The Year I Had Mono by June Morrall

I was ten-years-old when I had monoâI still remember my dad looking at me and talking secretly with my grave-faced mother. I felt fine but they were talking about glands near my neck. The glands were swollen distorting the lines in my face.

My parents could see what I couldnât.

I was scared.

Dad took me to Childrenâs Hospital on Lake Street in San Francisco; later he said that he had to sell his car– I think it was a gray Studebaker– to pay the medical bills.

The diagnosis was mono, mononucleosis, then commonly called âthe kissing disease.â? When I heard thatâs what it was called I racked my 10-year-old memory trying to think of whom I had kissed.

Nobody!

Ten-years-old I might have been but I also had thought of kissing a couple of boys that lived in the neighborhood, the lower Sunset District in San Francisco, between the streetcar tracks on Judah and the ice cream store on the corner of Irving and 24th avenue.

Mom couldnât bear to come with dad and me to the hospital. I was deposited, and I did feel âdeposited,â? and my greatest fear was that I would not return home ever again. Maybe the hospital would be my new home, maybe home would be no place. Maybe my parents didnât want me.

The next thing I knew I was in a bed in a large childrenâs ward. Good thing my eyesight wasnât that good because I didnât want to see them anyway. I could feel their eyes on me, though.

My mother never came to visit, and my dad did when he couldâin those days you had to show up for work and I guess they couldnât get away. What I call a âfakeâ? aunt and uncle did come to see me. They lived nearby and were retired and always had books for me to read.

Thatâs what I did. I read book after book about kids older than me, enjoying life, dating and having adventures.

During the day in the big childrenâs ward room, a doctor came by and injected me with shots. When one arm became so used-up, so black and blue, the doc started on the other. At night when the room was black, without light, another doctor came by and injected my butt with something.

The shots hurt, and forever after, I did not look forward to anyone wielding a needle.

Two very lonely and long weeks after being a kid trapped in hospital, I was released looking forward to playing in the street–but now I learned that I couldnât leave the house for several months. I couldnât to school, play with other children; I was housebound with my non-English speaking grandmother as my guard. The doctorâs fear, I guess, was that I was contagious.

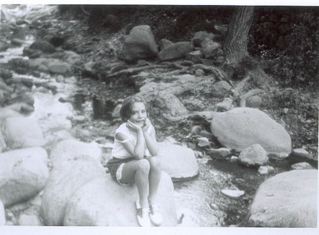

That was a bad year and it got worse. After I was released from the house, summer was over, and my parents had missed their vacation with me. It was the fall and while the other healthy kids went back to school, I went away for two weeks, not to Lake Tahoe, like we usually did, but, truth is, I canât remember. Was it Clear Lake? Was it Chico?

We stayed in a little cabin and I was left alone again and was walking around when I saw a big German Shepherd. On the ground near him was a long stick. My biggest mistake was to point at that stickâthe dog lunged at me and took a chunk out of my hand. The blood oozed up and started bleeding and it wouldnât stop.

I was scared.

If I told my parents, I thought, they would get mad at me, so I kept my bloody wound a secret. I ran back to the cabin (not knowing that while I thought I could move about unseen, I was dead-wrong, children are always watched) got some toilet paper and wrapped my hand in it. It was bleeding so much that I finally had no choice but to find my parents and tell them what happened.

Fortunately, everybody was loving and sympathetic. The big fear was that I would have to have the long series of shots for rabiesâbut the dog had had his shots. For a long time I had a scar on my right hand where the dog had taken a bit out of me.

I am looking at my hand now and I see that the scar has faded away.