here’s his version of what happened.

To read Leonard Stegmann”s “The Signing” Click here

Good Looking Succulent

1968: Whole Earth Catalog is Born

I wrote this in 1999

By June Morrall

Story by June Morrall

Menlo Park: 1968. The first issue of the Whole Earth Catalog caught the moment. People tingled at the prospect of man’s walk on the moon, and the over-size black catalog cover art-work captured that anticipation with its memorable photo of our world taken from the heavens revealing Spaceship Earth.

By 1971 the Catalog was wildly successful, and that same year, its creator, Stewart Brand, shocked readers by pulling the plug and closing it down.

“I was exhausted,” Brand explained in an email, “and I wanted to see what would happen when you just stop a success in midstride.”

In the late 1960s if you were building a geodesic dome, fascinated by how windmills work or repairing a small gasoline engine, the Whole Earth Catalog was required reading.

Subtitled “access to tools,” the Catalog lured readers into newsprint pages filled with book reviews, accompanied by photos, sketches and diagrams on subjects as diverse as the inhabitants of the planet.

Aimed mostly at young adults, the broad range of information gathered a loyal following, some of whom submitted their own reviews and articles.

A graduate of Phillips Exeter Academy and Stanford University, Stewart Brand, a self-styled social sector entrepreneur, described the original non-profit startup catalog as a do-it-yourself of all kinds.

If Brand was the entrepreneur, the catalog’s guru was the visionary R. Buckminster Fuller, perhaps best known for his invention of the geodesic dome, an architecturally challenging structure. The catalog gave popularity to the dome as young hippies erected the unorthodox creations in remote areas, often without building permits.

Fuller, who coined the concept “Spaceship Earth,” recently had his blueprints, papers and videotapes acquired by Stanford University. He believed that information should be shared with everyone for the benefit of society, a creed shared by the Whole Earth Catalog. No surprise that Fuller remains synonymous with Brand’s famous publication.

The Catalog brought about a renaissance, explained Dan Rosset, a Redwood City woodworker, who has kept a complete collection of them. He considers the Whole Earth Catalog an educational publication filled with new ideas.

“It provided the access to tools,” Rosset said, “and by tools, I don’t mean hammers and pliers–tools are a way to access information. It exposed readers to ideas which were later brought to the masses.”

The Catalog was often portrayed as a resource for the counterculture hippies living in rural communities, but Brand insisted it was not primarily a back-to-the-land publication.

Carol Goodell, who contributed book reviews to the original catalog agreed. “It was a way to do you own research and teach yourself. The catalog blurred the lines between vocational and formal education,” said Goodell, a Stanford Ph.D, and former teacher who when this story was written in 1999 operated Carol Goodell & Associates, a San Mateo-based counseling service for college applicants.

Goodell pointed to the cultural revolution that took place in the late 1960s. “The Vietnam War, women’s liberation and the civil rights movement, combined with the excitement of space exploration, all brewed to shake the foundations of society.”

Staid Ivy League colleges were going co-ed. All educational institutions offered innovative programs to attraction non-traditional students. The profile of the average student was changing, with many of them now adults.

Enter the non-profit Portola Institute in Menlo Park. It provided support and seed money to alternative educational projects, such as Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog.

Goodell and her partner in “Real World Learning, Inc.”–came to the attention of the Portola Institute at the same time Brand was starting up the Whole Earth Catalog. They were aware of her work in the field of education, including her development of role-playing games for elementary and high school teachers that took the partners from coast to coat conducting seminars. Her anthology, The Changing Classroom, had just been published–a path-breaking effort–and Brand wanted her to write book reviews for the Catalog.

Goodell reflects on an early meeting with Brand when he asked her opinion about a new book in the area of education. After a spirited exchange, he said: “Now sit down and write what you just told me.” Thus began Goodell’s work as a reviewer for the Catalog.

Goodell was older than most of the other people employed at Whole Earth. Her husband worked for IBM and they had two young children.

In 1999 when this story was written, Carol Goodell was in her 60s. As she looked back to those early days at the catalog, she admitted she might have preferred straight-laced corporate types. About the people she worked with, Goodell said: “We had common educational values but different life experiences.”

In other words, she was straight and they were hippies.

