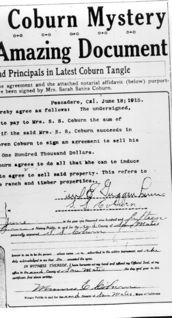

In his July 30th report, the handwriting expert Chauncey McGovern raised grave suspicions. He advised all parties that the signature was not that of Sarah Coburn. There were too many variations, he noted, between the signature on the will and the one on official records.

The âsâ? and the subsequent âaâ? on the official documents, for example, were not connectedâbut they were connected on the alleged forgery. On the official documents, the âaâ? was executed with one stroke, while it took two strokes on the will. In the authentic signature, the final âhâ? in the name, Sarah, âfaded out in a flourishâ?. In the will it looked like a drawn line.

Finally, Chauncey McGovern pointed out that the will was typed on a typewriter of âancient vintageâ?. Only Sarahâs signature was actually signed by hand. The letters and the alignment indicated that the will had not been typed by a stenographer â and, in his opinion, not in a lawyerâs office.

Did Sarah Coburn know how to type? No one knew for certain.

McGovernâs report did not speculate on who the alleged forger might have been.

In 1920 the will contest was dismissed when a financial agreement was reached between the beneficiaries of Sarahâs will and the East Coast relatives. By that time, the plaintiffâs attorney Charles Humphrey had acquired a desirable stretch of South Coast property. At the scenic Pescadero ranch he now owned, Humphrey entertained a steady stream of guests until his death in the 1940s.

A year after the case was dismissed, Chauncey McGovernâs ad seeking artists to rent the Von Suppe Poet and Peasant Cottage in Montara appeared in the Half Moon Bay Review.

In the early 1990s the cottage still stood in Montara, across the way from the old Montara Schoolhouse on Sixth Street. At that time, maintaining its tradition, the Von Suppe cottage was home to a music teacher.