A new-old story by June Morrall

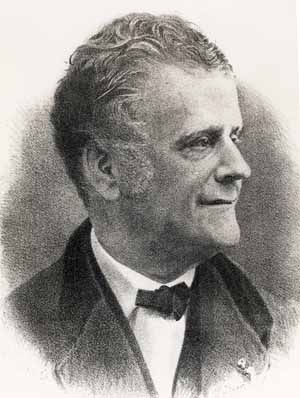

[Image below: Frederick Marriott]

Frederick Marriott & His Flying Machine

[Note: Frederick Marriott came to San Francisco from England propelled by dreams of gold and flying. Failing at the former, he turned to the latter, launching his dreamship, the “Avitor Hermes,” in 1869 in San Mateo County.]

The skies were clear and spirits high 138 years ago when shareholders with Aerial Steam Navigation Company gathered near Shell Mound Park–where Broadway in Burlingame is today–for the test flight of the Avitor Hermes.

In this age of hydrogen-filled balloons the Hermes was a technological leap forward, cigar shaped and equipped with a steam engine.

Invented and built at the San Mateo County Avitor Works, the Hermes was aviation pioneer Frederick Marriott’s entry in the world’s race to tame the skies for fun and profit.

Marriott zealously believed that the future belonged to steam-propelled, lighter-than-air-craft, despite the emphasis in London, Paris and Berlin on designing heavier-than-air flying machines.

So confident was Marriott of his invention, that he had raced its development against completion of the transcontinental railroad, linking the West and East coasts.

Born in 1805 in Enfield, England, Marriott witnessed the Industrial Revolution’s scientific and engineering breakthroughs, revolutionizing everyday life. The Age of Scientific Wonders captivated people, and they embraced the outpouring of inventions, including the amazing steam engine.

In his youth, Marriott traveled from England to India as an employee of the East India Company. Upon returning to his native country, his wealthy wife made it possible for him to invest in various enterprises, most of which failed. Finally he settled on a journalism career, helping launch the “Illustrated London News,” known for its graphics of the latest scientific advances, including mechanical balloon inventions.

By the 1840s Marriott’s vision of flying contraptions had reached the realm of science fiction. Equally imaginative were the names of his fanciful air carriages: “Blazing Comet,” “Lively Sal,” and “High Flyer.”

Almost religious in his fervor to conquer the sky’s highways, he boasted of future aircraft delivering mail and and passengers from San Francisco to New York–and ultimately to all the great cities of the world.

His tenure at the “News” probably put him in contact with two British aeronautical historical figures: civil engineer William Samuel Henson and inventor John Stringfellow. As proprietors of the Aerial Transit Company, they were experimenting with heavier-than-air flying machines. In the capacity of stockholder and publicist, Marriott joined the company,but one year later the two inventors bought him out.

In 1843 Marriott viewed an unofficial exhibition of the Ariel, William Henson’s model steam-driven “aeroplane,” propelled by two six-bladed pusher air screws at London’s Adelaide Gallery, where scientific experiments were conducted. Enveloped by a cloud of steam, the Aerial reportedly stunned observers who watched the flying machine roll along the ground and take off into the air. But experts declared the trial indecisive: problems with the model’s power-weight ratio left anxious sky- watchers to await the next episode in the conquest of the air.

Marriott’s flying machine “mania” was next nourished by an astonishing aviation exploit published by the “New York Sun” in 1844, which announced the balloon, “Victoria,” had crossed the Atlantic Ocean in three days.

Only later was it revealed that the “New York Sun’s” newspaper report was pure fiction, deftly blended with scientific data. The “Balloon Hoax” was the creative work of soon-to-be famous author Edgar Allan Poe.

Though filled with dreams of flying his own machines, Marriott sailed for San Francisco via Cape Horn to dig for gold. Instead, he succeeded as a banker, providing real estate loans out of a tent -office in San Francisco. He used profits to finance the building of his own lighter-than-air steam-powered balloon.

Closing down the banking business, Frederick Marriott fell back on his journalistic talent, founding the quirky “San Francisco News Letter” in 1856. Originally a sheet of blue paper, with news items on one side, the “Letter” had one side blank for pioneer San Franciscans to correspond with their relatives worldwide. The novel ideal brought him immediate success.

