At the foot of Montara Mountain, an artistâs colony, the dream of San Francisco publisher Harr Wagner and his poet wife Madge Morris, seemed to be unfolding in the most beautiful way.

At the foot of Montara Mountain, an artistâs colony, the dream of San Francisco publisher Harr Wagner and his poet wife Madge Morris, seemed to be unfolding in the most beautiful way.

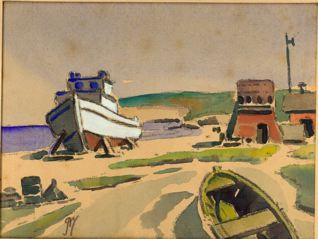

A few quaint cottages were built and artists moved in with their musical instruments, pens and watercolors. The nearby streets were named in honor of authors Bret Harte, Elbert Hubbard and Rudyard Kipling. A bakery opened its doors and many in Montara viewed the new community as economically self-sustaining.

Harr constructed a family residence featuring stone pillars and a circular driveway. To establish a sense of tradition at Montara-by-the-Sea, he organized annual barbecues, attended by his artist friends.

Mussels were harvested from the nearby beaches and placed in steaming kettles while steaks sizzled on the open grills. Harr presided over the festivities, always the jovial host attired in chefâs hat and white apron.

Perhaps in anticipation of the flood of tourists attracted to the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, Harr helped construct a lovely resort hotel framed by the warmth of Montara Mountain.

But Harrâs reputation for taking risks that generally failed was not about to change. The artist community at Montara was no exception.

The Ocean Shore Railroadâthe artery that carried life to Montara and other Coastside beach townsâfiled for bankruptcy and pulled up its rails. A fire swept away the resort hotel and a future conflagration would take the Wagnerâs family residence, leaving only the stone pillars.

The Wagner family, which included daughter Morris, weathered the latest financial setback in typical fashion. Harr shrugged his shoulders and humorously labeled himself a âsuccessful failureâ?.

But despite Montaraâs economic reverses, the tiny beach town still retained its identity and lure for artists. Real estate sales may have tumbled but the âVon Suppe Poet and Peasant Cottageâ?, honoring a 19th century European composer, was still in demand at a rental fee of $85.00 weekly.

Meanwhile, daughter Morris was thriving. She had been named the postmistress of Montara, and with an initial investment of $350.00 , began raising those milk goats with good friend Irmagarde Richards.

Within a few years, Morris and Irmagardeâs work won acclaim as observers praised them for âcontrolling the goat industry in this part of the worldâ?.

Their goats were not what Irmagarde labeled the âback alleyâ? sort. She and Morris aimed much higher, raising gold medal winning, blue-blooded Toggenberg goats, the breed that were used in experimental gland transplantation in the elderly.

According to Irmagarde, their goats were attractive and highly efficient milk producers. A steady stream of physicians had made the trek to Montara for goat glands but the women were not interested in that phase of the business.

Their goats provided sweet milk onlyâno parts.

In 1922 goat milk was a valuable commodity because it wasnât produced in large quantities by commercial dairies. This situation enabled Morris and Irmagarde to sign a contract with a tuberculosis hospital in San Mateo to provide 60 quarts of goatâs milk per day. The milk from their herd of 200 goats was earmarked for children with TB who were unable to digest other foods.

Tuberculosis, which most commonly affects the respiratory system, is usually acquired from contact with an infected person, an infected cow, or through drinking contaminated milk.

âToday, after nine years of hard work and fun,â? Irmagarde Ricahrds said in 1922, âwe have one of the best-equipped milk goat establishments in the world.â?

But there years later, in 1925, the world of âthe goat girlsâ? was turned upside down. After a long illness, Morrisâs mother died at Montaraâand technology introduced new baby food formulas into the marketplace.

The demand for goatâs milk dwindled and the Las Cabritas (Little Goats) Farm at Montara quietly ceased production and closed its doors.

Note: I actually met Morris Wagner. She was elderly and lived in a very nice senior home in Los Gatos but what impressed me most was her face, filled with light and warmth and great love, her fatherâs daughter, I felt certain.

Photos: Quaint house in Montara & Montara landscape with Montara Inn perched on the hillside.

Sybil Easterday’s rooster should have awakened her from her deep sleep on the morning of April 18, 1906. Instead the well known eccentric sculptress, who lived with her mother, Flora, in an artistic home at Tunitas Creek, south of Half Moon Bay, found herself captive to the sudden shaking and moving of the earth.

Sybil Easterday’s rooster should have awakened her from her deep sleep on the morning of April 18, 1906. Instead the well known eccentric sculptress, who lived with her mother, Flora, in an artistic home at Tunitas Creek, south of Half Moon Bay, found herself captive to the sudden shaking and moving of the earth.