Yet, within the Portola Institute’s think-tank atmosphere, everybody was interesting and there was a strong work ethic, although some of the people were off the wall. It was a place where a lot of ideas were flying around with great passion.

Carol Goodell summed it up: Whole Earth “was a place for lovers. Everybody loved what they were doing.”

Asked about Stewart Brand, she said he looked as if he should be wearing a yachting cap. He was the leader, he thought self-teaching was important and he was way ahead of the times.

Overseeing the Portola Institute was Dick Raymond, a former Stanford Research Institute employee. Goodell recalled this important figure as a handsome, sun-tanned fellow, a twinkle in his eye, with a nice mix of compassion, enthusiasm and realism. Raymond’s role was to ferret out the most doable ideas.

He possessed the talent to recognize other people’s abilities, Goodell said. He could repair the plumbing and teach you how to negotiate a contract.

It was Raymond who identified the promise in Brand. But they were unable to come up with the right project until Brand hit upon the notion of an “access catalog.” A good listener, Raymond peppered Brand with questions such as “Who’s the audience? How much will it cost? Where will it be distributed?” Brand didn’t have all the answers, but he knew he wanted to call it the Whole Earth Catalog.

The Catalog was launched at 558 Santa Cruz Ave in Menlo Park, a comfortable suburb near Stanford. The building formerly housed a WWII USO and later the Salvation Army. The store-front read: Whole Earth Truck Store & Catalog, a division of the Portola Institute: it was Brand’s clever idea to add the location’s latitude and longitude.

Brand’s office was draped in an orange parachute and in the email to me, he remembered: “Much of the furniture was nailed together by the staff. In the retail front, books for sale had holes drilled through them and were hung on the wall on headless nails. Some products mentioned in the Catalog were sold as well. Since nobody had experience in running a retail store, it became on-the-job training.”

Goodell recalled seeing scribbled on customer receipts: “Thanks for the bread, man.”

The store also became the production center for the Catalog–with type set by hand–but it was printed at nearby Nowell’s Publications.

Distributing the Catalog proved difficult as its large size presented a problem for bookstore owners who didn’t know where to display them. Subscriptions were slow in coming and a grand opening at the store to which the press was invited flopped.

Morale was flagging and then the Whole Earth Catalog caught the fancy of “big media”: Time, Vogue, Esquire.

[In todays parlance, the Whole Earth Catalog was “cool.”]

Flattering coverage brought fresh subscriptions, but the biggest response came from one tiny mention in “Uncle Ben Sez,” a column appearing in the Detroit Free Press, according to a 1972 Pacific Business article authored by Stewart Brand. A reader asked: How do we start a farm? and Uncle Ben printed the address of the Whole Earth Catalog in Menlo Park. Hundreds of subscriptions poured in.

The Catalog became a national success story.

Brand said, then as now, the Mid-Peninsula was an easy place to start things. But it didn’t make him rich, as the media often reported. Brand said he received a non-profit salary.

By mid-1972, an exhausted Brand announced that there would be an exclusive party to celebrate the DEMISE of the Whole Earth Catalog in San Francisco.

After the DEMISE party, Brand said, when overhead went to zero, royalties rolled in for months. The Point Foundation was created to give away more than $1 million in three years, with the recipients as diverse as environmental groups and COYOTE, Margo St. James’ union for prostitutes.

When Random House representatives came to Menlo Park, perhaps to negotiate acquisition of the Catalog, they presented a contrast to the more casually attired crew at 558 Santa Cruz Avenue.

The men from the giant publishing house, wearing nice suits, ties, and wing tip shoes, walked into a room where a young woman employee nursed her infant on an old couch, with the springs popping through the worn fabric.

During the talks, Goodell recalled, people floated in and out, dressed in hippie clothes, but production of the Catalog never ceased, and there was a clattering in the background. The men from Random House fingered their collars but never loosened their ties in the intimate environment.

“Five years earlier, I definitely would have identified with the corporate types,” Goodell said, “but now as part of the Catalog, the strange comings and goings seemed quite normal.”

In 1999, when this story was written, the storefront that once house the Whole Earth Catalog was home to Wessex Used Books & Records, specializing in fiction, history and scholarly works.

