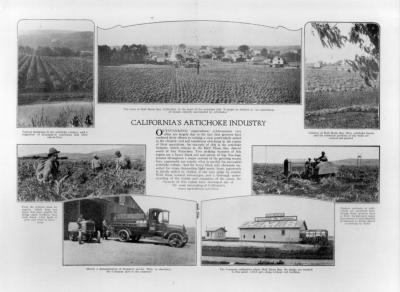

Way, way, way in the background stands the beautiful North El Granada Train Station–still standing near the gateway to Princeton. Click, click, click to enlarge the images!

Way, way, way in the background stands the beautiful North El Granada Train Station–still standing near the gateway to Princeton. Click, click, click to enlarge the images!

Anniversary of the Shipwreck of the New York at Half Moon Bay (the longer version): Part III

Devastating storm damage to the hard luck ship New York left her without a fore topgallant mast, topsail yard and the skysail yards on the foremast were blown awayâplus the mainmast was left without sail.

The increasingly nervous crew, whose first mate lay in his bunk seriously ill, felt certain they would never see San Francisco, and to each other they confided their fears that their lives would end right there on the high seas.

âIt took many hours hard work to get things straightened out,â? crew member Paul Scharrenberg wrote in 1901, âand as there were no extra spars aboard, we had to let her go under the new rig with a skysail on the mizzen and lower topsail on the foremast. Her steering had been bad enough before, but from that night the good ship could not be made to readily respond to her helm.â?

Gales beat up the New York until she reached Southern California, where the winds quieted down.

âIt continued this way until Sunday morning, the 13th of March,â? Claire, the ship captainâs daughter recalled, âwhen we found ourselves in the vicinity of Half Moon Bayâ¦Then a northerly wind came up, and the seas became turbulent again, swinging wildly about a ship that would not answer her helmâ¦â?

They were only one day away from San Francisco harbor, Captain Thomas Peabody assured his frightened daughter. Comforted, Claire slept an hour in her bunk until loud voices and strange noises woke her up.

The New York shivered and shook, glassware hanging in racks on the cabin wall crashed to the floor, wildly swinging lanterns flickered out.

Claire was consumed with fear as she bolted out of bed, calling for her mother. Together they scrambled up the companion way, opened the door and stood frozen in terror.

âJust then,â? Claire tells us, âa gigantic wave rolled over the ship, and she lurched wildlyâ¦â?

âGet below, both of you!â? shouted Captain Peabody. âStay there until I come down to you.â?

Two hours later Captain Peabody slipped below deck and told his wife and daughter they were aground on the sands of Half Moon Bay. When the full moon rose, he said, he planned to order the lifeboats lowered, rowing everyone to safety through the churning surf.

All day the people of Half Moon Bay had watched the twitchy movements of the ship from the beaches. Some carried whiskey, waiting on the sands near the foot of Kelly Avenue for the outcome.

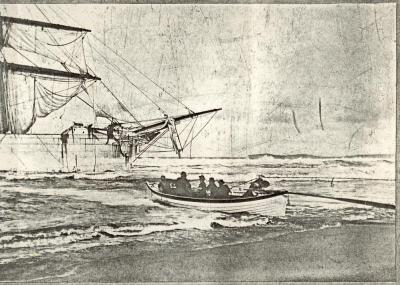

At 1 a.m., First Mate Callip, still suffering from a bad âcoldâ?, and in charge of seven seamen, swung a lifeboat from the davits. Captain Peabody placed his daughter and wife in the stern of the small craft and the men were ordered to pull away from the ship. But as they neared shore, the strong undercurrents capsized the boat, tossing its occupants into the frigid waters.

When the Coastsiders saw the boat capsize, they formed a human chain, wading out into the turbulent waves, reaching for Claire and her mother, bringing them safely ashore.

As mother and daughter huddled around a blazing bonfire eating steak provided by the kindly townspeople, First Mate Callipâs impulse was to rescue those still aboard the New York. But he couldnât get help from the sailors who now were too drunk from drinking whiskey to rescue their shipmates.

Finally, a second boat was launched from the New York, bringing ten more seamen ashore. But during the launch the cook, Ah Lee, caught his leg in the craft, fracturing his knee.

As was maritime custom, Captain Peabody was the last to leave the ship.

