To read Dave Holleman‘s memoir on fascinating Tunitas Creek painter Sheri Martinelli, please click here

John Vonderlin: 1894–Fire!!! At the HMB Occidental Hotel!

Story from John Vonderlin

Email John ([email protected])

Hi June,

It took a disaster, but Spanishtown made it into the Record-Union, Sacramento’s newspaper. This story was from the April 13th, 1894 issue. Enjoy. John

FIRE AT SPANISHTOWN.

A Block in the Center of the Place

Destroyed.

Halfmoon Bay, April 12. —Fire broke

out yesterday afternoon in the Occidental

Hotel, destroyed that building, spread to

adjoining houses and consumed almost

the entire block in which the hotel was

located. The only buildings left standing

are the feed mill and two dwellings be-

longing to the J. B. Dollof’s estate and

Charles Bowman’s small saloon building.

The burned block is right in the center

of Spanishtown and included a large por-

tion of the business part of town. The

loss is between $10,000 and $17,000. Had

the flames gained headway on the other

side of Main street 90 per cent of the town

would now be in ashes.

Just In from Oregon: Charlie M. Shears Katie’s Sheep

All images from Katie in Southern Oregon

Meet Charlie M., Sheep Shearer

Trimming the hooves

This is how we shear: Audrey gets a haircut

That part’s done

Molly comforts Dollie

All done

Says Katie: irls. Linda completely shed her coat. So I was interested to find out from Charlie what kind of sheep they were. He told me that Linda and Audrey are called “hair” sheep – sheep that shed their wool and don’t need shearing. Although Linda shed hers, Audrey still had most of a coat with only the neck and chest area shedding. Hair sheep are raised for their skins and meat. Their hides make the finest glove leather. They are

White Dorper sheep and maybe some Barbedos in there too as Audrey is colored, with white sox and a patch of white on her side. It is a breed originatating in Africa where it’s hot and they don’t need the heavy wool.

Charlie didn’t tell me all that as I went on the internet and looked up hair sheep, Dorper, and Barbados. I’d like to see my plumber – who I bought Linda and Aurdrey from – to get a ram so we could breed the two younger girls.

Ocean Shore RR’s “Gas Car” Stopped at Moss Beach Station

[Image below from Rosina Gianocca, via R. Guy Smith, also pictured in my book, Half Moon Bay Memories: The Coastside’s Colorful Past.]

Says Angelo Mithos:

“Hi June. I remember the Moss Beach station from one of my 1930’s trips and have a photo I took with my Brownie camera. The station was totally vacant but undamaged. Further back up the line was an OS trestle, which I also inspected (Page 120 of Jack R. Wagner’s book). Not long after, both were gone– demolished!- believe for the new highway. Re the OS’s gasoline- powered motor cars, Nos. 61 and 62. Both built at Sacramento by the Meister Co., 61 in 1918 , 62 in 1920. Each had 31 passengers. capacity. 61 had a rounded rear with observation platform; 62 had a square closed end. 61 sold to Long-Bell Lumber .Co.,; scrapped 1955; 62 sold to La Cross & Southeastern Ry.; scrapped c1934. OS bought them as an economy measure-too ezxpensive to run full size steam trains for just a few passengers. References: When Steam Ran on the Streets of San Francisco, Part IV by Walter Rice and Emiliano Echeverria; booklet Ocean Shore Railroad by Rudolph Brandt (publisher Western Railroader); The Last Whistle by Jack R. Wagner (publisher Howell-North Books). ”

June says: Rosina Gianocca told me this railroad station turned into a broom factory before vanishing from the landscape. Rosina, who grew up in Montara, got to know the Moss Beach Postmaster “Guy” Smith, who, took many fantastic photographs of the Coastside. The old historic post office still stands on the east side of Highway 1 in Moss Beach and is owned by my neighbor Connie Phipps. I hope this building will be preserved.

