(Photo at right: Detectives search for human remains on castle grounds.)

In 1920 Pacifica’s gray castle stood alone in a veil of secrecy, isolated on a hill, even more mysterious when wrapped in a swirling layer of fog. It seemed out of place watching over the working class cottages below–yet neighbors were acutely aware of the regular flow of strangers coming and going.

There was reason to be watchful in 1920. Prohibition had gripped the country, and, initially, the stringent liquor laws were ignored and illegal roadhouses became the way of life in Pacifica.

The castle’s history was intertwined with the Ocean Shore Railroad, an iron road originally designed to carry funseeking passengers and local produce from San Francisco through the tiny beach resorts of Pacifica and Half Moon Bay, south to the popular resort Santa Cruz, and back again.

But by 1920 the Ocean Shore proved itself to be a dinosaur, unable to compete with autos and trucks. Tracks were never laid farther than a few miles south of Half Moon Bay. And by the time Dr. Galen R. Hickok, a Berkeley physician, purchased the castle, scrapping the limping railroad had become a controversial topic. Some in Pacifica worried that without the railroad, the artichoke industry would suffer–but ultimately all attempts to save the Ocean Shore failed.

Dr. Hickok didn’t move into the castle immediately. Instead he hired the Millers, an elderly couple, to tend the castle–but the doctor clearly planned to establish some kind of medical practice there.

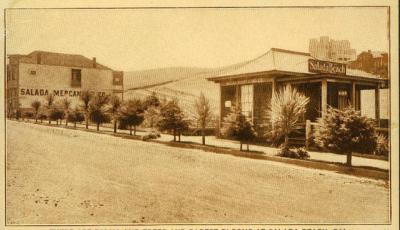

(Photo at left: See the castle on the hill behind the Salada Beach sign. photo Karin Murray)

(Photo at left: See the castle on the hill behind the Salada Beach sign. photo Karin Murray)

In 1920, toward the close of summer, the Millers suddenly left Salada for Ireland, and Hickok moved some of his belongings into the castle, including a bookcase of Shakespeare’s work, a gun rack with seven army muskets and a collection of antique swords that were nailed to the wall. Hickok also hired a nurse and housekeeper. It seemed like a modest beginning for his hospital.

Originally it was hoped the railroad would bring prosperity to the community but with its demise, isolated Pacifica became a haven for bootleggers and rumrunners. Surrounded by criminal activity spawned by Prohibition laws, Salada Deputy Sheriff E.J. Hutley became suspicious of everybody.

The gray cstle on the hill became a center of suspicion and was soon referred to as the “Castle of Mystery”.

Sheriff Hutley wondered why were the taxi cabs driving up the hill to the castle late at night?

His question was soon answered. Following leads, San Francisco and San Mateo County police had already been alerted that the castle was being used as an abortion clinic, “a retreat for girls and women unwilling to become mothers”.

Operating through a tip, two famous San Francisco police detectives posed for photographs on the hill, the castle looming behind them. Wearing his trademark homburg hat, Detective Miles Jackson stood beside matronly Policewoman Katherine O’Connor, one of three women on the force. Jackson was a tough cop who would later die in a shoot-out with gangsters.

Followed the press and their cameras, Jackson and O’Connor, walked across the grounds, opened the gate and knocked on the castle’s heavy oak front door. No response. They then rang the doorbell. Finally a stunned housekeeper appeared, insisting she had been hired a few days earlier and knew nothing. Her story checked out and she was not questioned any further.

Cleo Tevis, a uniformed nurse, was far more confident and accommodating.

“Come in,” she beckoned, according to newspaper reports. “We have nothing to conceal. The doctor is innocent of any wrongdoing.”

In the richly carpeted hallway, Detectives Jackson and O’Connor looked warily at the collection of muskets, swords and spears.

“They are decorations,” Nurse Tevis explained. “The doctor is a fine man and he’s done nothing wrong. No operations have been performed.”

But in rooms alleged to have been equipped in hospital fashion, the police found female patients, underage. The women told of visiting a surgeon’s office and then being taxied to the castle for “convalescence”.

Soon the castle was swarming with police, including Daly City’s Landini, San Mateo County Deputy T.J. McGovern and District Attorney Franklin Swaart who would try the case in Redwood City.

The press had a field day. At one point there were allegations of human bones found on the castle’s grounds, and although they led to sensational headlines, it came to nothing.

In early December 1920 Dr. Hickok went on trial for performed an illegal abortion. As the doctor shifted uncomfortably in his seat, a female witness testified that an operation was performed in a converted kitchen.

Hickok’s attorneys did their best to prove that their client was innocent but the case against Hickok was overwhelming, and the doctor was sentenced to San Quentin.

Soon after the trial ended, the castle entered another phase. Renamed the Chateau LaFayette, it became a lively roadhouse, raided repeatedly for selling illegal booze during Prohibition.

Predictably, at the end of Prohibition, the Chateau LaFayette closed down. The “Castle of Mystery” became neglected and sat unoccupied on the hill, a conversation piece for those who noticed its turrets from the roadside. To the locals it was a landmark used to measure distance from one site to another.

The castle became shabby and nobody seemed to care.

…To be continued….