Story by June Morrall

Who was Iwan Dolgorouckoff?

There is something in me that welcomes mysteries. That want to solve them. Maybe that’s why I like the past so much. Mystery thrives in the past because if I have a fragment of an event, the people involved, the people who know, are usually gone. That turns it into a mystery. That means I have to put together what little I have and track down what I don’t have. Admittedly, I probably never solve anything; I just create a new mystery but I feel satisfied.

Like me, my dad kept stuff from the past. I don’t know how he managed to keep as much as he did. He had to move from WWII Berlin to Shanghai to San Francisco. My mom kept nothing. I’ll never fully understand her. The fact that she didn’t keep anything is a key to her personality. Just move on, nothing lasts, don’t hold on, or you’ll feel too much pain. She might have come to that conclusion after voluntarily leaving her home in Berlin to join the man she thought she was madly in love with, my dad, a half-Jewish man trying to survive in Shanghai.

She couldn’t have been certain that he loved her. In him, she may have seen the father she lost, shot dead on the last day of WWI in Alsace Lorraine, when she was just a girl.

My father,Charles, was an unusual man. Sensitive. Genuinely thoughtful and concerned, warm but careful in his selection of words.

Like me, dad kept scraps of paper, business cards, letters and envelopes with exotic foreign stamps. He kept the memorabilia for decades, and now I am the lucky recipient, and how I love the mysterious scraps of history that I have inherited. There are invoices with Chinese characters, good as modern art to me. There’s stationery from one of dad’s businesses, blank cream colored paper except for the name at the top: In bold black, “Continental Company,” followed by the Shangahi address.

And there are visuals, too, b/w photographs, plenty of them that lift the curtain of another t : In Europe, Berlin, London, Prague; In Asia, Shanghai, Hong kong.

A treasure for me.

One business card my father carried with him for decades fascinated me as much as the aquamarine ring my mother wore on her right hand. As a kid, the aquamarine ring always captured my attention. Its translucence, elegant square shape, the heavy frame of gold surrounding the soft blue stone. The ring seemed so big to me; I wanted it but thought there was no way I would ever get it. She told me dad had given it to her– and one day, to my total surprise, mom gave me the ring.

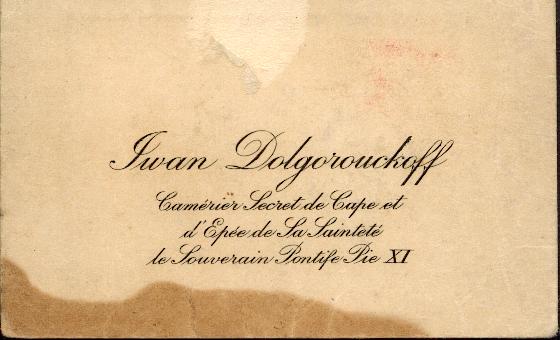

Dad kept a business card from Iwan Dolgoroukoff, an eccentric fellow he met in the famous Public Park (where Chinese were not allowed) in Shanghai. There, on the park bench, at one time, or another, my father encountered many of the fascinating exiles living in the international city. Iwan, a Russian, stood out for many reasons but on eof the things my dad couldn’t forget about Iwan was the expensive walking stick he always carried with him. The handle was a gold snake’s head, and when removed revealed a weapon, a sharp dagger.

As a mystery seeker, I could immediately understand the attraction to Iwan Dolgoroukoff, the man who carried a walking stick with a gold snake’s head.

That wasn’t the whole story, though. In time my dad learned that Iwan was in Shanghai, he said, on behalf of Pope Pius XI. My father was of the view that he might have also been a spy.

Would a real spy admit that he was a spy? There’s a mystery right there. I can only say that there was something trusting about my father that encouraged others to reveal dark secrets.

[And at that time, in Shanghai–in the late 1930s and early 40s–many spies were hard at work in Shanghai. Chiang Kai- Shek was trying to hold onto China as his nemesis Mao rallied the people’s loyalty. The Japanese were in town, too, running Shanghai by 1942 and every other country had an interest in what was going on there. Shanghai was, perhaps, the most European-looking city in China, partitioned into the French and English concessions, both marked by the presence of lovely European-style buildings. I saw for myself when I visited in 1984.)

I wanted to know who Iwan was. All I had was his business card.

First, I started calling sources in San Francisco.

I’m looking at a sheet of paper with scribbled notes all over it. I don’t write in straight lines; I write my notes at angles to one another. I began my search for information by calling the Italian Consulate in the City. I wanted to know what the words on Iwan’s card, “Camerier Secret de Cape et,” meant. Franco, an official at the consulate, said they meant: secret waiter or manservant. Whatever it meant, it was an honor bestowed upon Mr. Dolgorouckoff, and I wondered what he had done to receive such a special title. Franco and I talked some more and some of our conversation is recorded in the doodles on my piece of paper.

As we said goodbye, Franco advised me to call the Vatican Embassy in Washington, D.C. This was in January 1994, shortly after the death of my father. Now I was encouraged to write the Vatican’s historian, Prof. Carlo Pietrangeli, in Rome. This I did, and quickly received a letter in return—written in the Italian language, a surprise.

After receiving an initial response, here’s the letter I sent to Prof. Pietrangeli on February 4, 1994:

Dear Professor Pietrangeli,

I am most thankful for your gracious response to my small request desiring official confirmation of the status of Iwan Dolgorouckoff, a man my father met prior to WWII.