A Story of Coastside Newspapers

An old-new story by June Morrall

Other than their mutual interest in the 1890s Coastside newspaper business, Robert Israel Knapp and Roma T. Jackson had little in common. The older of the two, “R.I.” Knapp, was a militant teetotaler, a well-known Half Moon Bay sidehill plow inventor, with a small factory on Main Street, while Jackson, the newcomer, was a brilliant editor and no enemy of the “demon rum.”

It was the promise of a railroad linking San Francisco with the isolated Coastside—and the impact of this event—that brought the 22-year-old Jackson and wife, Francis, to Half Moon Bay. There, they founded the “Coast Advocate” in 1890.

When the first issue of the “Advocate” appeared, Jackson’s admirers cheered. “It is a neat, spicy little stranger for which we hope a long and prosperous future,” wrote the “Redwood City Tribune.”

Jackson’s compelling writing style became evident in an April 1891 piece relating a Sunday afternoon carriage ride into the famous Purissima Canyon, greatly admired for its waterfalls and giant redwood trees:

“At one o’clock, an appetizing lunch was spread on a mammoth stump beneath the towering redwood, whose waving foliage far overhead added a darker luster to the sparkle of the Champagne.”

One year later, Knapp, who possessed no special writing skills, launched the “Monthly Messenger,” designed to raise the Coastside’s standards of morality. With a printing press set up inside Knapp’s Main Street plow factory,the “Messenger” was published in the interests of Christianity and gospel temperance.

“We have something to say, and we intend saying it, publishing it not for financial profit but because we deem it necessary to be said,” vowed the editor Reverend Meese, Knapp’s son-in-law, who took his turn at the paper’s helm.

Months passed and the Half Moon Bay community was startled to learn that Roma T. Jackson had sold to “Coast Advocate” to Robert Knapp!

“The sale will no doubt change the tone of the ‘Advocate,’” ruminated observers, “as Mr.Knapp is a pronounced prohibitionist.

At that juncture, Roma and Francis Jackson may have traveled to to Southern California where Jackson founded a newspaper in Cabria, another isolated community awaiting the coming of the railroad.

After the sale, the “Advocate” editorship was turned over to physician-surgeon and medical columnist, Dr. W. V. Grimes—but his tenure was short and a man called Frank Owen soon replaced Grimes.

“While it is regretted the recent editor found himself not in touch with the people,” noted the “Redwood City Democrat,” it is hoped the new one will be more successful. The coast is able and ought to support a home paper.”

Following Frank Owen, George P. Schaeffer took over the “Advocate’s” editorship in 1897. The Schaeffer’s took their turn in the limelight when they played host to Captain Thomas Peabody and his family after the ill-fated iron ship “New York” was stranded at the foot of Half Moon Bay’s Kelly Avenue in March, 1898.

A year later the Schaeffers welcomed Francis Jackson and her children into their home. Eight years had passed since her husband, Roma, sold the “Advocate” to Robert Knapp.

“It is her intention to assist the ‘Advocate’ staff,” wrote the “Redwood City Democrat.” “Mr. Jackson is seeking a fortune in the mines of Arizona. We are glad to welcome the Jackson family among us again and are only sorry Roma T. Jackson cannot be one of us.”

Moss Beach-born writer Peter B. Kyne—a future author of national stature, whose books were best sellers and made into movies—had been penning “snappy items for the ‘Local Brevities’ column of the ‘Coast Advocate, circulation 247’”, when he volunteered to serve in the Spanish-American War, serving in the Philippines.

In 1957 Kyne recalled that each week he “faithfully sent the [Coast Advocate] editor a 2,000-word mailed story, so he wouldn’t be embarrassed by gaping holes in his paper the day the paper went to press.

“He [George Schaeffer] ran my stories under a three-column head on page one with a break-over to page two. The head was labeled, “Philippine Paragraphs,” and raised his circulation to nearly 1,700 in 14 months. Writing those 2,000 words was often a chore in active service but the editor was my friend and I never failed him, and I admit that here I first started writing fiction. But who was to prove it?”

