There was a time when you’d mosey on over to the foggy Coastside and head north to Moss Beach and walk around the tidepools of the Fitzgerald Marine Reserve–and if you were the curious type you’d find a very unusual house at Nevada and Beach Streets– decorated with abalone seashells on the exterior that spelled out “Nye’s Reef’s II”.

This place with the abalone shells was an instant draw.

Knock on the door and you’d discover this is where Charlie Nye lived, an eccentric, loveable guy who opened up his home to visitors whenever he felt like it.

His father, also called Charlie Nye, had been the famous owner of a popular restaurant, featuring his special clam chowder recipe–but his son didn’t follow in his father’s footsteps. Usually wearing a black turtleneck, Charlie Nye, Jr. had one of those small refrigerators, a couple of feet tall, and if you were thirsty he’d offer you a soft drink. That’s as close as he got to the restaurant business.

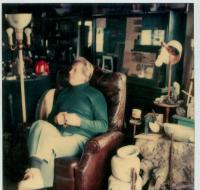

Charlie Nye, Jr. inside “The Reefs II” in 1980 photo by June

photo by June

Charlie’s house was a charming one-of-a-kind– jam-packed with all kinds of old stuff including an antique piano which he played and overstuffed furniture and beach memorabilia and lots of dust .

It was a treat to spend an hour with Charlie.

He loved to chat and talk about his father who came to the Coastside after the Spanish-American War in 1898. “It was the one place he found where he didn’t suffer from remittent malaria,” Charlie told me.

His father settled in at Moss Beach and was introduced to the ambitious Harr Wagner, a San Francisco publisher and land developer who was trying to establish an artist’s colony in Montara. Wagner’s wife was Madge Morris, a published poet–and for the artist’s colony to succeed it was critical that the Ocean Shore Railroad do so, too.

But the timing of the building of the railroad was way off-track–the Ocean Shore Company couldn’t have had worse luck as the earth- shaking tremors of the catastrophic 1906 earthquake ripped up the work that had been done on Devil’s Slide and tossed expensive equipment and rails into the Pacific Ocean.

Not only were they way behind schedule, this was a financial disaster for the railroad, one that the Ocean Shore never recovered from. The railroad’s failure also threatened the success of a famous Moss Beach resort owned by Jurgen Wienke, also known as “the Mayor of Moss Beach”. (There is a street leading to the ocean named after him).

Guests arrived by horse and carriage at Wienke’s Hotel which was his sprawling home and gardens. His wife and daughter acted as hostesses to a bevy of famous guests including Stanford’s president. On the sandy beach below Wienke’s hotel, he constructed a small building with a deck–a seafood restaurant, a place where boats could be rented.

But once the locals surveyed the damage to the railroad at Devil’s Slide, the sound of misfortune filled the air.

Charlie Nye, Jr. told me, unlike the others, his father saw good luck in disguise.

Galen Wolf, Coastside artist.

Galen Wolf, Coastside artist.