New-old story by June Morrall

[I wrote this in 1977]

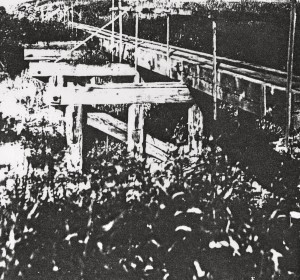

[Image below: Gordon’s Chute from “The Illustrated History of San Mateo County”]

Friends who heard rumors that a new toll road promised to link Woodside with Kings Mountain (high atop Kings Mountain Road) delivered the good news to Eugene Froment in 1867. They pointed out that future plans included extending the road to the Coastside. Froment, a native of France, who had recently logged in Santa Clara County, wasted little time before he invested his money near the picturesque Tunitas Creek south of Half Moon Bay.

While the prime timber land he bought dipped a thousand feet or more into the dark canyon, his property included 750 acres of redwoods which stretched for two miles toward the coast. At the same time Borden and Hatch logged the neighboring Purisima Canyon, Eugene Froment set up a shingle and steam powered sawmill near where Tunitas Creek meets Mitchell Gulch.

Inside the sawmill, measuring over 100 feet in length, visitors described two large circular saws, one mounted above the other. Here company employees, who numbered as many as 25-30 men, sometimes used blasting powder to split apart huge logs. After a long work day covering 11 hours, the mill turned out 18,000 feet of lumber. Most of this wood probably helped build the booming city of San Francisco.

By this time teamsters who hauled timber from forests near the mountain top, regularly traveled from the summit to the port of Redwood City, returning by nightfall. But Froment’s Mill stood further away in the isolated Tunitas; hauling through a roadless canyon was expensive.

When the new toll road failed to reach his mill, Froment formed his own turnpike company to cut hauling costs. A crew cleared the dense jungle of trees and built a road. But just as the toll road reached Smith Downing’s barnyard, a half mile from the coast, the company ran out of funds.

The men who drove for Eugene Froment spent a strenuous day hauling two heavy wagon loads of lumber, one at a time, from the mill to the summit. Here Froment built the Summit Springs Hotel as a stopover for these drivers.

But the majority of them preferred to rest near the Froment Mill office which stood at the top of the grade on a narrow ridge (between the headwaters of the Purisima and Tunitas canyons). The teamsters parked their wagons here and hitched them together before leaving on the last leg of their trip the following day.

The popular practice of staying overnight near the mill office, instead of the Summit Springs Hotel, baffled Froment. Soon even a boarding house and stable appeared at the flourishing lumber camp.

Although Froment obviously owned the lands, many of his employees built makeshift homes there with scrap lumber. Some of these temporary shelters offered more comforts than others. So when a family vacated one of the better houses, another family immediately seized it.

Without much level land available, the residents often liberated garden space from one another in the same manner. Up until that moment everyone called the camp, Gilbert’s, but soon a more descriptive name replaced it.

Early one morning as the Arnold family dozed peacefully, the sound of hammering rudely awakened them. When they peered outside their door, the Arnolds discovered a “neighbor” constructing a barn on what they formerly used as a vegetable garden.

The grabbing of land became viral, and somebody, believed to be one of the Arnold’s kids observed: “This place should be called ‘Grabtown.'” A place called “Grabtown Gulch,” a branch of Purisima Creek, apparently still appears on official maps.

After a good night’s rest at Grabtown, the drivers left for Redwood City in wagons pulled by glistening teams of horses. Their wagon wheels, with brakes set tight, easily slipped into deep grooves–long since worn into the dirt road–as they practically slid down Kings Mountain.

Any travelers, whose misfortune it was to head up the twisting road at that very moment were warned of oncoming traffic by the cloud of dust in the distance and the sweet jingle of bells worn by the horses. The clever traveler immediately veered to the widest spot in the road, patiently waiting for the procession to pass by.