Owner Tom Hayden said that he used to get letters from all over the world asking for the latest Catalog. All that’s left of Whole Earth was faint evidence of their photographic darkroom.

Brand moved on. He joined Governor Jerry Brown’s administration, lived for a time in a funky houseboat; more recently (1999), he founded the web site called the WELL and co-founded Global Business Network.

Some people have characterized the Whole Earth Catalog as ahead of its time. In 1999, when Stewart Brand was in his 60s, he said: “I don’t think ahead of its time ever means much. The Catalog was new in several ways. It was a conspicuous success. Success often becomes commonplace soon.”

1970s: The Worm Farm, Skyline, Portola Institute & Where Is My 8 Foot Square Hollow Mahogany Pyramid?

Does anyone know what happened to Richard’s 8-Foot Square Hollow Mahogany Pyramid? Last seen at the famous “Worm Farm” in San Greogrio.

From far-off Chicago, Richard Ledford says:

Hi June,

You have assembled one of the more special websites that I have ever had the pleasure of stumbling upon by accident –halfmoonbaymemories.com

Thanks for putting such meticulous devotion into making something both beautiful and freely shared!

I e-mail you now to ask whether you know, or know of anyone who does know, anything about an 8-foot square hollow plywood pyramid appearing at the Worm Farm in San Gregorio around spring of 1975?

This exact proportional replica of the Great Pyramid was carefully built by me and left with the people living at the worm farm at that time. I am interested in learning what use this pyramid served, and what was its fate over the intervening years. If you, or someone to whom you can forward this message, could send me any information available on this subject, I would greatly appreciate the effort.

-All the best, thanks.

———–

HI Richard:

I was happy to read such an upbeat email message first thing in the morning., I have a number of posts about the great magician Channing Pollock, owner of the unforgettable Worm Farm.

Did you draw the plans for the pyramid water tank? Because I have some architectural plans for it. Here is the link, click here

POST (peninsula open space trust) bought the Worm Ranch from the heirs of Channing and Corri Pollock, who originally purchased the land from Stanford.

Here is the link to POST, click here

George Cattermole and his wife own the Store in San Gregorio and they are certainly up-to-date on what is going on in their “front yard.” The water tank pyramid, if that is what you are referring to, stood just up the road from their store.

Here’s the link to the San Gregorio Store, click here

Was this helpful?

————–

Hi June,

Good to hear from you so soon.

I have just one PIC of the pyramid from my days at the last avacado ranch in Yorba Linda, where I crafted it. As soon as I can scan it, I will send it to you.

The name Channing Pollock rings a bell. It was likely by his magic I was drawn to leaving my pyramid at the worm farm – for no particular or clear reason of having any prior relationship with anyone there -as if he pulled me straight there through the aether, straight to San Gregorio bearing my gift of a precision wooden pyramid.

I did not draw the plans for the water tank pyramid, but I did hear something of this project somehow. Perhaps at the Saturday morning Alan Chadwick organic gardening sessions held at UCSC back then. This may be why I considered the worm farm a good place to leave my pyramid as I left for Chicago. I had previously been living on Skyline Blvd. as the caretaker of the property know as Rancho Diablo, while it was still run by the Portola Institute (Whole Earth Catalog) to hold 20-25 people, 2&3-day educational seminars in the big mansion.

Richard Ledford (Armadillo)

In the 1970s a Giant Redwood Log Landed on the Shores of Miramar Beach

(Image: The Michael Powers homestead in Miramar Beach, with the huge redwood log in front. Photo by Michael Powers.)

In the late 1970s, Princeton shipbuilder Manuel Senteio, arrived at Miramar Beach, driving his crane to move a 20-foot-long, 3000 pound redwood log to photographer/sculptor Michael Power’s healing center, then in development.

The log had washed up on the nearby beach, and when Senteio saw how huge it was, and what his crane would have to lift, he exclaimed: “It’s big!”

Yes, it was VERY BIG AND VERY HEAVY–heavier still, from the sea water that had soaked into its pores.

Could Senteio’s crane lift the thing? To fulfill Powers’ plan, which was to carve the log, it had to stand upright. Could this be accomplished? Nobody knew for certain.