My beloved father passed away in 1992, leaving me, his only child, a fascinating collection of memorabilia reflecting his life spent in Shanghai between 1939 and 1946. My deep respect for my father has led me to study the diaries, documents and photographs that reveal his history.

Mr. Dolgorouckoff’s name card remains in nearly perfect condition after more than fifty years; he must have left a deep impression on my father.

I am sorry to bother you once more with such a small matter. I understand that it is not of great importance, but I humbly ask whether you might know why the Holy Father would honor Mr. Dolgorouckoff with such a special title? Would the title be equivalent to a knighthood?

Again, I apologize for this inconvenience.

Gratefully yours,

June Morrall

I have 3 letters from Professor Pietrangeli. Here’s his response, dated February 15, 1994:

Dear Mrs. Morrall:

With reference to your letter of february 4 I am happy to answer your query.

The Vatican State has several Orders of Knighthood. However the honour conferred on Mr. Dolgorouckoff is of different nature. He was named “Cameriere Segreto” and thus a member of the Papal Court personally at the service of the Holy Father.

I trust this will satisfy your curiosity.

With all good wishes, I am

Sincerely yours,

Prof. Carlo Pietrangeli

After receiving the correspondence, I spoke again with the Vatican Embassy in Washington, D.C. It was explained to me that there are a number of positions at an honorary level, unpaid positions. For example, when the Holy Father celebrates Christmas, he might invite Heads of State–and ask others to participate. Today they are called “gentlemen of Holiness,” but in Dolgorouckoff’s day, they were known as “Camerier,” or “waiters of the sword” invited to perform services during special ceremonies. Usually there were 12 “Camerier” in attendance.

[Perhaps “waiters of the sword” explains the unusual walking stick.]

Such an honorary position is bestowed upon someone who has performed special work or given a gift to the church.

I never did find out what Mr. Iwan Dolgorouckoff did to receive this special honor; I was told that meant whatever he did do was an act that has been kept confidential.

One of my contacts suggested I write to Rev. Thomas Brack at Maryknoll in Los Altos (some of whose Catholic missionaries lived in Shanghai during WWII).

My letter to Maryknoll was dated April 14, 1994. I stressed that “my curiosity” had not been satisfied by the Vatican’s note, and I wanted to know more about Mr. Iwan Dolgoroukoff, who, my dad told me, suddenly vanished in 1940. There were rumors among the Public Park crowd that Dolgoroukoff had been arrested by the Japanese and killed.

I wanted to interview any missionaries that had been in Shanghai during 1938-40.

Here’s the letter I received from Rev. Thomas Brack.

“April 21, ’94

“Memo to Fr Dwyer

“I understand how anxious June Morrall is to learn more about her father’s activities during his residence in Shanghai.

“Maryknoll Mission Society has had very limited association with the City or the area of Shanghai. Our mission areas were in the extreme south provinces of Kwangtung and kwangsi or north in Manchuria.

“In September of 1939 our American Passenger ship, bringing our newly ordained missioners to Hong Kong stopped briefly in Shanghai. That day Germany declared war on England and we left port with lights blacked out. No Maryknollers were active in Shanghai then or in the period from 1938 to 1947 except the following.

“Circa 1945 the Japanese army left Hongkong and China. I replaced Fr. Tennien as Procurator in Hongkong. Father Tennien spent 2 or 3 years in Shanghai, forwarding mission funds to the Maryknollers in the interior of China. About 1946/1947 Bishop James E. Walsh, M.M. worked in Shanghai until he was jailed there by the Communist Government. Both Father Tennien and Bishop Walsh have since died. I know of no other association of Maryknoll with Shanghai during that time.

“Fr. Tannien had a very astute bilingual Chinese as his secretary in Shanghai. If June thinks it worthwhile she might write him at the following address: Mr. Joseph Yuen (I’ve ommitted the address.)

“I know of no other Maryknoller who had connections with Shanghai during the period in question.”

That was almost the end of the line. I did write Mr. Joseph Yuen but have misplaced the letter. I’ll post his response as soon as I find it.

Yesterday, however, while searching the web for Iwan Dolgorouckoff, I came across an auction site that sold a very special incense burner and snuff bottle that had once belonged to Iwan.

This is what I found

Description:

Qianlong

Carved in medium relief around the flattened globular body with taotie masks divided by two large S-shaped handles, all between keyfret bands at the everted rim and spreading foot (cover missing), 13.5cm.(5 2/8in.) wide; and an agate snuff bottle, circa 1800-1860, the well-hollowed flattened circular body supporting a short circular neck, the translucent caramel stone with V-shaped white banding to the front and U-shaped to the rear, hardstone stopper,

6.2cm.(2 1/2in.) high (3)

du Boulay Collection nos.P223 and P116

Provenance:

P223

Lord Astor of Hever

Purchased from Christie’s, 7 April 1982, lot 362, for £230

P116

Iwan Dolgorouckoff Collection (formed in Shanghai between 1901-25)

Mr and Mrs Cox

——–

While I’ve solved some of the mystery of Mr. Iwan Dolgorouchkoff, I feel confident that one day I will uncover the rest of the intriguing story.

Update: I am learning much more about the mysterious Iwan Dolgorouchkoff and his link to Shanghai. Here is a photo courtesy of the Lemvig Museum. Statsbiblioteket in Aarhus (Denmark).