This Tiburcio Vasquez operated in the San Jose area. See his story below John’s post.

This Tiburcio Vasquez operated in the San Jose area. See his story below John’s post.——————-

Hi June,

The Secessionists were attempting to keep California out of the Civil War. Mr. Denniston was quite the character, possibly one of the most colorful residents ever of HMB. Here’s a little excerpt about California secessionists.

I’ve got this strange article about Denniston, crime, political office, etc. I’ll send next. Enjoy. John

When the news of the threatened Civil war reached California, the southern wing of the Democratic press sneered at the idea of any war and declared the reports untrue. During the time that they were denying the reports of war, their friends were secretly planning to secede. When the fact was undeniable that war existed, then they began abusing the government. The majority of the Democratic press took good care to keep within the bounds of martial law. The San Jose Tribune, San Joaquin Republican, Stockton Argus, Visalia Expositor and Merced Express abused the government and the United States troops. They were excluded from the mails by the orders of General Wright and thus suppressed [16].

During the war this press continued its abuse, and it culminated April 15, 1864, in the destruction of several San Francisco offices by a mob. When the news was received of the assassination of President Lincoln, on the morning of April 15th about 8:00 o’clock, it created intense excitement throughout the loyal state. In San Francisco a body of men rushed to the Democratic Press and smashed things generally, and ended by throwing all of the type out of the window. The crowd howled. Beriah Brown, the editor, started hurriedly for San Leandro. The police dispersed the crowd, but again forming they served the Catholic religious paper, the Monitor [17] as they had served the Press. Then followed in turn the News Letter, edited by the Englishman Frederick Marriott, and the Occident, published by Zacharaih Montgomery, one of the bitterest secessionists in the state. Burning the printing cases of these papers in the streets, the mob started on the run for the office of the French paper, the Echo de Pacifique. The Alta, owned by Fred MacCrellish, was in a part of the same building. MacCrellish succeeded in pacifying the mob and thus saved a part of the French paper. The police now succeeded in driving back the mob and soon after General McDowell put the city under martial law and United States soldiers guarded all of the streets.

—————————-

[Note: There be errors in the text. Not to worry.]

