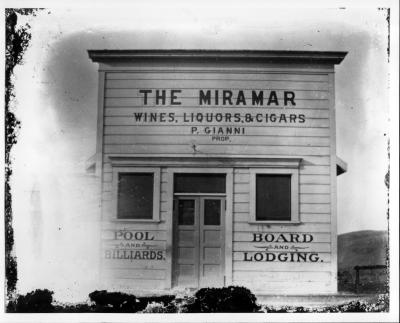

He was seen paling around with the owner of the gambling joint. Although âthe Kidâ? explained his presence in town by saying he was a house painter, he was never seen holding a paintbrush. He was much more often seen tipping back a glass of beer at one of the four saloonsâand he never ceased menacing those around them.

It didnât take long for the locals to learn the truth: Kid Zug was really in town to act as a strong-arm enforcer.

To be continuedâ¦.