“Down the Ocean Shore”, an a tour by automobile from the pamphlet, “The Chapter in Your Life Entitled San Francisco”, published in 1946 after WWIIHalfby Californians, Inc. The trip began near Pacifica, and the mileage figures begin there; see Part I back a few posts.

Half Moon Bay, 20.6 m is farm village at northern end of the blue bay bordered by a long white beach. Back from bay are small farms with whitewashed barns, weather-beaten farmhouses, sheltered from wind by lines of dark cypress trees. The Portola expedition pitched camp near mouth of Pilarcitos Creek, northern edge of town, on rainy night Oct. 28, spent wet, miserable weekend.

Purisima, 24. 8 m., once lively town on Rancho Canada de Verde y Arroyo de la Purisima, is deserted and ghostly now. From Viewpoint, 28.9m, tawny bluffs bordeered by surf stretch S.

Next comes San Gregorio Valley, 32.4m, with hidden farm hamlet reminiscent of early Spanish rancho days, where suave hills sweep up to Sierra Morena crest.

Pescadero (fishing place), 39.8m, small settlement, its prim white buildings having look of New England village, got its name from Pescadero Creek. This trout stream and its lagoon are still good fishing places.

At 40.8m is junction with dirt road; R. here 2m to Pebble Beach, famous for polished stones–small agates, jaspers, opals, moonstones, waterdrops (pebbles with drops of water in their centers).

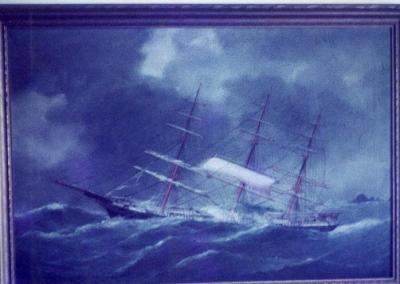

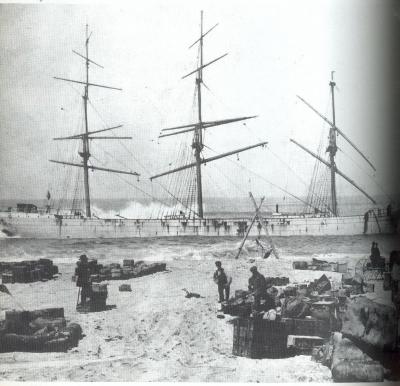

Next comes Pigeon Point Lighthouse, 46.1m, overlooking rocky coast on which Boston clipper “Carrier Pigeon” was wrecked in 1853.

Punta del Ano Nuevo (New Year’s Point), 53.8m, forms southwestern tip of Peninsula. Was first important headland sighted Jan. 3, 1602 by Sebastian Vizcaino’s crew when they sailed up coast from Monterey. Here pine-forested mountainsides slop steeply to the sea, crowding highway to edge of narrow beach. (Note: experienced Peninsula travelers say that views are even more spectacular if the route is taken driving N. from Punta del Ano Nuevo toward San Francisco).

Dining & Dancing

Princeton-by-the-Sea

Nerli’s Place

Half Moon Bay

Dominic’s Place

Red’s Place

Pescadero

Duartes, San Gregorio St.

Photos: Beginning at top: Main Street, HMB, at left, location of Dominics; Peterson & Alsford Store, San Gregorio; Pebble Beach w/hotel on bluffs, south of Pescadero; Pigeon Point lighthouse; Frank’s, Moss Beach; Bar inside Duartes, Pescadero.

credits: San Mateo County History Museum, R.I. Guy Smith

Note: The photos didn’t appear in the original pamphlet.