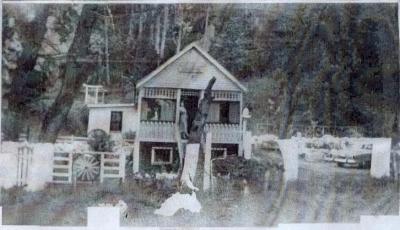

When I dropped in on Tom Clyne at the historic Mullen Farmhouse in east Miramar in 1977, the 84-year-old retired bookkeeper told me he had inherited the property from Clara Mullen.

Wow, I thought. What a great property. The Mullen Farmhouse stood at the far end of a dreamy country lane, itâs white paned windows barely visible from a favorite nursery of mine specializing in apple trees.

Clara–the last surviving Coastside Mullen– died of a heart attack in 1971. Tom did the books.

Was there a romantic link between the couple? I doubt it. Clara Mullen was two decades older than Tom Clyne. But although born in San Francisco, Tom Clyne spent the latter part of his days living alone in the Mullen Farmhouse, leaving only to drive to Pacifica where he swam laps in the high school pool.

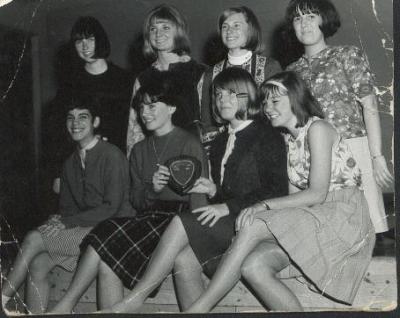

The old farmhouse was originally home to the Irishman John Mullen, his wife, and eight children, four boys and four girls.

There was Ned and Bill and Annie and Clara and Tom Clyne couldnât remember the names of the other two boys.

I already knew the background of the property when I visited Tom in the 1970s.

A century earlier the Pacific Steamship Company had hired John Mullen to run Amesport Wharf, today known as Miramarâand Tom added that Mullen purchased the beautiful property, within walking distance of Amesport, from the famous San Franciscan, Claus Spreckels, âthe sugar kingâ?.

Busy Amesport was a power point and John Mullen so famous that nearby Medio Creek was called âMullenâs Creekâ? by the locals. Memories of John Mullenâs presence hadnât faded much over the decades because I heard locals comfortably using âMullenâs Creekâ? in the 1970s.

In the Redwood City archives of the San Mateo County History Museum, Clara Mullen left us an anecdote about Amesport Wharf. She describes the tiny village of misfits and sea captains and deep sea divers as such a busy place that three small ships were loading and unloading supplies at the same time. Coal for heating was imported from far away England but the self-reliant Coastsiders planted fast growing eucalyptus trees and later cut them down for firewood.

Tom didnât change much inside or outside the old Mullen farmhouse, constructed entirely of redwood, and held together with square hand-cut nails–but he did like modern conveniences and installed electricity and plumbing. There was an outhouse but there also were two commodes (bowls) inside cabinets in the event you didnât make it to the outhouse in time.

Original furniture remained, chairs, a walnut bed frame and an antique secretary with hand carved handles. One entire room looked as it did 100 years earlier. I hope I get this right: throughout the house the walls were fashioned of âwood on woodâ?. In this one room I saw an old- fashioned wallpaper pattern. Tom explained that in order for the wallpaper to stick, a layer of cheesecloth was placed between the wood and the wallpaper.

The art on the walls was that of the easily recognizable local painter Galen Wolf, watercolors of Pillar Point, Devilâs Slide and the Hatch Mill that once stood south of Half Moon Bay. Also mounted on the wall was a special dinner plate, a reminder from the ill-fated T.F. Oakes, the iron ship that ran aground at the foot of Kelly Street in 1898.

I felt lucky to see the old Mullen Farmhouse . You donât get to do that often these days.

Before I left, Tom Clyne pointed out one more thing. Look closely at the white fence, he said. I saw a single red rose blooming. Look closer, he said, and youâll see a bullet hole. Just above the edge of the red petals, I saw it, the bullet hole.

Not long after the Palace Miramar had replaced the Amesport Wharf, one of the Miguelâs horses trespassed on the Mullenâs property, and John Mullenâs son, Bill, aimed at the animal but we donât know if the bullet hit its target.

But the small bullet hole in the fence, and all the possible stories you can imagine leading up to it, has fascinated me ever since.