New Story by Michaele (Mikie) Benedict

Email Mikie ([email protected])

A Terrifying Sea Tale

By Michaele Benedict

The abalone diver probably has forgotten all about the time Edward almost killed him, since he hasn’t gone after abalone for years—nobody has—and worse things surely happened to him in the years he was prowling the Pacific floor for the delicious mollusks.

Jack (I’m changing the names, though anyone who knows these two will immediately recognize them) lived next door to us in the canyon. He was a romantic figure, tall, smiling and confident, the son and brother of fishermen. He ran the Abalone Shop in Princeton, assisted by his beautiful wife and by sundry neighbors.

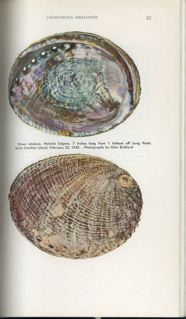

At the shop, they cleaned and pounded abalone and sold it, along with fish, sea urchins, and whatever was running. Now that abalone are rare on the California coast and no diving is allowed south of Mendocino, it seems surprising that there were so many of them in the early 1970s. Next to Jack’s house was a virtual mountain of abalone shells, strikingly fragrant on warm days.

Jack dived in one of those spaceman outfits you see in old ocean movies. Underneath it he wore a ragged union suit which we were convinced must have belonged to his father. He needed a tender, and he took Edward out in the boat with him one day to show him what a tender did.

Full of enthusiasm for the job, Edward got a tender’s license and went out with Jack, probably composing fish stories in his mind. But very soon after Jack’s helmet disappeared under the water, the boat began lazily rotating and Edward saw that the lifeline had become wrapped around the engine.

As he was trying to free the lifeline, he heard a muted voice coming through the air hose, saying “Get me out of here!” With a snarled lifeline, the only way to get Jack—weighing a couple hundred pounds in his diving suit—out of the water was to haul him in by his air hose, which of course cut off his air supply. The two of them had a tense trip back to the harbor. Edward, not noticing the motion of the boat while he was trying to untangle the lifeline, had dragged Jack off the reef. Jack had cut his weights, abandoned his catch, and surfaced twenty feet or more from the boat.

Edward arrived home pale as a ghost. When finally he could speak, he said “I almost killed Jack.”

The next day, he tried to get his money back for the tender’s license, since he was resolved never to go to sea again. I don’t remember how much money it was, but it was several hundred dollars, and his career as a tender had only lasted a day.

Jerry Brown was attorney general in those days, and Edward had known him slightly when they both lived in the same apartment house. Edward wrote him and asked to help get the money back for the tender’s license, and actually Jerry did just that, saying that fair was fair.

Jack donated the mountain of abalone shells to the KQED auction, and they brought a good price.