In the 186os Marriott’s “News Letter” announced the formation of the Aeronautical Society of Great Britain, an organization welcoming him as a member.

Although the Society favored heavier-than-air flying machines, Marriott kept focussed on developing a gas-filled fantasy air carriage.

Marriott’s longtime love affair with flying machines finally changed from a dreamy vision to an actual model in 1866. In his Avitor Works building near Ansel Easton’s Shell Park Course, the cherubic Marriott proudly inspected the the lighter-than-air machine created by his engineers.

He dubbed the craft the “Avitor Hermes,” probably named for the mythological Greek god of science and patron of science. When perfected, Marriott felt certain the small steam engine would lift the “stately little fellow” 120 feet off the ground, propelling it forward at speeds of 100 miles per hour.

Drawing on his public relations skills, he used the News Letter to publicize his invention. One gimmick was a page devoted to futuristic “Avitor Literature,” Marriott’s version of science fiction. He fantasized air carriages cruising the skies from New York to Hong Kong to Jerusalem and Baghdad, encountering and ducking all kinds of atmospheric dangers.

His “Letter” drummed up support for the Hermes, including that of Belmont banker William Ralston.

Weather and technical problems forced postponement of the gaseous craft for three years, although in 1867–to keep interest alive–Marriott gave a “San Francisco Bulletin” a peek at the Hermes. The reporter described a “hybrid between a fish and short-billed, short-necked, plump bird stretched out in the act of flying. The outlines and general features are as unlike the sketches and caricatures that have been put out as a crab is unlike a quail…”

After the reporter’s visit, the design changed to resemble what many defined as a 37-foot-long cigar shaped balloon, inflated with hydrogen gas. A ribbed propeller, not unlike that of a steamship, pushed the machine ahead while a rudder steered it.

With problems resolved, Marriott set new dates for private and public showings of the patented Hermes, but he was to suffer great disappointment on May 10, 1869, when the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads joined rails, snuffing out his dream of upstaging that historic event.

Nonetheless, on July 2, a nearly windless day, Aerial Steam Navigation Company shareholders rode the San Francisco-San Jose Railroad to the Millbrae station in San Mateo County. From there, buggies escorted the men a mile-and-a-half to Shell Mound Park.

At the appointed time, Hermes floated out of the Avitor Works and across Ansel Easton’s Shell Mound Park to the center of the field. The two-bladed propellers powered up and the hydrogen gas lifted the Hermes slowly into the air. Two men, standing fore and aft, held lines fastened to the Hermes–preventing the balloon from floating away–and followed the craft around the track at a dog trot. The performance, said to have covered approximately one mile, at 5 mph was accomplished twice.

Marriott’s “San Francisco News Letter” trumpeted the successful Hermes flight.

Two days later Marriott had to demonstrate the Avitor Hermes could perform again, this time in front of 100 viewers at Shell Mound Park. But stiff breezes deemed an outdoor exhibition impossible, so the craft was brought back inside the Avitor Works where the Hermes was powered up and rose off the ground.

The “New York Times” pointed out that the Hermes had demonstrated its inability to steer into or against the winds. Yet there was “germ of success” since the machine rose in the air and was propelled forward and backward.

The “San Francisco Daily Alta” exuded disillusionment, believing the source of power insufficient and the present affair hopeless.

In late July, the Hermes was exhibited at San Francisco’s Industrial Pavilion where thousands of school children paid ten cents each to view the air carriage rise above the floor.

Then, in a tournament, Marriott changed his mind about the feasibility of steam-powered, lighter-than-air balloon craft. In the 1880s he announced plans to build a 150-foot long, heavier-than-air flying machine called the “Leland Stanford,” and slated a future test flight from Woodward Gardens in San Francisco to Menlo Park. Marriott’s application for the new patent was turned down on scientific grounds.

The Avitor Hermes, built at San Mateo County’s Shell Mound Park, was consumed by a fire in San Francisco, according to extensive archives at the San Mateo County History Museum in Redwood City.

Frederick Marriott died in San Francisco on December 16, 1884, never fully realizing his dreams of conquering the air. Some say Marriott remains an unrecognized aviation pioneer, inventor of a steam-driven aircraft which made successful flights in California 34 years before the Wright Brothers legendary event at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina.

….more coming….