If all else failed, a crowd of Powers’ artist friends were on hand to help “psychically” raise the mammoth totem pole; its destination the peaceful inner garden. Half Moon Bay City Manager Fred Mortensen, a neighbor of Michael Powers, was there to lend more practical expertise.

There were many oohs and ahhs and oh no’s. This was the most dramatic event to occur in Miramar Beach for many moons.

But the crane lifter, Manuel Senteio was a professional: Can you hear the great burst of applause and laughter when the redwood log found its final resting place?

“Within this tremendous mass of redwood brought here to Miramar Beach by the sea,” said Michael Powers, “I intend to carve the forms of a man, a woman, and a child, a trilogy. It will probably take a year to complete but hopefully it will become a source of beauty and inspiration for everyone who comes to see it.”197

Good Rumor: Who were the beautiful people at the Oceano Hotel?

Friends have told me that they spotted some very rich, beautiful looking “hippies” staying at the Oceano Hotel in Princeton-by-the-Sea.

I got excited and asked: What does a rich hippie look like? What were they wearing? What did their hair look like? How many of them were there? What are they doing in Princeton? Making a movie?

The friends smiled broadly as I bombarded them with questions, ending with a harsh reprimand: “Didn’t you talk to them? I would have been ‘right there,'” meaning, I couldn’t pass them by without getting the answer to the most important question: “WHO ARE YOU?”

But my friends are not in the business of asking rich hippies who they are, and what they might be doing in Princeton; instead my friends just looked and admired and loved looking and admiring these seemingly out-of-place people wearing perfectly made counter-culture clothes and beads from the 1960s.

Now I hear that they were from a production company, involved with making a tv commercial for the “Hummer.” Hummers in Princeton?

County Jail, 1870s, Judge Pitcher’s HMB “Courtroom” and Plans (1931) for a Prison South of Town

This is a wonderful drawing of the county jail in Redwood City, circa 1872. Has some institutional feel to it but it also looks like a country home; what do you think?

From “The Illustrated History of San Mateo County,” Moore & DePue, publishers (1878). This beautiful book was “saved” and published by Gilbert Richards Publications, Woodside, California in 1974.

In Half Moon Bay, if you were caught speeding you’d land in Judge Pitcher’s “courtroom.”

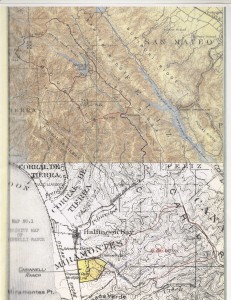

Look on the map below and find the land, Casinnelli Ranch; it’s colored yellow and there’s an arrow pointing to it, below the “Miramontes tract.” In an earlier WWII post, I mentioned Mr. E.J. Casinnelli as he owned 423 acres around the Johnston House.

In 1931, the Cassinelli Ranch, south of Half Moon Bay, was being considered as a location for San Francisco’s City and County Jail in San Mateo County. There are several documents associated with the project that did not materialize. Some people will find the information contained within the reports enlightening so I will provide it here.

Report on Water Supply Possibilities of Cassinelli Ranch as a site for San Francisco City and County Jail

By Charles H. Lee, Consulting Hydraulic Engineer

Description of Property

The Cassnelli Ranch, comprising 423 acres, is located in San Mateo County, California, one mile south of Half Moon Bay. The west boundary fronts on the Half Moon Bay-Purissima Highway for a distance of over 1/2 mile. A surfaced road from the main highway runs along or adjacent to the north boundary for 3/4 miles.

The western portion of the property, embracing approximately 200 acres, is flat land lying along the main highway. It merges into gently sloping land and then broad rolling hill slopes to a crest at the rear of the property. The topography is smooth and practically all of it is clear of brush, giving excellent visibility.

All but a small tract in the northeast corner has been under cultivation for many years. A portion of the flat land has been planted in artichokes and miscellaneous vegetables, and the remainder and the adjacent hill land in hay and grain. The artichokes are irrigated every season and vegetables when water is available.

Leon Creek flows through the Ranch near the northeast boundary for a distance of 3095 feet, where it has a cut channel approximately 35 feet deep and 100- to 200 feet wide. This stream is a tributary of Pilarcitos Creek, joining it at Half Moon Bay about 1-1/4 miles below the Ranch and flowing thence to the Pacific Ocean, a distance of 1-1/4 miles.