In 1900, Roma T. Jackson reappeared on the Coastside, this time as editor of the “Peninsula Pennant,” a seven-column weekly espousing Democratic politics. The “Pennant” reported the dedication of the new 26-foot-wide Pilarcitos Creek bridge, which replaced the old wooden one at the northern end of Half Moon Bay. This was known as the “world’s first steel-reinforced concrete structure.”

The “Advocate” merged with Jackson’s “Pennant” in 1901.

Talented as Jackson was, he could not control his dark moods. After celebrating the New Year in 1903, still waiting for a railroad, the 35-year-old editor was found dead in his Half Moon Bay home. Some locals suspected suicide.

A year later 71-year-old plow manufacturer R.I. Knapp passed away and heirs took over publication of the newspaper.

Jackson’s wife, Francis, filled in for her husband at the “Pennant-Advocate” until she was succeeded by Lester A. Skidmore.

Promoting the promise of the Coastside even before the railroad’s arrival, Skidmore reported: “Quite a crowd of people were at the wharf [Amesport at Miramar Beach] to see the new passenger steamer, “Newport,” which made her initial trip to Half Moon Bay Sunday. She has ample room for all kinds of traffic that the Coastside can furnish….”

While the on-again, off-again relationship between Knapp and Jackson played itself out, one Harry Griffiths established the “Half Moon Bay Review” in 1898, according to Roy Cloud’s “History of San Mateo County,” published in 1928.

More than 20 years earlier the Ocean Shore Railroad was finally laying track near Devil’s Slide when the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire struck, sending rails and equipment plummeting into the cold Pacific Ocean. The tremors were felt in the offices of both newspapers, the “Advocate” and the “Half Moon Bay Review.”

“…the worst mix-ups were in the newspaper office,” wrote the “Advocate’s” H.G. Copeland. “All eight pages of the “Review” were pied beyond redemption and type was thrown promiscuously about the office. Two forms of the “Advocate” were pied and one rack of job type was turned over and the type, about a washtub full, had to be picked up with a scoop scovel.”

The earthquake may have brought about the “Advocate’s” last gasp. Editor Donaldson of San Francisco complained of shabby treatment given him by the Knapp estate heirs. The remaining Knapps relocated to San Jose in 1907.

Enter George Dunn. From a quaint office building still standing in Moss Beach, Dunn published the “Coastside Comet,” a quirky publication linked with news of the Ocean Shore Railroad and the new beach towns.

——

Angelo Misthos’ corrects me:

Hi June. Hope you aren’t getting overloaded with OS trivia. If so, please advise. Re your “A Story of Coastside Newspapers” (7/8/09): “More than 20 years earlier the Ocean Shore Railroad was finally laying track near Devil’s Slide when the San Francisco earthquake and fire struck, sending rails and equipment plunging into the cold Pacific Ocean.” I don’t believe the OS tracks had reached that far when the quake occurred on 4/18/06. Per Rudolph Brandt’s booklet, Ocean Shore Railroad, Pg. 7, “By September, 1907, the rails had reached Rockaway on the north end.” Jack R. Wagner, in The Last Whistle, Pg. 39, makes the same point. The OS often graded in advance of track-laying, but there seems no evidence that tracks and equipment had reached the Devil’s Slide area that early. Unless you already have it, Google: Calisphere.universityofcalifornia.edu. Click on California in Transition; in search block at right enter Ocean Shore Railway to find pictures of OS earthquake damage.The picture titled: “Ocean Shore Track (Landslide damage to Ocean Shore Railway. Unidentified Location”) shows Montara Mountain in the far distance– Pedro Point out of view at far right–and Mussel Rock(s) in the near distance. If you enlarge the track pictures you can see some ties that look either used or second quality and some that do not appear spiked to the rail and no sign of ballast–crushed rock used to stabilize the track; in short, second class work typical of the perpetually cash-strapped OS. Angelo

According to the historian/author Roy Cloud, George Dunn later bought the “Half Moon Bay Review” and the “Advocate,” merging both papers in the “Half Moon Bay Review” that we know today.

