Story by John Vonderlin

Email John: [email protected]

Hi June,

Here is a followup article about the San Pedro road modernization and realignment from the June 1937 issue of “Highways and Public Works.” that I sent you previously. It appeared in the December 1937 issue.

OCEAN SHORE HIGHWAY JOB IS COMPLETED

On Armistice Day November 11th, 1937, one of the most difficult highway construction projects, and probably the most important section of the so called, “Ocean Shore Highway,” between San Francisco and Santa Cruz, was opened to public travel.

District Construction Engineer E. G. Poss, in an article appearing in the June 1937, issue of this magazine, briefly described the nature of, and a few of the construction problems on this project. Accompanying the referred-to article was a sketch map showing the alignment, and a photograph of the former county road with its 250 curves, and 42.2 complete circle-turns in its 10.6 miles of length, with a total rise and fall of 2,409 feet.

The importance of this portion of the Ocean Shore Highway, commonly referred to as the “Pedro Mountain” section, was aptly portrayed by the twenty-eight curves involving only 3.8 circle turns and 1,225 feet of rise and fall of grade in the new 5.9 miles covered in this construction project.

TIME AND DISTANCE SAVED

TIME AND DISTANCE SAVEDThe savings of 4.7 miles in distance does not truly reveal the convenience afforded the traveling public afforded by this new road. The former road, in practically its entire length, gave no sight distance to the motorist, who, in averaging fifteen miles per hour, throughout the entire length, was making good progress. The highway will permit progress throughout its entire length speeds averaging close to the legal speed limit of 45 miles per hour, and will effect a saving in travel time more then one-half hour to all motorists destined to south of Farallone City.

This highway will therefore assume great importance, not only as a recreation road between San Francisco and the beaches and redwood-covered slopes of the Santa Cruz Peninsula, but also an market artery in the transportation of truck garden, dairy, and stock-raising products of the rich agricultural area centering around the coast towns of HalfMoon Bay, Pescadero, Tunitas and San Gregorio.

SCENIC HIGHWAY

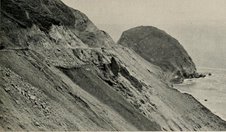

The scenic nature of the new highway is portayed by the cover-page photograph on this magazine, which shows it to be comparable in this respect to the newly-opened Carmel-San Simeon scenic coast route.

The scenic nature of the new highway is portayed by the cover-page photograph on this magazine, which shows it to be comparable in this respect to the newly-opened Carmel-San Simeon scenic coast route.From a construction standpoint, the project involved one and one-half million cubic yards of roadway excavation, or an average of one-quarter million cubic yards per mile. These quantities include approximately 700,000 cubic yards of material removed outside the original typical roadway section, principally slides occurring at the famous “Devil’s Slide” on Pedro Mountain, near the center of the project. Some daylighting of small cuts was included at vantage points, to give the motorist full advantage of the marine view, and to increase the sight distance as a safety precaution.

Rubble masonry walls played an important part in retaining the roadbed at control points on the steep mountain slopes. These were constructed in preference to concrete walls, due to the availibility of rock, from the standpoint of economy of construction, and also to keep the nature of the improvement in line with the scenic features of the rugged coast country traversed. Approximately 700 feet of lineal rubble masonry parapet walls were constructed on top of the masonry rubble retaining walls supporting the roadbed, a job itself. As is so common in the north coast section of northern California, where all formations have been shaken and disturbed in earthquakes in the past, providing stability of the roadbed calls for the solution of more difficult problems in the construction of large fills then it does in excavating the material from large cuts. The present project presented a problem in the construction of a fill approximately 85 feet depth at the centerline, involving approximately 100,000 cubic yards of material in place.

Rubble masonry walls played an important part in retaining the roadbed at control points on the steep mountain slopes. These were constructed in preference to concrete walls, due to the availibility of rock, from the standpoint of economy of construction, and also to keep the nature of the improvement in line with the scenic features of the rugged coast country traversed. Approximately 700 feet of lineal rubble masonry parapet walls were constructed on top of the masonry rubble retaining walls supporting the roadbed, a job itself. As is so common in the north coast section of northern California, where all formations have been shaken and disturbed in earthquakes in the past, providing stability of the roadbed calls for the solution of more difficult problems in the construction of large fills then it does in excavating the material from large cuts. The present project presented a problem in the construction of a fill approximately 85 feet depth at the centerline, involving approximately 100,000 cubic yards of material in place.Within a length of 400 feet along the roadway, it was necessary to strip approximately 4,000 cubic yards of unstable top soil, and to excavate trenches twelve feet in width, and up to 20 feet of depth, involving approximately 12,000 further cubic yards of excavation.

These trenches, consisting of one transverse, two longitudinal, and one diagonal ditch, explored the natural drainage courses of a number of underground springs, and were led into one outlet trench and backfilled with large rock placed directly on the supporting rock, to insure the free drainage of the entire area beneath this important fill. Approximately 9,000 cubic yards of rock were placed in these trenches prior to the starting of construction on this fill.

Another special construction problem of providing a stable roadway was presented at a location where the typical section lay almost entirely in excavation. The roadway section, for approximately 150 feet in length, was trenched into the mountain side, but the slopes down the roadway were so steep and were of such unstable material that it was considered necessary to excavate to a maximum depth of up to 40 feet below grade on the lower side, to trench the mountain slopes and carefully rebuild the fill to grade, entirely out of large rock anchored into a stable portion of the mountainside.

Another special construction problem of providing a stable roadway was presented at a location where the typical section lay almost entirely in excavation. The roadway section, for approximately 150 feet in length, was trenched into the mountain side, but the slopes down the roadway were so steep and were of such unstable material that it was considered necessary to excavate to a maximum depth of up to 40 feet below grade on the lower side, to trench the mountain slopes and carefully rebuild the fill to grade, entirely out of large rock anchored into a stable portion of the mountainside.In spite of all the precautions taken from an engineering standpoint to provide a stable roadway, as free as possible from major slides both in cut and fill sections, it is anticipated that considerable trouble will be experienced by our maintenance forces in the next two or three winters, in keeping the roadway clear of minor slides and the natural sloughing of material from the steep mountain slopes.

The maximum slide occurring on this project during construction broke on a point about 600 feet (measured horizontally) and approximately 500 feet (mesured vertically) from the grade of the roadbed. At this same point, the roadbed is approximately 330 feet above the ocean waters, with a slope below the road to the ocean.

The maximum slide occurring on this project during construction broke on a point about 600 feet (measured horizontally) and approximately 500 feet (mesured vertically) from the grade of the roadbed. At this same point, the roadbed is approximately 330 feet above the ocean waters, with a slope below the road to the ocean.Granfield, Farrar, and Carlin were the contractors, H.A. Simard was the resident engineer for the State on this project.