More About James Denniston

There are some respectable people in San Mateo county. That’s so, notwithstanding the character of a few of the men who have represented them of late in the Legislature, the Supervisors, and the Union Convention. There are some men who have never been intimate friends with Ned McGowan and Bill/ Mulligan. There are some men who do not believe in ballot-box staffing. There are some men who do not believe in taking valuable public property, and giving it to favorites, without reason. These are facts. It is not strange, therefore, that some people in San Mateo county are not altogether pleased with Mr. Denniston’s conduct in the Toll-Road affair. The only paper of the county, and it is sound on the Union question, is bitterly opposed to Mr. Denniston. So are most of the people who live along the San Jose road, from San Mateo to Redwood City, and San Francisquito; and they are the bulk of the people of the county. So strong was this feeling, that Denniston’s friends saw that they conld not carry the county, at the late Union primary election for a County Nominating Convention. The enemies of Denniston elected nearly all the delegates. Bnt Denniston wanted to be Senator. He wanted to have three delegates favorable to him elected to tie Joint Convention, by the San Mateo County Convention. The latter Convention was opposed to him. He conld not get the three delegates fairly. It was necessary, then, to resort to foul means. The old County Committee of San Mateo, elected before his Toll-Road legislation, were his servants. They demanded the right to examine the credentials of the County Convention. The demand was absurd. It was contrary to all usage and reason. Every deliberative body examines its awn credentials. All Legislatures, and all Conventions do, and have done so, from time immemorial. , No State . Convention has ever permitted ‘ a State Central Committee, no County Convention has ever permitted a County Committee, to decide on the qualification*- of its members. However, Denniston did not care about the custom, the right or the reason. ., He knew that the Rowdy Convention of San Francisco would do anything | for him if they only could obtain an excuse for acting. If any San Mateo delegates, in Denniston’s interest, would only claim seats in the-‘ Joint Convention, they would obtain them. J The Rowdy Convention, and its Hero, James G. Denniston. The Lotaltt of Calikobn-ia. — A New York paper, speaking of California, says: ” The loyalty of California to the Union has ” been preeminently a loyalty of the afiiec” tions. Had California chosen to break ” the ties which bind her to th« republic, it ” is not easy to estimate the extant of the ” damage which her defection must have in” dieted upon the nation ; unless, indeed, by ” a standard of contrast with the immense ” strength, as well moral as material, which “her loyal adhesion to the Union and the ” Constitution has contributed to the com” mon cause.” Let the above tribute be fully sustained to-morrow by the triumphant return of the Union State Ticket and the Union Independent County Ticket. Be active, untiring and vigilant. Denniston is not the worst of men, nor the wont man on the Rowdy ticket. He is a jovial companion, a good judge of horses, a connoisseur in whisky, and a good specimen of a ” fast man ;” but he is no speaker, he knows nothing of Parliamentary tactics, and he cannot have the least influence in a Legislature. There are ether men on the ticket who are less honest, less scrupulous, more able, and more dangerous by far to legislation, than Denniston. DennUton had a few men in the San Mateo County Convention. When the Convention refused to let the Committee examine their credentials, the Denniston men withdrew, organized a Convention of their own, chose their delegates to the Joint Convention, and nominated their county ticket. The regular Convention’ did likewise. The two sets of delegates, the one in favor of Denniston, the* other opposed to him, appeared before the Joint Convention. The case was perfectly plain. On the one side were universal custom, reason, decent public sentiment, and the great body of the Union voters of San Mateo county; on the other were Mr. Denniston, Mr. Joseph Ames, [who, as Supervisor, encouraged Denniston in the Toll-Road business,] and all the interests of rowdyism and ruffianism. The latter cause won the day, and had a glorious triumph. The Denniston delegates were admitted; the Joint Convention nominated Dennigton first of all ; he was their ideal of a man. And this is the Convention, which is held up with its nominations, as sacred. When such things become sacred in San Francisco, then decency and honesty ought to be and will be proscribed.