John Vonderlin: 1899: The East Coast Rich Vanderbilts Showed Interest In Coastside Railroad

Story from John Vonderlin

Email John ([email protected])

Why did the Wealthy East Coast Vanderbilt Family Want to Finance a Coastside Railroad to Compete with the Peninsula’s Southern Pacific?

Hi June,

This article, from the April 11th, 1899 issue of the “Call,” explains somewhat why the West Shore Railroad Company hadn’t yet built a track down the coast from San Francisco to Santa Cruz, despite their assertions of it being a “sure thing” in the earlier articles from 1894 and 1895 that I sent in earlier posts.

This day’s dream is that the Vanderbilts, those alleged paragons of fair play and fair prices, those East Coast “compassionate capitalists,” will be veritable “White Knights,” riding to the rescue. Success can’t be far off.

Enjoy. John

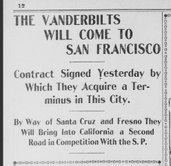

THE VANDERBILTS WILL COME TO SAN FRANCISCO

Contract Signed Yesterday by Which They Acquire a

Terminus in This City.

By Way of Santa Cruz and Fresno They Will Bring Into

California a Second Road in Competition With the S. P.

With a contract signed by their agents in New York City on the M D sth inst. the Vanderbilts have become the owners of the West Shore road to Santa Cruz. They already had control of the proposed Fresno-Monterey line, and these two systems they propose to connect with their Salt Lake-Los Angeles road, now built to Pioche, Nevada. By this combination of routes they will bring into San Francisco their transcontinental system, to work with the Santa Fe the salvation of California in bringing against the monopoly of C. P. Huntington the destructive force of pure competition and honorable business policy.

The Vanderbilts have secured ln this city a western terminal to their lately bought transcontinental railway system. By a deal consummated in New York City on the 5th of the present month they secured of Behrend Joost and his associates the rights of way and the franchises of the West Shore Railway from San Francisco to Santa Cruz via Colma and Pescadero, and for some weeks past they have had practical control of the Monterey-Fresno line from Monterey to Fresno throughthe Coast Range via Walker Pass. From Fresno a connection with the road they are now building from Salt Lake City to Los Angeles is simply a matter of laying ties and tracks.

Not alone is the Santa Fe to stand in competition with the Southern Pacificof Kentucky, and nearly every other State of the Union. Not alone is the Santa Fe to take up for the man of the hoe and the man of the mills of California the competitive fight for rates and profits and the fair living that the soil of this State should render its every tiller. Against the capital and brains of C. P. Huntington, the monopolist, are set the brains and capital of the Vanderbilts, those multi-millionaires of the East who have builded world-famous fortunes by open fighting and fair competition, and it is now no more than the time required to fill with track and prosperous stations the two gaps that exist before San Francisco will be sending its drays and its clerks to receive the cargoes hauled in under the steam of the second competing road.

The negotiations that resulted in the deal of the 5th inst. were opened some six weeks previous to the late visit of the numerous Vanderbilt parties to this coast. Simultaneous with their arrival here came a representative of the Vanderbilts’ New York agents, Freeman & Jones, of 51 Broad street, New York. Laden with the field notes of the numerous surveys that have been made, provided him by Behrend Joost, he traveled and inspected the route of the proposed road from this city to Santa Cruz. Not only did he look into the feasibility of the road itself, but he investigated thoroughly the income-producing capacity of the country which it taps.

