The rescue ships carried the injured, stunned and stricken survivors back to San Francisco where they were created at the emergency hospital.

Rumor had it that attorneys for the San Juan and the S.C.T. Dodd scurried among the shocked survivors, urging them to keep quiet and avoid reporterâs questions. Clearly the attorneys were less interested in the passengerâs welfare than the liability of the ship owners.

Despite painful abdominal and spinal injuries, Theodore Granstedt could not be dissuaded from talking, charging cowardice on the part of the San Juanâs crew.

âWhen the crash came, the entire crew deserted their posts and saved themselves. They made no effort to launch a boat or save a soul,â? Granstedt said before nurses on the scene convinced him that he was seriously injured and needed to calm down and rest.

Theodore Granstedt had survived what the San Mateo Times called âthe worst maritime tragedy the Pacific Coast had experienced in more than a quarter century.â?

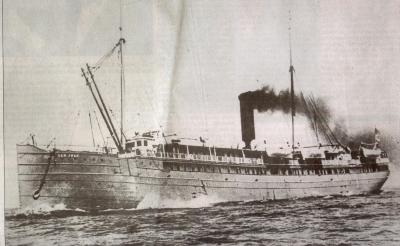

The Times noted that 72 peopleâmost of them passengers, many women and childrenâmet watery deaths as the Standard Oil tanker S.C.T. Dodd rammed the San Juan 12 miles off the San Mateo County coast.

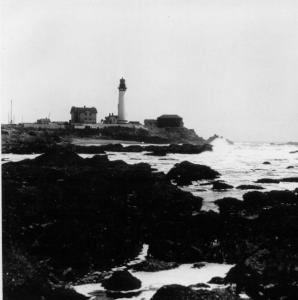

The following day Sheriff James J. McGrath and his deputies patrolled the coastline. Hundreds of curious county residents lined the shore as Coast Guard cutters continued a futile search for more bodies.

As the facts were gathered, the tragic story emerged.

According to survivors on deck at the time, the San Juan was sheared almost in half by thee heavy stern of the tanker Dodd and sank beneath the sea before most of the passengers in their staterooms, and the crewmembers in their bunks, had an opportunity to realize the vessel had been mortally struck.

There were indications that a terrific hole had been torn in the side of the San Juan by the impact and she started sinking at once. When the swirling waters reached the engine room, there was a hissing of steam and then the boilers explodedâshattering the ship from stem to stern.

Most of those fortunate survivors were on the deck or in the saloon at the time of the disaster. Those below in their berths or bunks were doomed.

âIt was not a matter of four or five minutes before the ship sank,â? Charles J. Tulee, the San Juanâs First Mate said. âIt was a matter of only a few seconds.â?

The second mate backed up Tuleeâs version, adding that the vessel sank as he attempted to help some women and children into one of the lifeboats. That lifeboat was the only one that might have been launchedâbut it was shattered in the boiler explosion, hurling the women into the air, injuring many seriously. Only a few survived.

Until the results of an official investigation there was the usual finger pointing. The owners of the San Juan blamed the tanker Todd, listing the heavy blanket of fog that covered the Pacific at the time as a contributing factor.

Just as insistent was the Doddâs Captain Bluemchen, who reported that in spite of the fog, the San Juanâs lights were visible, and that she suddenly changed her course, cutting across the Doddâs pathway.

As Captain Asplund had perished in the disaster, the authorities would never know his version of the events.

Some critics opined that the San Juan was too old to go to sea, but others commented that the steamerâs hull had been inspected by officials and pronounced seaworthy.

Captain Frank Turner, a federal steamship inspector, added that the Titantic was a new ship but she sank almost immediately upon receiving a blow comparable to the one suffered by the San Juan.

The bickering and accusations continued until the official inquiry, including a trial, was completed.

According to reports, the U.S. Steamboat Inspection Service Board found the San Juan inshore of the Dodd, tried to cross the oil tankerâs bow, was rammed and sank within a few minutes on August 29, 1929.

In other words, responsibility for the San Juan disaster was placed squarely on the shoulders of Captain Asplund. This decision did little to mitigate the suffering and loss of life.

The sinking of the San Juan remains one of the worst maritime tragedies that ever occurred off the San Mateo County coastline.

(The End)

(At right: Theodore Granstedt. Courtesy Patrick Moore, click

(At right: Theodore Granstedt. Courtesy Patrick Moore, click