â¦To Be Continuedâ¦

Whangpoo River, Another Time

Anniversary of the Shipwreck of the New York at Half Moon Bay: (the longer version) Part II

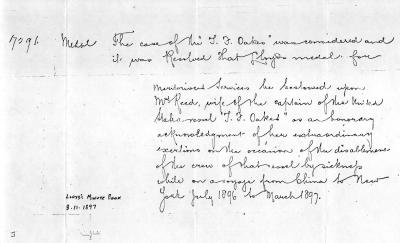

The T.F. Oake’s 1896-97 voyage from Hong Kong to New York harbor had been hard.

Unfavorable winds challenged the crew, and with food rationing, illness broke out among the men, leading to the death of the Chinese cook on November 11. In quick succession, five more sailors were buried at sea. The remaining crew, not including the first mate, Captain Reed and his wife, Mary, fell desperately ill with scurvy, too weak to move from their bunks.

The singular bright spot during the bleak voyage was Mary Reed’s bravery. Described as “a woman of masculine proportions”, her husband proudly called her “the best man aboard ship”. During a terrific March 1, 1897 gale, and when the Oakes was off Cape Hatteras, it was Mary Reed who singlehandedly took over the ship’s wheel, attending to the halyards and the sheets.

(Mary Reed’s heroism did not go unnoticed–Lloyd’s of London, the vessel’s insurer, awarded her a special commendation).

A few days after the Oakes limped into New York harbor, her surviving sailors filed charges against Captain Reed in U.S. District Court, claiming he willfully withheld food. At the trial, the sailors testified to his cruelty and their near starvation. The jury found Reed not guilty. Citing precedent for their decision, the jury noted it was an unusual voyage, and not unexpected that men fell ill. In a related civil lawsuit, the crew pressed charges against Reed for neglect and that he had not supplied sufficient food–a New York judge awarded the plaintiffs $2,914.

During litigation, the T.F. Oakes was sold to Lewis Luckenbach. Concerned about sailor’s reluctance to work on a ship with a shady past, her name was changed to the New York and the popular Thomas Peabody hired to captain her.

The New York’s maiden voyage form New York to Asia and San Francisco commenced on May 18, 1897. On board the ship loaded with oil were Captain Peabody’s wife, Clara, and their seven-year-old daughter Claire. Peabody brought along hs optimism: “New captain, new name, we shall be lucky,” he said.

Crew members included the tall, thin, quiet first mate, Callip, and San Mateo County resident Paul Scharrenberg, an “industrious, brown-haired, blue-eyed lad”–later director of the California State Department of Industrial Relations.

The New York plowed through the Java and China Seas and after nine months in deep water, sailed up the Whangpoo River, dropping anchor at Shanghai, where they sampled the teeming city by rickshaw, before returning to Hong Kong.

During the month-long stay in Hong Kong, bird shops fascinated young Claire, where caged monkeys jumped up and down to attract attention. On a shopping spree, Claire’s mother bought a pure white, screeching parrot with a pale green topknot. The parrot was now a part of the New York’s crew.

Preparing to sail for San Francisco, coolies loaded porcelain, silks, rice, wine, tea, peanuts, teakwood chairs and firecrackers aboard the ship. “Bright with Chinese characters”, the cargo boxes smelled of incense and spices.

On January 14, 1898, the New York sailed out of Hong Kong harbor, but “from the first day we left China unil we sighted the California coast we had a miserable time,” wrote Claire Peabody in her book, “Singing Sails” (1950).

Non-stop storms pushed and pulled the vessel. Protected by waterproofed oilskins, Captain Peabody gave orders to the crew, a crew that whispered that the New York was a doomed ship. They feared they would never see San Francisco.

Worse, the First Mate, Callip, fell ill with a “cold” that didnt’ improve; the Captain stood his watch.

Surrounded and battered by rough weather around Cape Horn, little Claire Peabody continued her on-board education, memorizing Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poems.

When the ship was 850 miles west of San Francisco, the crew encountered a gale so terrible that it “snared the iron ship in its teeth”. The New York rolled around helplessly in tremendous seas, often in danger of foundering.