The redwood forests that surround Pescadero and the dairies and farms, the most extensive outside the San Joaquin Valley and more fertile than they, impressed him at sight, and his favorable observations he communicated directly to the Vanderbilts during their much-written-of stay at Del Monte. Communication between them and their New York agents at once ensued. Through General W. H. H. Hart, who has long been their advising atttorney on this coast, Behrend Joost was approached and through him the rest of the West Shore Company. Joost and his confreres were in a proper state of mind to talk business on business principles. For more years than history cares to tell of it the completion of the coast road to Santa Cruz has been Joost’s annual dream. Late in ’97 he had got all of his rights of way. There were some stickers alone the route and they held out for stiff prices, but popular pressure finally had Its effect and the May was clear for a seventy-minute competing track to the seaside city. Then Joost and the company discovered either that they did not have or did not care to risk the money the road and its rolling stock would cost Quietly the deal was called off and Joost came on the market to sell his franchise. It was valuable and worth the price he asked and more. Besides the clear Tights of way about $65,000 had been expended In grading a roadbed over the most difficult portion of the proposed route, a strip of beach at Waddell Creek, twenty-two miles from Santa Cruz. Add to this the fact that the line extended from San Francisco’s waterfront at a point south of Islais Creek and out of the county by way of Colma, and ran thence to San Pedro Point and along the coast through seventy miles of the grandest marine scenery that California boasts, and Mr. Joost had probably as marketable a piece of property as could be found waiting a purchaser. But the market was timid of Mr. Joost. At the mention of his name on the street it held up its financial skirts like an old dame at a mouse. In Its prejudice it was blinded to one of its best opportunities and finally the west shore line was hawked over the streetsand offered for anything to anybody. Then the Vanderbilts got their Salt Lake line on the way to Los Angeles builded as far along as the little mining town of Pioche, over In Nevada.

Three months ago the papers told of a mysterious surveying party that had been laying out its line and driving its significant little red-topped pegs into the shifting sands of the deserts between the thirst-stricken Nevada line and the orange groves of tho southern city; and they told further of an agent, of whom no one knew or would tell, who went along ahead of them and bought up or secured rights-of-way over the country to be surveyed. All was done quietly and without ostentation. Not the cleverest correspondent could get a line on the story and it remained as much a mystery until today when back from New York came the contract that made it all as plain as day.

By its terms the Vanderbilts assume of Behrend Joost and his fellow-stockholders the entire right of way of the West Shore Railroad Company from San Franicsco’s water front via Islais Creek, Colma, Halfmoon Bay and Pescadero to Santa Cruz. In return they guarantee to grade and build the road, establish stations and equip with such rolling stock as the traffic may demand this for the present and for this end of the line.

The visit of the Vanderbilts to Del Monte, however, developed the fact that the West Shore transaction was to be merely incidental to the main proposition. They were not looking for a mere source of pastime in Pacific Coast finance, but under the guise of a rollicking pleasure trip were seeking out a western end, and a means of getting to it, to that petty hobby, recently realized, of Mr. Vanderbilt’s, his transcontinental road.

Their trip to Monterey was not so much to gather sea mosses and catch perch from the end of the one lone wharf as to inspect the dock and terminal facilities of the proposed Monterey and Fresno Railroad. Over that line the rights-of-way and franchises have also been clear and the road bandied back and forth across the market since ’96. It leads from Monterey to the heart of the San Joaquin by the most direct route, Walker Pass,and from there a connection with the Salt Lake-Los Angeles road is an easy possibility at almost any point on the desert, and, for the most part, over Government land.

Upon equally good authority it is said that the Vanderbilts have secured, on practically the same agreement, the entire line of the last named road. Between the terminal of the West Shore line at Santa Cruz and the Monterey-Fresno line, there is a gap of forty-four miles extending round Monterey Bay, which is covered by neither franchise nor rights-of-way. but the people of that section have been for so long going into debt to C. P. Huntington for their tree slips and seeds, that an easy road is open to the agent of the Vanderbilts now working in that section.

