A few months ago I received a fascinating email from San Francisco artist David Gremard Romero. He wanted to know more about the Coastside “outlaw” Indian Pomponio–because he wanted to paint him. In the meantime, David continued his research and the painting that he imagined is now a reality, part of a show of his latest work at the Bucheon Gallery, 389 Grove St, San Francisco. (415.863.2891…email [email protected]) David’s show opens on Friday, July 27, 7-10 p.m.

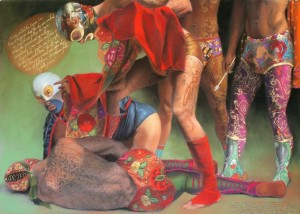

(“La Caida” 2008. Pastel and Gold Leaf on Paper. 56×38 inches)

————-

June, ….I would like to do more on the Pomponio theme, though. He is a background figure, so I am sending you a picture of the whole painting and also a detail of just the Pomponio figure. It’s a large pastel. The figures are almost life size. It is called “La Caida.’ It is a self-portrait.

I am the figure in the middle, bending over with the red cape. I am wearing the mask of St. Thomas Moor Killer, or Matamoros, who was believed to help the Spanish when they fought the Indians, and on my leg is painted Father Junipero Serra carrying Carmel Mission in his arms, with the rest of the missions scattered as Tattoos across my body. I mean to suggest that I am embodying the idea or spirit of both Junipero Serra, a man I believe tried genuinely to do good but who had an ambivalent effect on California history to say the least, and the malign idea of a Saint who kills Indians, both of which were brought to California and are integral to our history.

The man on the floor is a figure who appears in many of my paintings. It is unclear if he has been knocked out by the Serra/St Thomas figure, while also being aided by him.

The woman is the Aztec goddess of Mercy, Tlazolteotl. Her symbol was her black mouth. Her name literally means “Filth Eater.” In Aztec culture, you had one opportunity to confess your sins in your life, and when you did so, Tlazolteotl ate them and released you from their burden. I was thinking of her as being sort of the referee.

And in the background, to the far right, you see Pomponio, another ambivalent figure, but one whom I prefer to think of as a resistance fighter.

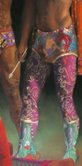

I read in another source that at the end of his life, Pomponio was brought in chains to the Presidio, and at night he cut off his heels to escape his shackles. They caught him by following the trail of his blood. I have also read that this is probably a later myth, but it is a powerful image, and since in much of my work I think of history as being a sort of myth, it applies well; on his shorts you can see him squatting down and cutting off his heels.

From the wound spring both blood and water, symbols of life, death, and also renewal. His boots are crocodiles–in Mesoamerican myth, the crocodile was thought to be the base of the world. This thus transforms him into an axis mundi, the world tree and the center of existence, which he is, as our ancestor (whether, in some genetic sense, if one were Native American, or Spiritually, as a forebear in this same land we now inhabit).

In the middle, on his legs, is painted a skull from which Pomponio emerges again, and again cutting his heel. From the mouth also emerges a world tree, which is also a path marked by his bloody footprints, leading to Chicomizoc, the Aztec place of birth and beginnings, and which is often thought to have been a place somewhere in the United States.

I often equate the bloody acts of our ancestors as a sort of sacrifice, however unwilling on the part of the victims, from which sprang the world we now inhabit, and which would have been impossible without that initial bloody scene. Along the path are scenes of conquistadors and massacre.

The last figure is Tezcatlipoca, the Aztec god of Change through Violent Conflict. The whole piece has been inspired by Mexican Lucha Libre. In my paintings contemporary individuals wear wrestlers costumes inspired by Pre-Colombian Gods, and by the historical figures so important to Mexican and California history, and they wrestle and act out these struggles which still have ramifications in our own day.

Anyway, those are some of my thoughts on the painting. I hope you like it, and I would love to hear your thoughts.

David Gremard Romero