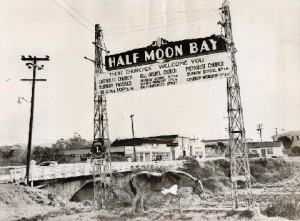

Welcome to Main Street in old Half Moon Bay

Thank you, Tony Pera, for the photo. Tony, almost single-handedly returned the Ocean View Lodge in the IOOF building on Main Street, back to its former glory. You can’t imagine how many hours and days of his private time he gave up to complete this major project. He’s so special, a rarity, the kind of community-minded fellow who was more prevalent in earlier times, when people got together to help a family in need, or to rebuild a house that had burned–Tony’s a man who really cares about his community, and all I can do to show my appreciation is to honor you in this blog space.

Want to know more about the Ocean View Lodge and the IOOF Building? Click here

Coastside WWII: “In the first part of 1942, ‘G-Men’ came to our home in Moss Beach.”

Elaine Martini Teixeira says:

Sometime in the first part of 1942, before my brother left for service in the US Army in October, government men came to our home in Moss Beach.

My brother, Raymond Martini, recalls they showed some official papers, but said they were not given to the family to read, and we do not know if they were FBI or what was then called G-Men. My Dad was not a citizen; he was born in Brazil, though of Italian heritage. He came to America from Italy; the family returned to Italy after a few years in Brazil, where they had gone to find work. My dad and one brother were born in San Paolo, Brazil.

I do not know what these men said exactly, but the family was told that my Dad had spoken well of Mussolini. When my Dad came to America at 16, sometime in 1913, he probably did have a good opinion of him. it was much later that Mussolini became more of a controversial, political figure.

When my husband & I toured Italy in the mid-eighties, people said Mussolini had done well for the country when he first came to power; he did similar things as our president had done; he built up the roadways, trains, etc., had tunnels constructed through the mountains and opened up Italy to travel and transportation to France and Switzerland. Additionally, this gave work to the men who were unemployed.

My Dad never returned to Italy after he came to America. I can say, he never spoke to us about the Italian government, or said anything particularly favorable about it. He neither wrote or read in either Italian or English; he probably did not know a lot about the situation in Europe. My father was certainly not a political type of person. He was just a hardworking man raising his family.

I remember being in my bedroom and my Mom came and said we needed to get into the living room as these men had arrived. There were at least 2 or 3 of them, and they wanted us all in one room. They proceeded to search the house. We did not see a search warrant, or anything else, to indicate they had official status to be there there. Maybe, during the war, it was not necessary, and I am sure my parents did not ask about it. We were all rather afraid of what was going to occur.

Additionally, they might have been looking for a shortwave radio. Mainly, they found some rifles that belonged to by brother, as he was an avid hunter. One rifle might have been my Dad’s; he was a farmer, and they were allowed to shoot rabbits that ate the crops. My brother took responsibility for the rifles so they would not cause any additional problems for my father.

Mostly, my older sister, myself and my younger sister were sitting in the living room, and what transpired was related to me, later, by my Mother. She felt that someone who may have been upset with my father over something, probably had reported him to the authorities.

Finally, after quite some time, my brother, who was visibly upset, reminded the ‘G-Men’ that he had enlisted in the service and would be leaving for the army air force. He asked: Did they feel my dad would send messages to the enemy so they could sink a ship that would be taking his own son to Europe to fight?

The government men had no answer for my brother’s question. They left and we never heard from them again.

——————

To view a youtube video that tells more about the LA STORIA SEGRETA (secret story in Italian)

please click here

There was also a successful exhibit called “La Storia Segreta” that traveled the United States and was well received at the courthouse in Redwood City.

Coastside WWII: On the Wrong Side of Main Street

By June Morrall

I wrote this shocking story in 2003.

During WWII, Half Moon Bay’s Main Street, and everything to the west, including the beaches, was off-limits to those folks without citizenship papers

It was a frightening time on the Coastside. If you were Italian in Half Moon Bay at the beginning of World War II–and didn’t have citizenship papers–there was a possibility of danger and humiliation.

