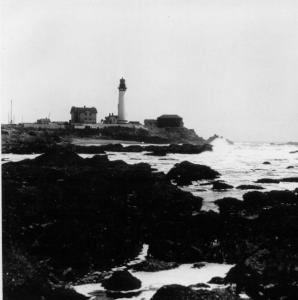

As the San Juan continued south past Pigeon Point, the Standard Oil tanker S.C.T. Dodd was plowing northward up the coast toward San Francisco, nearing the end of her voyage from Baltimore.

The vessels were 12-miles out, off the San Mateo-Santa Cruz coastline when minutes before midnight the sound of a piercing whistle broke the stillness of the night.

Without any further warning, the sickening shriek of metal tearing metal roared through the San Juan’s staterooms. The Granstedts were thrown from their berths. Hearts pounding, pulses racing, the panicked couple threw on clothes and fled to the deck.

The oil tanker Dodd had rammed the San Juan and the old steamer was sinking. Once on deck, the Granstedts encountered an eerie scene of terrified passengers and crew dashing about madly—and the smell of fear was pervasive. Theodore Granstedt saw no order, only chaos.

Some passengers jumped overboard, others were swept away by the powerful waves. Through the foggy mist, Captain Asplund could be seen trying to help women into a lifeboat.

There was no time to reflect, hardly time for prayer: It all happened so fast.

One second the Granstedts were standing beside their good friends, John and Anna Olsen, and their daughter, Helen. The next moment the San Juan was plunging stern first into the sea, creating a whirlpool that sucked them all in the abyss.

Then there was a great and very loud explosion.

Of the original group, only Theodore Granstedt survived. The next thing he knew he had surfaced from beneath the cold water. Searchlights illuminated the sea littered with wreckage—but he did not recognize the faces of people struggling in the nearby surf, clinging to toolboxes, screaming for help.

Miraculously, before the seriously injured Mountain View man lost consciousness, he grasped the piece of floating debris that saved his life.

By now lifeboats had been launched from other vessels in the vicinity: the oil tanker Dodd, the lumber carrier Munami and the motor-ship Frank Lynch. Theodore Granstedt was one of the 38 surviving passengers and crewmembers.

Wife, Emma, whose anxieties were sadly proven valid was one of 72 presumed dead…as were the Olsens and Stanford student Paul Wagner.

Although many of the San Juan’s survivors were crew, Captain Asplund went down with his ship as did the purser, Jack Cleveland.

…To be continued…

(At right: Theodore Granstedt. Courtesy Patrick Moore, click

(At right: Theodore Granstedt. Courtesy Patrick Moore, click

Sybil Easterday’s rooster should have awakened her from her deep sleep on the morning of April 18, 1906. Instead the well known eccentric sculptress, who lived with her mother, Flora, in an artistic home at Tunitas Creek, south of Half Moon Bay, found herself captive to the sudden shaking and moving of the earth.

Sybil Easterday’s rooster should have awakened her from her deep sleep on the morning of April 18, 1906. Instead the well known eccentric sculptress, who lived with her mother, Flora, in an artistic home at Tunitas Creek, south of Half Moon Bay, found herself captive to the sudden shaking and moving of the earth.