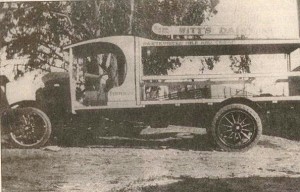

[Image: The Witt Dairy was located in Colma.]

[Image: The Witt Dairy was located in Colma.]

After the death of 97-year-old Evelyn LaFrance Witt in Menlo Park nine years ago, Wendy Witt discovered two dusty suitcases in her grandmother’s closet. They were bursting with old photos, yellowed newspaper clippings, letters and documents, the raw material of her family history.

A UC Berkeley and University of Santa Clara graduate, Wendy Witt is an attractive 44-year-old attorney, who practices family and some criminal law at her San Jose firm: Witt & Reyes.

Wendy meticulously sifted through her treasure, bringing the collection to life.

“I was looking for my grandmother’s recipes,” Wendy says. “She was a good cook and made great ravioli.”

Wendy explained that although her grandmother’s parents were French, she learned the art of Italian cooking from “tons of Italian friends” in Colma where she grew up.

Wendy had a fuzzy portrait of her grandfather, Albert Witt, Colma dairyman and county supervisor. She was 5-years-old when Witt died in 1969. But as she studied the old photos and documents, a clearer image emerged of the grandfather she fondly remembered carrying her around as he watered the garden at his Menlo Park home.

The story of the Witt family began in Colma where dairies and farms once dominated the rural landscape.

In the 1880s, when he was 10, Albert Witt’s father, also called Albert, traveled from Germany to California immediately settling in Colma, where friends of the family already resided.

Albert, Sr. toiled on nearby farms, was frugal, and soon purchased a lucrative milk delivery route. Success followed, and after the 1906 earthquake and fire, he founded the Witt Dairy Company. Producers of milk, butter and ice cream, the Witt Dairy was located between East Market and Chester Streets where Colma Elementary stands today.

Al, Sr. had long been married to Elise Faulkman, and in 1900, blond, blue-eyed Albert, Jr. was born. When he wasn’t at school, the little boy helped with chores on the Colma dairy farm.

At the onset of Prohibition when his father expanded interests to Half Moon Bay, the now 19-year-old Albert, Jr. had familiarized himself with all aspects of the dairy operation.

“My grandfather loved the Colma-Coastside area,” said Wendy Witt. “He knew every inch of it and the name of every ranch owner.” These connections surely helped him later with his political career.

In the 1920s he married 26-year-old Evelyn LaFrance, also a Colma resident.

The most interesting piece of correspondence Wendy uncovered was evidence that may have accounted for her grandfather’s entrance into county politics. She believes the turning point came when the Witt Dairy Company opposed a tax imposed on San Mateo County dairies delivering milk to San Francisco. Letters reveal some details of a legal case concerning milk inspection procedures and taxes on out-of-county milk deliveries.

The Witt family obviously believed getting involved in politics was the best way to protect their dairy interests.

“My great-grandfather put up the money for Al to run for county supervisor,” Wendy recalled.

On the plus side, Al Witt, Jr., a Republican candidate, revealed himself as intelligent and good-looking, with a warm, friendly smile. On the minus side, he might not have been “the most diplomatic person,” admits Wendy Witt. “Maybe he was too direct, but remember he wasn’t a career politician.”

As the population approached 100,000, San Mateo County found itself in transition from a rural area to an industrial center. Al Witt, Jr. best reflected this change. On the one hand, he was a successful dairy farmer, and now as a citizen-politician was getting involved with “brass knuckle” local politics.

Al Witt, Jr. was 32 when he asked voters from the First District, including Colma and Daly City, to elect him in 1932. At that time supervisors were still chosen by voters from their district, a practice soon to change to elections-at-large.

Voters liked Al Witt, Jr., electing him with a great majority. As one of the youngest candidates to ever win a seat, he joined a board comprised of older, seasoned politicians.

Witt chose a tumultuous time to enter politics. The bull stock market of the 1920s had collapsed. The federal government had initiated the Work Projects Administration (WPA), but they needed the cooperation of local politicians to implement the programs and get people to work.

But there was another insidious force in the county. Maybe it was the vestige of Prohibition or the county’s earlier sordid history as the “legal” playground for activities outlawed in San Francisco.

———-

Gambling was of great concern to many. Bookmaking and slot machines were no longer confined to specific areas in the county, and the political machine supporting them was growing more powerful.

Before Al Witt, Jr. took office, a grand jury reviewing criminal activity had issued a scathing report directing officials to shut down gambling houses. When Witt began attending board meetings in Redwood City, a second report was issued, criticizing officials for not doing their job. The gambling houses continued to bustle with activity, and the men behind the political machine attempted to stifle the reformers.

Pointing to the board of supervisors, the jury report cited lack of harmony among members, charging that “existing internal strife and political alignment within the board of supervisors had done much to retard the county’s progress.”

Board meetings were contentious affairs with alliances formed, severed and reformed. Supervisor Rosalie Brown was singled out for not submitting official invoices for work performed by the road master. She paid him with cash from the county treasurer. She explained this was the way things had always been done.

Half Moon Bay Supervisor Manuel Francis was found to have “purchased tires for his former county car without the formality of first obtaining requisitions from the county purchasing agent.”

New Supervisor Al Witt, Jr. wasted little time adapting to the board’s contentious climate, and suffered his share of criticism. The jury report cited the weekly confrontations between Supervisor Witt and the county engineer, a fellow he deemed incompetent and wanted to replace. The jury also accused Witt of “hiring trucks in an amount of $1,100, when authorized to spend only $500, disregarding proper procedure.”

Just as he quickly became entangled with the board’s controversies, Supervisor Witt became identified with positive county programs. He visited Washington, D.C. to get WPA money for local projects, and earned favorable press coverage for Half Moon Bay artichokes by bringing a crate of the thorny vegetables to Mayor LaGuardia in New York.

In December 1935, for example, many WPA activities were completed, including culverts, sewers and roads at Memorial Park, Miramar, Woodside, Jefferson Avenue, San Francisquito Creek, Belmont, 39th Avenue, Brisbane, Salada Beach and many other locations.

Supervisor Witt was most proud of the county’s park and beach acquisition project.

Before he took office, the County purchased 310 acres of redwood forest on Pescadero Creek for what would become Memorial Park. As supervisor, he helped further develop Memorial Park and was gratified when funds were set aside for the purchase of more than three miles of ocean beach lands.

“He loved the Coastside and the beaches,” said Wendy Witt, referring to her beloved grandfather. “He was interested in preserving them with full public access.”

The most outstanding acquisition, wrote Supervisor Witt in the California Beaches Association Monthly Bulletin, was the purchase of some 50 acres south of the San Mateo-San Francisco county line, through which the first leg of the San Francisco to Santa Cruz highway had been completed. This 50-acre park site encompassed the Mussel Rock area.

Witt announced he would run for a second term, aligning himself with Half Moon Bay’s Supervisor Francis, who had long served on the board. But the rules had changed. For the first time, supervisors would be elected-at-large with winners determined by total county votes rather than district-by-district. Although Supervisor Witt

[more coming]