At the time was broke out, Half Moon Bay was a close-knit farming community and Main Street was the hub of the small town’s commerce. The locals shopped at the same stores, ate the familiar restaurants, raised their glasses at the saloon, prayed at the beautiful Catholic Church and sent their kids to the grammar and high schools.

But all that changed after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

“I was in church that Sunday,” Josephine Giurlani Silva Revheim recalls, “and the next day the U.S. Army and Navy signal corps trucks were driving into Half Moon Bay. They took over the hotel and other buildings all the way up the coast towards Devil’s Slide.”

Today (2003) “Jo” Revheim is a retired nurse, a widow and longtime Pacifica resident. At the start of the war, she was the 15-year-old daughter and only child of farmer Antonio Giurlani and his wife Marianna.

The Giurlanis grew sprouts and chokes on land adjacent to the old Catholic church that once stood west of Main Street. In between masses, Jo helped tidy the church, and she recalls ironing shirts for the much-loved Father.

The Giurlanis had come from Lucca, Italy, but Jo’s mother was actually born in Marseilles, France. Still, everyone in Half Moon Bay considered her Italian.

Soon after the army trucks rolled into Half Moon Bay, Josephine remembers, her father received an offical letter from the U.S. government ordering the family to move to the east side of Main Street.

They were also required to register in San Mateo.

Why did the officials select Main Street as the place to draw the line, separating east from west? Main Street was the Highway 1 of its time, and everything to the east, including the beaches, was off-limits to those folks without citizenship papers.

Josephine recalls that the grocery store, the bakery and everything else was on the west side. The east side was where people lived, and unless you had a relative to help, there was no place to move to.

Printed notices ordering all “aliens, German, Italian and Japanese” to re-locate were plastered on telephone poles in the town. The Japanese were rounded up and detained at Tanforan racetrack in San Bruno. Their history is well documented. But in Half Moon Bay, Josephine notes, there was no central location for the Germans and Italians. After registering in San Mateo, they simply had to leave their homes on the west side.

The while line painted down the center of Main Street not only separated east from west, it made some lcoals suspicious and fearful of those who did not have citizenship papers and had been pushed away. A person who had been your friend a week earlier might turn sullen and threatening.

“We were never to cross that white line!” Josephine exclaimed today (2003).

Crossing meant that they would surely be reported and possibly dragged before the local judge, or worse. Fortunately, not everybody was mean.

For example, Judge Manuel Bettencourt, was kind and showed compassion when dealing with non-citizens.

But there were exemptions to the order, and Jo says since she was younger than 16, she was not required to move. Neither was her mother, being French. The order was clearly aimed at Jo’s father, an Italian with no papers and little education.

Technically, Josephine and her mother could have stayed on the farm but she asks: “How could we maintain a large farm without dad’s help?”

The decision was not difficult. Whatever the hardships, this family would stick it out together.

How many families faced similar circumstances? Jo estimates some five to ten Half Moon Bay families were in the same boat.

In instances, where some family members had papers, and some didn’t, they had to decided whether to break-up or cross the white line together.

There’s the story of one family that operated a business on Main Street. The parents, without papers, had to shout instructions to their citizen children across the street.

How could this happen? How could a white line tear apart the social fabric of a small farming community?

The attack on Pearl Harbor had created an atmosphere of near panic. It’s no surprise that people on both sides of the white line were faced with impossible decisions.

Would the Japanese invade California?

Military experts had long recognized the logistical importance of the Coastside. In the late 19th century they warned that Half Moon Bay could prove to be a “back door” for a foreign, hostile fleet. The enemy could land at Pillar Point and march, without resistance, conquering all of San Mateo and San Francisco.

After Pearl Harbor, desperate measures were taken to protect the Coastside, to close that vulnerable door. The military patrolled the beaches, bunkers were built–some of those WWII relics can be seen today from Highway 1 near Devils Slide–and gun emplacements dotted the hills overlooking the Pacific.

Local citizens volunteered to scour the beaches looking for submarines and scn the skies for enemy aircraft.

Meanwhile, Josephine’s family dealt with their own emergency, scrambling to find a roof to put over their heads. The government had given all the aliens a two-week deadline to relocate. The Giurlanis had to harvest their crops and move everything they had, including the goats, chickens, rabbits and horses. Incidentally, they were prohibited from taking radios and guns.