It was rumored that they were negotiating with the Spreckels people for the narrow-gauge road now owned by them from the prosperous city of Watsonville to that equally thriving burg, Salinas, but this John D. Spreckels denies, and states that he will maintain that road solely as an adjunct to the Spreckels beet-sugar interests in that locality and as an agent for the further building up of the two counties. There are two or three routes, however, other than that occupied by the Spreckels line by which Monterey or Salinas may be reached, and the agent for the Vanderbilts In this city. General Hart, anticipates no trouble in acquiring one of them.

The acquisition of Santa Cruz and Monterey as stations on their line will give the Vanderbilts an equal shipping advantage with the Southern Pacific. The two cities command the opposite boundary points of Monterey Bay, which is, even in heaviest weather, an Ideal anchorage and only a short haul from this city. The advantage will be with the Vanderbilts for the reason that their route along the coast is over an hour shorter than either of the Southern’s Pacific’s present lines and will cost, comparatively, nothing in maintenance. The contract which binds all this and makes of an airy possibility a cast iron assurance that the Santa Fe and Valley roads in their combination are to have the weight of independent millions and fair, open principle with them in their fight against the relentless and dollar-marked tyranny of the Southern Pacific. With California’s new and splendid opportunities in the Orient is to work jointly the facility of competitive transportation from the markets of the whole country and the document received yesterday puts these possibilities beyond the grasp and greed of C P. Huntington.

It was signed in this city for the West Shore Railway Company on March 25 by R. S. Thornton, the president, and by R. J. Willats, the secretary. Then it was forwarded to New York and signed by Freeman & James agents for the Vanderbilts, on the 5th inst, It guarantees to the stockholders that the New York people shall fully equip the road with modern steel bridges, track and rolling stock, and that they, the shareholders, shall participate proportionately to the amount of their stock in the only company in the new concern. General Hart, who holds the contract cannot speak to a certainty but says he is authoritatively informed that active work will be begun within the next sixty days.

Remembering the “Corral de Tierra”

A new-old story by June Morrall. [I wrote this in the 1970s when I was first learning about the fascinating Coastside. Most of my research was done at the San Mateo County History Center, then located on the campus of the College of San Mateo.]

The Corral de Tierra

Festive rodeos lasting several days were commonplace around Miramar Beach in the 1840s, the mid-19th century, pre-Gold Rush, pre-Mexican-American War.

Accompanied by merry-making and feasting, the round-ups included scores of rancheros, the Spanish/Mexican grantees to huge numbers of acreage, and the skilled performance of their “vaqueros,” or cowboys. These were special, exciting occasions where spirited competition among the vaqueros took center stage as they showed off their excellent horsemanship and remarkable use of the la reata, or the handling of ropes.

The grantee to the Corral de Tierra was Tiburcio Vasquez, among whose kids was Pablo, later considered “Coastside royalty,” and whose home stood near the quaint concrete bridge in Half Moon Bay.

Cattle picked for later slaughter were lassoed by the vaqueros; brought down and burned with the owner’s steaming hot brand. The other animals were released, allowed to roam freely for another year on the Corral de Tierra—-encompassing the present-day communities of Montara, Moss Beach, El Granada , Miramar, stretching all the way to Pilarcitos Creek in Half Moon Bay. The land was called the Corral de Tierra because its natural shape resembled that of an earthen corral or natural enclosure.

Up until 1840, Mission Dolores in San Francisco used the land for grazing. Our Coastside was an isolated territory, cut off from “civilization” by mountainous barriers, making it difficult for families and large amounts of belongings to relocate there. At the time the hills concealed a considerable mountain lion and grizzly bear population.