(Document below: Lloyds of London awarded Mary Reed a medal for her courage. Click to enlarge)

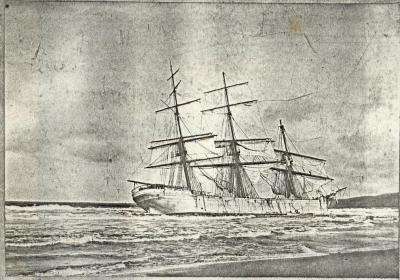

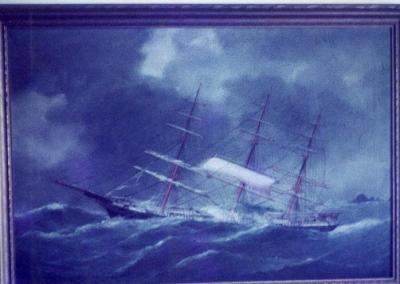

Top: Painting of the T.F. Oakes by Mary Reed, who was also known as Hannah.

…To be continued…

Anniversary of the Shipwreck of the New York at Half Moon Bay (the long version) Part I

Anniversary of the Shipwreck of the New York at Half Moon Bay (the longer version) Part I

Sailors all over the world were familiar with the iron ship New Yorkâs shady pastâbut her builder intended a much grander future for the experimental vessel.

As the second iron ship built in the U.S. in 1883, she was launched with great promise on the Delaware River. Originally called the T.F. Oakes, her champagne christening was good enough for a celebrity going on a voyage, the sea of waving white lace handkerchiefs, cheers and more cheers and the shrill steam whistles.

The Oakes wasnât the only celebrity. Her 42-year-old builder, the naval hero Henry Honeychurch Gorringe, was already famousâhaving masterminded in 1880 the transfer by steamer of âCleopatraâs Needleâ?, a 200-ton obelisk from Alexandria, Egypt to New Yorkâs Central Park.

Heading up the American Shipbuilding Company, Gorringe planned to build ships of the future, not of wood, but ironâmodern vessels competitive with the profitable foreign shipbuilders.

But the Oakes was a flawed vessel. Engineering errors and a reduction in speed caused by the âfoulingâ? of her iron bottom caused the Oakes to become known as a âsailing trampâ?, unable to match the competition. Gorringeâs company produced more iron ships but incompetence and an excess payroll drained remaining resources, pushing him into bankruptcy. Less than two years after the launching of the Oakes, Henry H. Gorringe died from injuries suffered in a freakish fall from a train.

By 1893 experts found it easy to predict that the Oakes would set a new record for the slowest passage from New York to San Francisco. The fastest run over the route took 111 days; the Oakes took an embarrassing 195 days.

Three years later the ship was many months late on a voyage from Hong Kong to New York. More than 259 days after beginning her voyage, the âmystery shipâ? hobbled into New York harbor, towed by the British oil tanker Kasbek. Several skippers whooped for joy, tossing their caps into the air, but other spectators were saddened at the sight.

Only 18 of the original 24-member crew survived the long voyage; scurvy, a Vitamin C deficiency, left them unable to walk without help. A strict federal law required all vessels to carry a variety of food, water and lemon juice, but the Oakes, out in the turbulent seas for more than a year, had long since run out of provisions.

Combative weather, including the terrific force of a four-day typhoon, thrust the ship, captained by Edward Reed, far off its course. Partially disabled by a paralytic stroke, Captain Reed depended upon his wife, Mary, to give commands to the crew. Since he realized the Oakes was slow anyway, Reed chose to sail by way of Cape Horn to New York, thousands of miles further than the regular route via the Cape of Good Hope..

â¦To be continuedâ¦.

Is this the “wedding cake” mansion?

108th Anniversary: Shipwreck of the New York

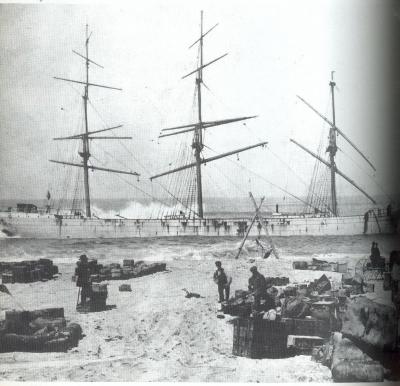

On Sunday, March 13, 1898, the iron ship T.F. Oakes–a vessel so tainted with bad luck that it was renamed the “New York” to ward off evil spiritsâfulfilled its destiny, losing its way– surrendering to the pull of the waves rushing it toward the beach at Half Moon Bay, the ship’s final resting place.