As the two-week deadline crept closer, it was like a noose tightening around theirs.

Then a fortuitous turn of events.

“Luckily,” Josephine says, “Dad had a farm friend, Mr. Cassinelli, who owned a large ranch in Higgins Canyon, south of town. He not only hired dad, he gave our family a place to live in the Johnston House. In those days it wasn’t called the Johnston House–we called it ‘the old house on the hill’.”

The old house was vacant, and the local kids were convinced it was haunted.

“Finally, at midnight, the deadline time for the great move,” Josephine says, “we loaded up all our belongings and animals and made our way through town and landed in the Johnston House.

“the next morning,” she continues, “it hit us, what we were in for. The rat-infested house had no windows, and vagrants had slept there, leaving behind garbage. Straw covered the dirt floors, the outhouse was halfway up the hill in the back, and when it rained, it was like a waterfall, but there was plenty of room, and thank God there was cold running water to drink.”

Most important, the house was located on the “East” side.

But the worst part for Josephine, the teenager, was not knowing: “When could we go back to our home, if ever?”

Sitting in her charming two-story home in Pacifica today (2003), Josephine Revheim reflects on those tumultuous days. “We had no way to purchase food for our families, unless we disobeyed the law and crossed the street to buy it, and guess where all the stores were?”

They were on the wrong side of the street for the Giurlanis.

The school was also on the west side, and she couldn’t go there.

The most humiliating part of the whole experience for this teenager were the stares and unfriendliness she and her family encountered.

There were times when the Giurlanis were able to circumvent the restrictions. On one occasion Josephine and her mother harvested the artichokes at their farm on the west side while her father, prohibited from going himself, waited in the car on the east side. They got the chokes back to the Cassinelli ranch where they were crated and sent to market in San Francisco.

Some of her remembrances are so unpleasant that Josephine is uncomfortable even thinking about them today. She quirms when recalling that one malicious neighbor actually reported her mother’s visits to the farm on the west side.

Even though she was French she had to appear before Judge Bettencourt to prove she wasn’t subject to restrictions, and the good judge reassured her of her exempt status.

The worst recollection of all was of her mother successfully fighting off an assault by some angry, unthinking local.

“For the Italian families, the nightmare ended after about five months. Josephine reminds us that “the Japanese had it so much harder and suffered so much and lost everything.”

As to those German non-citizens on the Coastside, Jo had no information.

“We came home,” she says, “and at least the house and barn were still there. Everything else was gone, the crops were gone, and even our wild pigeons that had nested in the barn were gone.”

The Giurlanis were back in the house and it wasn’t long before they received a letter from the U.S. government advising them to become citizens or face deportation. They all got their citizenship papers.

For a time, the family continued to farm the land beside the old Catholic Church. Later, they moved to Pacifica, where Jo’s father worked in construction for the developers Doelger and Oddstad.

Josephine married, became the mother of three children and attended the College of San Mateo, earning her degree as a licensed vocational nurse in 1963. She spent 15 productive years working on the eighth floor at Peninsula Hospital in Burlingame.

(Jo Giurlani Silva Revheim (center) with fellow College of San Mateo nursing graduates in 1963.)

(Jo Giurlani Silva Revheim (center) with fellow College of San Mateo nursing graduates in 1963.)

When Jo’s parents fell ill, she tended them with great love until the end of their lives.

Jo Revheim still has friends in Half Moon Bay and visits regularly.

One source of constant amazement to Jo is how magnificent the Johnson House appears today, compared to the hovel she lived in with her parents more than half a century ago. She takes particular pride in the help she provided to the Johnson House Foundation when they asked her for sketches of how the house looked in the 1940s.

——————

——————

Shortly after my interview with Josephine Revheim, we took a ride to Half Moon Bay to see the house she had lived in as a 15-year-old before her family was ordered to move out of it. Surprisingly the house was still standing, but it was vacant and uncared for, with broken glass on the floor, grafiti on the walls, empty paper coffee cups, somebody’s crash-pad, and, right there, in the middle of town.

Here are some photos from that day; arriving at the house, looking at the washing machine inside. Josephine is the lady in pink.