Josiah Parker Ames

By June Morrall

The few clusters of Americans scattered in the bureaucratically named Department of California felt threatened on the brink of the U.S. war with Mexico in 1846. The settlers smelled invasion in the air. But from whom? They weren’t certain. They feared the Indians who could set fire to their homes and crops; they feared the Mexicans who could take away their livelihood, but for a time these isolated Americans whipped themselves into a frenzy against their old enemy England.

And why not fear England? At that very moment Admiral Seymour of the British Fleet was rumored to be sailing for the Pacific Coast. The settlers wondered if his orders were to take California. The editors of English publications supported the efforts of any country but America in a California takeover. The nerves of Americans were not soothed by the fact that until 1846 England and the U.S. jointly held Oregon.

However, the English decided that Cailfornia was not a plum worth fighting over; or else, as Josiah Royce, author of California, published in 1888, suggests, the British agents were not ready when the time came to strike. After all, it was the United States that went to war with Mexico and won handily in 1848.

Josiah Parker Ames was an Englishman who did not alarm the settlers when he appeared in Half Moon Bay about 1858. Born in England, but reared in New York City, Ames was 20 when he joined Colonel Jonathan Stevenson’s special regiment that sailed around Cape Horn to Califonria in 1847. The colonel’s instructions were to take part in the American occupation and to make the inhabitants “feel that we come as deliverers.” With the completion of the mission, Colonel Stevenson bought a rancho in Contra Costa County. His objective was to turn the land into a large, prosperous city. Josiah Ames followed in the colonel’s footsteps when he cast his eye on Half Moon Bay.

Already Ames had tasted the life of tents and cloth houses in San Francisco and the rawness of life in the gold mines. Filled with energy, he was now ready to buy land, start up businesses, and launch a political career.

Perhaps fellow “Regiment” member James Denniston invited him to the Coastside; they were close friends. After marrying into the Guerrero family, Denniston found himself the wealthy owner of an immense tract of land, called El Corral de Tierra, stretching from Montara to the Arroyo del Medio in Miramar. The creek running through the property in Princeton, where the family resided in an adobe, was named Denniston Creek. He operated Old Landing, where little steamers stopped to load produce in the 1850s.

Jim Denniston was politically powrful. During a trial in which he was the defendant, the jury did not bother to rise from their seats to deliberate elsewhere. They acquitted him on the spot.

While living in Half Moon Bay, Josiah Ames found romance. In 1861 he wed Elizabeth Freeman at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in San Francisco. The happy couple lived in a new 12-room house with ocean views. The San Mateo Times & Gazette gave the house the nod: “It is decidedly the finest dwelling on the other side of the mountain.”

Already a county supervisor, Ames now took office as county treasurer.

Josiah Ames was involved in much of Half Moon Bay’s miniscule economy. In 1873 when seven hundred citizens lived in Half Moon Bay, the flour mill he owned turned out 50 barrels of flour per day. He supplied the town with water. He was the proprietor of the Half Moon Bay Liversy Stable at Kelly and Main Streets.

“J. P. Ames has selected and stocked one of the best equine establshments on the coast,” boasted the Gazette. Perhaps he rented horses for the Fourth of July races at the Half Moon Bay Trotting Track. But there were hard times, too: In 1869 Ames’ good friend, 45-year-old Jim Denniston died of Bright’s Disease. Ames’ wife died in 1871.

His most significant contribution was the building of a wharf and warehouse at the mouth of the Arroyo del Medio Creek in 1868. By this time Denniston’s “Old Landing” had slipped into serious disrepair, and the new wharf, called Amesport Landing, opened up a vital economic link with the outside world.

Ameport prospered in the 1870s. It seemed that San Franciscans could not buy enough Half Moon Bay potatoes. In 1874 the Monterey sailed off with six thousand sacks full. “This is almost like shipping coals to Newcastle,” remarked an amused newspaper correspondent.

The political star of J.P. Ames was rising when he donated a new flag staff to Half Moon Bay in 1876. The local paper described it as “a beautiful stick, with a small platform around the base.” The flagpole was planted on the southwest corner of Main and Kelly Streets.

While Ames reached new political heights as a state legislator, the booming potato business at Amesport fell into decline. A pesty worm had destroyed the crop, including future plantings. The little steamers started to bypass Amesport and finally Ames sold the wharf business to the Pacific Coast Steamship Company. But they were never able to duplicate the heady days of the 1870s.

The connection between Josiah P. Ames and Half Moon Bay was severed. He left the Coastside and was appointed the Warden of San Quentin Prision. He was 76 when he died in Martinez in 1903.

—————

—————-

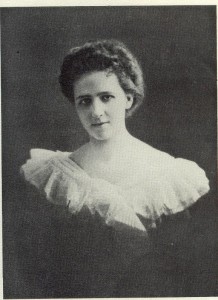

[Image: Mildred Brooke Hoover, author of Historic Spots in California, 1932. The Hoovers, Mildred and Theodore, lived south of Pescadero at Rancho del Oso. Theodore Hoover headed up Stanford’s Engineering Dept. The Hoovers were well liked in Pescadero, often inviting the locals to dinner.]

From Mildred B. Hoover’s book, page 328.

Amesport

A wharf erected in 1867 by Ames, Byrnes and Harlow on the ocean side of the county called Amesport Landing. It was located near the mouth of Arroyo Medio, a small stream dividing the properyof the two owners of Rancho Corral de Tierra. Warehouses used for the shipping of grain from this fertile region were built just south of the creek.

J.P. Ames, the leader in the activity, was a native of England who had lived east of the Missippi for some time before starting west as a member of Stephenson’s Regiment. The men of this regiment had been chosen for qualities that would serve them well in pioneer settlement after military duties should be ended. Ames was dishonorably discharged at Monterey in 1848, and coming to this vicinity in 1856, became county treasurer in 1862. He was appointted by Gov Booth to settle the Yosemite claims and was a member of the state legislature in 1876-77.

Amesport Landing was afterward acquired by the Pacific Steamship Company, which disposed in 1917 of the site of the old warehouses to the present owner of a small hotel erected there. The settlement is now called Miramar, where the weather-beaten piles of an old wharf may be seen near the hotel.