During the “New Yorkâs” last hours at sea, the local townspeople gathered on the beach, some of them carrying whiskey, watching the silhouette of the ship struggle to live, to get back on course– ultimately a hopeless challenge.

Knowing the outcome, the people of Half Moon Bay built a huge bonfire, and brought food and warm clothes for the survivors who came ashore with the help of the locals forming a “human chain” from shore- to- ship. (The Chinese cook injured his leg and the first mate, already ill with a cold, later died at a San Francisco hospital).

On its maiden voyage as the “New York” the ship was sailing from Shanghai and Hong Kong to San Francisco, its cargo an exotic mix of carved dark furniture and cloisonnéâtea and firecrackers.

On board was kindly Captain Thomas Peabody, his sweet wife, Claire, and precocious daughter, Clara, who, in 1950, penned âSinging Sailsâ?, the memory of her adventures aboard the doomed vessel–a book you can find in the archives of the San Mateo County History Museum at Redwood City. Just as the name of the ship had been changed from the T.F. Oakes to the New York, the new owners sought to cover all the angles by carefully choosing a benevolent captain. The Peabodys projected the image of a fairy tale family, surely able to thwart any lingering evil spirits.

Souvenirs from the shipwreck of the New York were proudly displayed in Half Moon Bay homes, a memory of one of the Coastside’s most exciing events.

Kid Zug in Pescadero: Part IV

In 1919 a battered and bruised Frank Goularte, the 40-year-old son of the Pescadero blacksmith, was anxious to talk to the authorities about the beating he had received from Kid Zug– the recent winner of the highly anticipated outdoor bout with “Happy” Frey, son of the village bartender and constable.

“I was on my way to a dance,” Goularte began. “Before going there I stopped at San Gregorio to get a shave and when I left the shop,” the blacksmith’s son said he was suddenly, violently assaulted by Kid Zug. He intended to bring charges against the pugilist.

When he appeared before the Justice of the Peace in Redwood City, a wounded and angry Frank Goularte charged Zug with battery. A trial date was set and the Kid appeared before a jury in November 1919.

The evidence presented at trial definitely proved that the attack had occurred–but the jury believed Zug’s version of events, citing that his actions were defensible and justifiable. They were convinced that Goularte had directed slurs at Zug and made a move that looked as if he were about to draw for a gun. Kid Zug was acquitted of all the charges.

Insiders guessed at the truth: Frank Goularte was an important witness in the murder investigation involving the death of Sarah Coburn, a wealthy Pescadero widow. He lived across the street from Sarah, and on the night of her murder, had observed the comings and goings of possible suspects. His testimony could prove to be devastating to Zug’s employer–believed to have played a pivotal role in the slaying.

Some folks in the know believed the beating Kid Zug administered to the blacksmith’s son was a clear message to Goularte to keep his mouth shut.

Perhaps Zug’s influential employer was responsible for suppressing the murder invesstigation and having the whole matter dumped into a permanent cold case file.

By 1920 few people were even talking about the murder case.

Kid Zug quietly packed up his few belongings and left the Swanton House and Pescadero forever.

The END

“Peculiar” Rocky Rocks…

Remembering Bill Doerner

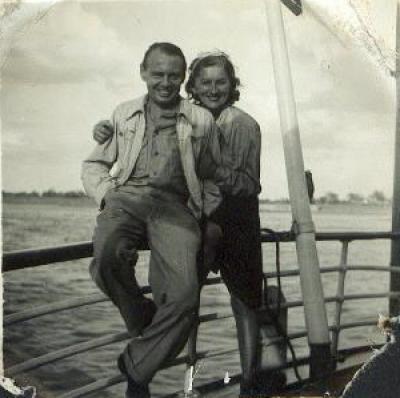

At left: Me, Bill Doerner and Reporter Dick Thompson.

At left: Me, Bill Doerner and Reporter Dick Thompson.

<a href='http://halfmoonbaymemories.com/wp-content/

Bill Doerner was a writer for Time magazine in New York before he was sent out West to take over as head of the San Francisco news bureauâjust as AIDS began to decimate the gay community and when angioplasty was becoming a popular option for clogged arteries and the two Steves, Jobs and Wozniak, had built the clunky looking Apple II.

I worked for Bill. I was the news bureauâs office manager,a temporary position, until the âregularâ? office manager returned from maternity leave.

