A new-old story by June Morrall

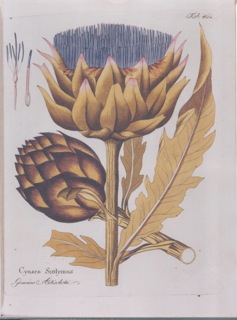

A Story about the Arti-Choke

When a truckload of Half Moon Bay-grown artichokes was donated to the Volunteers of America organization in San Francisco in 1928, the thorny vegetable with delicious leaves and a soft edible heart was so unknown that no one knew how to eat it.

Lack of knowledge about the “choke” short for artichoke, was a tad bit intimidating g for the city folk.

But this was San Francisco, a city, free and easy, ready to try something new. One poor fellow devoured his, leaves and all, nearly choking to death, according to newspaper reports. A second smothered the tender leaves with ketchup. A third soaked his daintily in a bowl of steaming hot soup.

When yet a fourth diner mistook the exotic vegetable for a table decoration, and another commented: “It looks like a blooming begonia,” the manager thought it was time to post a sign with instructions on how to consume an artichoke.

Strange as it may seem, many people really did not know how to eat an artichoke.

The key to popularizing artichoke consumption, produce brokers believed, lay in cultivating the public’s taste. This was accomplished by pointing out the artichoke’s distinctive flavor like this: “…so different from other vegetables that one usually has to acquire the taste for artichokes in much the same way as olives,” explained the Half Moon Bay Coastside Growers Association in a period pamphlet.

The goal was to replace the equally exotic asparagus as the first place choice with the consumer. And while it is difficult to imagine any similarity between asparagus and artichokes, the HMB Grower’s Association held that “the artichoke is eaten much in the same way as the asparagus.” It’s likely that the only thing that the vegetables shard is that both could be boiled, banked, or friend.

Then there was the nutritional value. Artichokes had iron but the publicists may have pushed their case too far when they also claimed that chokes were “universally recommended by doctors and served generally in hospitals.”

One legend has it that a group of famous pugilists brought the artichoke to the top of the page as a result of their visits to Half Moon Bay. Champion Boxers like Battling Nelson, Sharkey and Jimmy Britt left their training camps at Colma to train along the sandy beaches at Half Moon Bay in the early 1900s. Always, not far behind, were the sports reporters and their endless questions, seeking colorful quotes on upcoming bouts. The day’s training over, the boxers and reporters headed for a meal at the Half Moon Bay Inn on Main Street in Half Moon Bay.

Dinner always included artichoke “bottoms” with a puree of chestnuts, baked with bechamel sause, and a grainy coating of Parmesan cheese, all washed down with a glass of claret.

And that, according to legend, is what led to the planting of thousands more acres of artichokes.

[A little history: The farmers in Italy’s Po Valley were renown for the quality of their delicious artichokes they cultivated, and it is said that their descendants introduced the “mysterious” vegetable to Half Moon Bay. That’s one version.]

The Coastside provided the perfect climate for this so-called “edible luxury,” one that craved fog and moisture on its crown and leaves. To the choke, heat was anathema. A consistent dose of hot weather toughened up its otherwise tender disposition.

The first commercial plantings occurred about 1900. They were shipped to San Francisco, served as a specialty in the City’s finest Italian restaurant.

There was also an increasing demand from New York and New Orleans, but almost everywhere else the artichoke remained a mystery vegetable.

About the time of the San Francisco earthquake and fire, 1,500 acres were devoted to artichokes in Half Moon Bay and production increased annually. There was more curiosity about the finicky plant, and botanists were said to make annual pilgrimages to nearby Pacifica, where the silver-green plant also carpeted the fertile San Pedro Valley.

Tidy six-foot artichoke tracts stretched as far as the eye could see, and no where else in the world could they produce an artichoke of the size and quality as those on the Coastside.

With artichokes dominating the Coastal landscape, there soon came a time when Half Moon Bay’s agricultural industry was described as an “assemblage of houses entirely surrounded by artichokes.”

As it gained commercial acceptance, other California coastal communities began trying their luck with the artichoke. The fields spread northward to Point Reyes in Marin County and as far south as Santa Barbara.

This foggy sliver of coastal land was dubbed “the Artichoke Coast,” but Half Moon Bay was its capital, and Dante Dianda was the man known as “the Artichoke King.”

His fields were north of Half Moon Bay, in and around the El Granada area, covering 1,000 acres.

“It is there that Dante Dianda is the leading spirit in the California artichoke industry, and the man who has achieved the most in developing the quality of the California artichoke,” penned the Mercantile Trust Co. of California in an article.

If provoked, this volatile farmer could also be a difficult neighbor. When the inevitable encroachment of streets and side-streets threatened his crops in El Granada, he fought back by plowing up the pavement, throwing rich colored dirt on the sidewalks, and re-planting artichokes where there had been an attempt to pour concrete.

But it was that same energy that drove Dianda and caused Half Moon Bay to evolve as the major source of artichokes in the entire country.

It wasn’t often that the local winter was extreme enough to threaten the artichoke crop. In 1923, an unusual cold snap struck the Coastside, and substantial portions of the harvest were lost. Prices skyrocketed overnight from $8 to $20 a crate on the local market.

Coincidentally, the following year the the newfound popularity of the artichoke finally earned it the title of “King of Vegetables,” replacing the esteemed position long held of the long and thick asparagus.

In the mid-1920s when the government established standards for the globe artichoke, California was growing more and than the rest of the world combined.

There were attempts to open new markets by experimenting with the canning of artichokes, but the new process was quickly abandoned. The value was in the artichoke’s freshness and its ability to survive transport by land and sea. (It was years later that that artichoke hearts packed in jars with olive oil became an epicurean delight.)

Besides being shipped to San Francisco by truck, the chokes were also loaded on the Coastside’s Ocean Shore Railroad. But this method of transportation proved unreliable and fatal to the delicate vegetable as the train was often delayed due to falling rocks on the tracks at Devils Slide.

Through all, Coastsiders demonstrated their loyalty to the artichoke, and much of the yearly crop was consumed locally.

In the 1930s a new market was tapped. The best of New York City’s Italian restaurants developed a voracious appetite for the tender, smallest-sized buds, which were also the cheapest. They were dipped in batter and fried in deep oil and eaten whole, and as favored by the Italians.

It is said that an enterprising Los Angeles produce broker exploited the situation by shipping carloads of the smallest buds to the East Coast. They were then brought to markets on the West Side of Manhattan where the Italians resided and sold out in record time.

Push cart peddlers sold them like hotcakes. Price was based on the size of the bud, the larger, the more it cost. New Yorkers of every stripe were now enjoying the funny, mysterious vegetable.

But times were changing on the Coastside. By the late 1950s it was said artichokes were as hard to find on restaurant menus in Half Moon Bay as chestnuts. Coastside land was being swallowed up by developers.

As Half Moon Bay relinquished its coveted title as the capital of the “Artichoke Coast,” farms sprang up in Monterey County where today “chokes” have become the official vegetable.

—–

A new-old story by June Morrall