The Corral de Tierra was divided into two Spanish/Mexican land grants. Tiburcio Vasquez (the uncle of a notorious bandit with the identical name who was hanged in San Jose in the mid-187os) ran 2100 head of cattle and some 200 beautiful horses on his 4, 436-acre rancho. Tiburcio, the land grantee, had been supervisor of the Mission Dolores livestock when he applied and received the southern portion of the Corral de Tierra.

That left the northern 7,766-acres to Francisco Guerrero, who had held many positions throughout his official career in San Francisco. The dividing line between the two ranchos was the Arroyo de en Medio Creek the Ocean Shore Railroad-named Miramar.

Guerrero built a ranch home known as the “Guerrero Adobe,” on a hillside near a creek about one mile northeast of Princeton.

[Image of the Guerrero House, which also became Charlie Nye’s first hotel.]

Until the 1906 earthquake and fire, the house was still in fair condition, including four rooms on the ground floor with an attic above. A porch surrounded the entire front of the home.

It is said that Tiburcio built the first adobe in Half Moon Bay, then known as Spanishtown. The adobe had five rooms and stood on the north bank of the Pilarcitos Creek, northwest of the concrete bridge. (Yes, that confuses me, too.)

As I mentioned above, Pablo, the Vasquez’s youngest son who lived into the early 20th century, built a frame house that is still standing near the bridge. He opened up a successful livery business–but when the barn deteriorated over the years it was finally demolished on February 18, 1977.

Francisco Guerrero, the other land grantee, and a man with many jealous enemies, continued to spend a great deal of his time in less isolated San Francisco. In 1850 he was murdered as he stood near the corner of Mission and 12th Streets. The fatal injury occurred when a mysterious man on horseback struck him about the head with a slingshot.

And on April 12, 1863, as Tiburcio Vasquez sat near a window in a Spanishtown saloon, a volley of gunshots rang out. When the dust settled, Vasquez was found dead—and the elusive murderer long gone.

According to informed observers, both Vasquez and Guerrero were significant witnesses in the “famous” Santillian land fraud case. Some speculate that this connection led to both their murders.

Ad for Levy Brothers

Good Information for Coastsiders:

If you need to reach the local police, and you are in your home, do not use the cell to dial 911 because you will reach the CHP (California Highway Patrol) which will delay the message to the local police.

Always use your hard line to call 911 when you are in your home. The local police will respond faster.

John Vonderlin: What did the Coastside look like to the earliest cartographers?

Story by John Vonderlin

Email John ([email protected])

Hi June,

While I was researching the next of the early Coast Survey maps I wanted to post about, that being the Half Moon Bay one, it occurred to me there must be some much earlier, cruder maps showing the Coastside, then the meticulously documented ones the Coast Survey created. The Library of Congress had a few interesting ones I’d like to share.

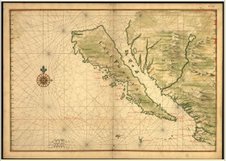

The most unusual thing about the early maps was they showed California as an island. Based on inaccurate Spanish accounts, European cartographers had begun in 1622 to portray the western coast of North America as a seperate island. The British and Dutch accepted this misconception well into the 18th century, long after Father Eusebio Kino confirmed during explorations of the American southwest from 1698 to 1701 that California was not an island.

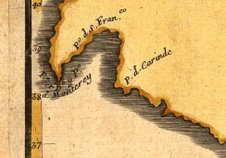

This first map, published by Joan Vinckeboone, a Flemish cartographer, in 1650, illustrates that. I’ve attached a close-up of the Coastside from this map, though it is recognizable only by its relationship to Monterey and Point Reyes.

The next map is from 1720 and it’s not much better, though as you can see the details in the Mexican mainland are much improved. This was created by Nicolas De Fer, a French cartographer. The close-up of the Coastside and surrounding area is even less recognizable in this one.

The quality of these maps, as far as portraying our area accurately, gives us a good idea why Portola, in 1769, found it so hard to find Monterey, and passing it by, eventualy making the serendipitous discovery of the San Francisco Bay. Enjoy. John