================

James G. Denniston and the San Mateo Toll Road

By these explanations made openly upon an exciting question in the Legislature of California, Mr. Denniston was publicly accused of having secured the passage of the bill by misrepresentation. He never denied the truth of the statement of either Hathaway or Shannon. In such cases, it is expected that a member of the Legislature will at least rise to a question of privilege and vindicate himself, but Mr. Denniston never did it. The bill was denounced as a fraud by many Senators and Assemblymen in open session. Nobody in either branch of the Legislature said a word in favor it, after its character had been exposed. Its author remained silent The Assembly unanimously passed a resolution requesting the Governor to erase his signature; the Senate refused to pass the resolution, for no reason save that they denied the right of the Governor to erase his signature from an act once signed. —[See Alta of March 27.] The Legislature afterwards passed an act to interpret the Toll-Road act, and to render it of no avail for the purposes designed. This supplementary act (it may be found on page SCI of Statutes of 1863) is really a repeal of the other, and effectually killed the fraud designed. It passed witheut opposition. Nobody attempted to vindicate the first bill or Mr. Denniston. The two acts stand as a monument of Mr. Denniston’ s fitness to be a Senator. ” Mr. Shannon said he had moved that the bill pass, at the request of Mr. Denniston, the Assemblyman from that County, who assured him that Dr. Hathaway wished him to move an immediate passage under a suspension of the rules, so soon as the bill should come in from the Assembly. In accordance with that request, be made the statement of Mr. Denniston to the Senate, and made the motion under which the bill passed. He knew nothing and cared nothing for the bill, and did no more for Mr. Denniston than he would have done for any other person. The question was now one between Dr. Hathaway and Mr. Denniston. ” Dr. Hathaway said he had never authorized Mr. Denniston to make such a Jequcst or statement.” The next day Senator Wallis, who had been out at lunch when the bill passed, denounced it, and Mr. Shannon and Dr. Hathaway explained. The Sacramento letter, published in the Alta of the 26th March, contains the following report of their explanation : The idea of granting such a franchise would be outrageous under any circumstances, but this bill proposed to take the property of the county without the consent of her official*, or the knowledge of her people. The matter was kept a secret until the bill had passed. The consent of the county officials could not have justified, though it might have furnished some excuse for the bill. The father of the bill was James O. Donniaton. He introduced it ; as the only Representative of San Mateo County in the Assembly, and claiming to represent the wishes of his constituents truly, he secured its passage. It was ” a little local bill,” and the Assembly trusted to the honor of the local Representative. They passed it in perfect blindness and ignorance of its nature. In the Senate the only Representative of San Mateo County was Dr. Hathaway. During his absence, Mr. Denniston took the bill, after its passage in the House, to Senator Shannon, and said Dr. Hathaway wished him (S.) to move a suspension of the rules, and pass the bill. Such requests are not rare, and Mr. Shannon had no reason to suspect any ill faith about the matter. He knew that the bill had passed the Assembly, and presuming that all was right, he made the motion. The bill was passed, and the Governor signed it on the 24th of March, before he knew its meaning. One of the most outrageous frauds ever proposed in the Legislature of California — and that is saying a great deal— is the act to grant to James E. Kuttman and others the San Francisco and San Jose road, so far as it runs through San Mateo county, for a toll road. The act may be found on pages 99 and 100, of the Statutes of 1863. The road was and is the property of the county. It is the chief county road of San Mateo, and the only wagon road by which travelers come to San Francisco from Santa Clara County. San Mateo has spent many thousands of dollars upon the road, and it is in excellent condition during nine months of the year. The act was drawn for the purpose of giving that road to Xuttman and his associates, with the right of erecting toll gates— the number is not specified— and collecting 25 cents for a horseman, 60 cents for a two-horse team, and $1 for a four-horse team at every gate. The grantees were required to grade the road, and since the road was already open, the earth soft, and the land level most of the way, the grading might have been done for $6000. In return for that, the grantees were to have the privilege of collecting about $30,000 annually of tolls upon the only road leading into San Francisco, for twenty-five years. James G. Denniston and the San Mateo Toll Road.

——————————————

The story of Tiburcio Vasquez, the bandit (who had the same name as the Coastside ranchero)

A new-old story by June Morrall (I wrote this years ago, please don’t hold it against me!)

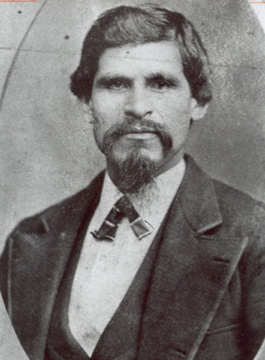

Tiburcio Vasquez, the Notorious Bandit

Although Tiburcio Vasquez spelled his name exactly as the founding father of Spanishotwn –which we know today as Half Moon Bay, probably due to the United States Geological Survey’s (USGSS) description of the bay that looked like part of a circle–this Tiburcio Vasquez was a famous 19th century bandit who little resembled his law-abiding uncle, the Coastside owner of a huge rancho.

According to local legend, the bandit lived in Half Moon Bay in the 1850s, and the resident Joseph Miramontes said he could never forget meeting the “wild, mischievous boy” on the Rancho Corral de Tierra belonging to the law-abiding uncle.

But while the bandit Tiburcio earned himself a notorious reputation in the eyes of the new Americans–who began to appear after the Gold Rush–he had his admirers, native Americans” who applauded his exploits and infamous deeds, To some, he was compared to Robin Hood. Poets dedicated sonnets to him, women fell head over heels in love with him, and kids aspired to be just like him.