Bill wasnât the warmest of people or the most fun. He could make you feel very uncomfortable because I think he felt uncomfortable. He seemed a tad snottyâbut beneath all that I discovered a deeply kind man.

When he made the move to the Cityâwhich proved to be as temporary as my stint as the office manager– Bill Doerner left behind the excitement of Manhattan, an apartment on West 70th Street and a weekend place in East Hampton.

Heâd been born in Missouri in 1941 and spent his entire life in the news business, beginning his career in St. Louis.

Being a writer and a bureau chief require a different set of skills– like morphing from an introvert to an extrovert. To me, the former describes Billâs personality. More inside than outside. (Some of Timeâs bureau chiefs are the stuff of legend and Bill Doerner did not fit into that categoryâIâm thinking in particular of the bureau chief Bill was replacing, a beloved but wild fellow everybody soley missed).

But San Francisco began to work its magic and I could tell Bill was falling in love with his new home. One day he asked me what it means if a guy wears one earringâ¦.and he wanted to know, what does it mean if he wears it on the left versus the right earâ¦.You know, I knew the answer but I just couldnât remember so we had a good laugh, me terribly flustered the whole time, wishing I could give him the definitive cultural explanationâbut he got the idea.

Another time it was Billâs day off when he called me at the office. His voice sounded shaky; he told me he had just been through a terrifying experience. Bill had gone to purchase some items at a discount store when a robber with a gun ordered all of the patrons to lie down on the floor, and he was one of themâthoughts racing through his mind as he heard "and donât move or Iâll shootâ?.

Hard as I tried, I couldn't imagine Bill in that situation.

After I went on a whale watching trip, sailing out of Pillar Point Harbor, here on the Coastside, I wrote a story called, âWatching Whale Partsâ?. Why did I give it that title? Because thatâs all I saw from the boat, parts of whales, never the entire mammal. I asked Bill to read it and he liked the story, calling it âsurrealâ?, and encouraging me to submit it to a publication.

Bill Doerner was a terrific writer, admired in the news bureau as one of the first to write about the AIDS epidemic in the City.

His stay in San Francisco was brief and one day he returned to the Time-Life Building in New York City. I canât say that I kept in regular contact with Bill, but every couple of years, or so, Iâd send a Christmas card with an update. I was both pleased and surprised that he always answered my notes, usually with a one-page typed letterâand he always showed interest in my writing.

In the spring of 1994, a decade after I worked for him, Bill completely rearrange his life. ââ¦I am currently a person of leisure,â? he wrote, âwith more reading on my handsâ¦.The late nights and deadlines, as well as a changing corporate atmosphere since the merger, finally began taking their toll.â?

After 27 years with Time he had taken an early retirement.

And of the future: âIâm planning to pretty much take the summer off in East Hampton, where I have a weekend place, and then decide where to try to go from hereâa part-time job, perhaps, or free-lancing?? I just donât know at this point.â?

The next Christmas he wrote, â Iâm still thoroughly enjoying post-TIME life,â? adding that , âMostly Iâm doing things I never had time to do over the years, like gardening at my weekend place out on Long Island. Iâve also done a bit of free-lance writing. But nothing major.â?

I didnât send another card until after 9/11. When I received his response, the first thing I noticed was a different return address. Not New York, but Missouri. Also this short note wasnât typed but handwritten.

He said that my letter caught up with him "in St. Louis (or a suburb of) where I grew up and to which I have retired to live. I left N.Y. just three days before the WTC tragedyâ¦..â?

A year or so passed, and I remembered that I had taken photographs of Bill at a San Francisco restaurant where the news bureau staff was celebrating his birthday. I now owned a scanner. I could blow up the old prints, I thought, and he might get a kick out of seeing them. Maybe he never even saw them before. I mailed the best of the pictures to Bill's Missouri address but this time there was no response.

It didn't go unnoticed.

In March a letter arrived from Bill Doernerâs sister. She wrote: ââ¦My brother had been in declining health for the past six or seven years. His heart just gave out. I thought you would want to be aware of his death.â? She had no idea who I was but she referred to the photos I had sent, adding that she didnât know if her brother had seen the pictures.

I hope he did.

William (âBillâ?) R. Doerner

Date of Birth: January 31, 1941

Date of Death: March 15, 2003