Having to regularly travel over the big mountain was a tough way to do business, to deliver the lumber to the port in Redwood City. A Coastside railroad or sea route to San Francisco would have been more direct and profitable, believed Alexander Gordon, the owner of 1000 acres near Tunitas Creek. He thought a lot about building a port somewhere between Pigeon Point and Half Moon Bay. But the land Gordon owned was located at Tunitas, not the best choice for a port. Despite the extreme risks, he went ahead with the project, locating his unique shipping chute on sheer cliffs towering 150 feet above the Pacific Ocean.

Certainly observers labeled Alexander Gordon’s plan “crazy,” but Gordon remained optimistic. In his mind he visualized the lumberman Eugene Froment’s finished wood products and local produce sliding down the intricately constructed loading chute into a waiting steamer.

After toying with the idea, Gordon actually built the elaborate scaffolding, secured with wire cables that were connected to the rocks visible at low tide. When complete in 1872, sacks of potatoes and bags of grain stored in the warehouses above, slid down the 350-foot loading chute that could be lowered to the deck of vessels anchored beyond the surf.

But there were complications with “Gordon’s Chute.”

Ship captains would only approach the chute in fair weather–it didn’t make sense to tie up, in bad weather, to a reef at the unprotected site. And nobody realized that friction would cause the sacks of potatoes to burst open on the long way down the chute. The final blow to the success of Gordon’s Chute struck like a storm when a national depression severely hurt all businessmen.

Back at Froments mill, the lumber business appeared to prosper. Yet beneath the surface, the financial “depression,” combined with Froment’s increasing expenses, caused the company to suddenly fold. There was little fanfare when the San Jose Mill and Lumber Company took over the operation. They felled more trees from two to ten feet in diameter and by horse-and-wagon carried the finished product to the port in Redwood City. From there the lumber was shipped by rail to San Jose.

Not longer after both Froment and the San Jose Company filed for bankruptcy. Froment had owned an expensive home in Santa Clara but he now purchased an acre near the mouth of Tunitas Creek where he spent the last days of his life until he passed away in 1892.

Did Eugene Froment witness the fate of Gordon’s Chute. Probably.

While all along the sea worked overtime to undermine the chute’s wood framing, a severe southeast gale [which also damaged Loren Coburn’s chute at Pigeon Point] finished the job. According to reports, super-strength winds blew away the structure in 1885.

Alexander Gordon abandoned not only his famous shipping chute, but his nearby farm as well, moving to Redwood City where he opened a real estate business.

Next the Saunders brothers bought the Eugene Froment property. But when both brothers died within a month of each other, Clarence Hayward took over the shingle and sawmill. Hayward, whose father, Barzillai, operated a mill on Pescadero Creek, cleared out all the remaining timber, including one huge tree with twisted grain that other lumbermen had rejected. From this tree, which measured 16 or 17 feet in diameter, Hayward made more than one million shingles.

When Hayward completed his work, he sold the shingle mill to Borden and Hatch, who moved the operation into the Purisima Canyon. After fire destroyed the sawmill in 1907, the sounds of lumbering in the nearby Tunitas Canyon ceased—and all the inhabitants of “Grabtown” vanished, leaving no memories of their life there behind.

In 1913 mill owner John Dudfield finished his work on Pescadero Creek and he began searching for a new source of shingles. He finally settled on a small grove of redwoods in the once inaccessible Lobitos Canyon, where he found a foe in an early settler called W.S. Savage.

Savage had become a public advocate for the trees. He recalled that previous owners cut all their shakes, posts, pickets,and wood from this land, felling most of the biggest trees from 1860 to 1882. Since the 1880s the forest had returned to its original splendor and Savage now pleaded “for the last of the county’s giant trees.”

John Dudfield ignored Savage’s appeal and logged the small grove of redwoods until one day the mill suddenly shut down. Seven years later Dudfield returned, this time with “motor trucks” to haul the shingles to market. He did not quit until he was physically incapacitated by illness. Despite other logging operations in the area, virgin trees still flourish in the Lobitos.

———————

[Image Below: Leaving Tunitas, Ocean Shore Railroad Era. The driver of the Stanley Steamer i Joe Frye. The brakeman is Harry Staples.]

Story by

Story by