When asked, Vasquez, the bandit, explained that following the Mexican-American War (1846-48), a wave of discrimination followed, thus his criminal behavior. The big changes, brought to light by the sudden influx of Amerians, was difficult to cope with, a clash of cultures, so to speak.

In further explanation, he pointed out that at the traditional California balls and parties, Vasquez rubbed elbows with “rude” Americans who shoved aside the native men and “stole” their women. This brought about a strong feeling of revenge and the very young bandit Tiburcio Vasquez headed up a gang that stole horses, robbed stagecoaches, and caused general havoc.

What little we know about Tiburcio is that he was born in Monterey in 1935, well before the 1849 California Gold Rush.

Here’s the rest of his “story”: Tiburcio was a troubled young man who soon fell in with Anastacia Garcia, a well known horse thief and bandit . According to legend, Garcia belonged to the infamous Joaquin Murietta gang.

While Garcia attended an entertaining “fandango,” in Monterey with Vasquez, friend Garcia incited a brawl that grew and grew. Constable William Hardmount arrived to to restore order but was murdered forcing Garcia and Vasquez to flee into the nearby mountains.

It didn’t take long for a posse to pick up Garcia, and return him for trial in Monterey. He never made it into a courtroom as angry vigilantes stormed the jail and hung him. Vasquez escaped, robbing even more stagecoaches and staging hold-ups.

Eventually he headed for Southern California where he was arrested with Juan Soto, another criminal dubbed “the human wild cat.” Soto was killed in a famous gunfight with the well known California lawman Henry Morse. Tiburcio Vasquez was sentenced to San Quentin for five years. But as soon as he could he escaped during a “general prison break,” was caught for stealing horses again, and sent back to jail.

Tiburcio never gave up his career path, and when he got out of prison he continued in the same vein, but he had a partner called Tomas Redondo, described as tall and handsome. He also had aliases including “Procopio” and “Dick of the Red Hand,” whose life of crime was also ended by toughSan Francisco Sheriff Morse.

Eyewitnesses said Tiburcio operated in both Alameda and Sonoma Counties before returning to San Quentin for a third time.

This time when he was released he joined up with Cleovaro Chavez, a 5’11” 200-pound fellow. For five years Chavez and Tiburcio joined forces committing major raids on farms and ranches and robbing anyone who was vulnerable. The pair also had complicated love lives, leading to secret affairs with each other’s wives.

By now Tiburcio Vasquez was a brazen criminal, unafraid and willing to take huge risks. He knew what to expect from the sheriff and he had leanred to make the perfect right moves. He had become hard to catch.

Following the successful robbery of 12 people in a San Joaquin River town [where Tiburcio revealed a kinder side of himself by returning a stolen watch to his owner]–Vasquez schemed to rob and derail the Southern Pacific payroll train running between San Jose and Gilroy. But this risky plan failed. And to make up for the disappointment the Vasquez gang robbed a nearby hotel instead.

Tiburcio Vasquez, the bandit, had reached “robber-star” status and the press loved covering his exploits, perhaps even adding their own exaggerated flourishes to their stories. Vasquez’s exploits sold papers.

For example, a gunfight he was part of became a big story due to the shoulder wound he received, and without first-aid, rode away from the scene for at least sixty miles before stopping to have the painful wound examined.

He became a folk hero to native Mexicans who often offered him temporary refuge. Vasquez developed the clever idea of a vast spy network to warn him, and he developed mutual pacts of protection. Remember, we’re talking about the times around the “Mexican-American” War and its aftermath.

On at least one occasion, when “officials” stumbled across one of Tiburcio’s mountainous retreats, he slipped away, and the people who lived in the town at the bottom of the mountain claimed no knowledge of the bandit. His life consisted or running from one place to the next hoping not to be caught.

On another occasion, and what evolved into a “Black Swan” moment, that is an unexpected event, while the Vasquez gang were robbing a stagecoach they recognized a passenger they knew well, and ended up letting everybody go.

….more to come…