Who Was Iwan Dolgorouckoff

By June Morrall

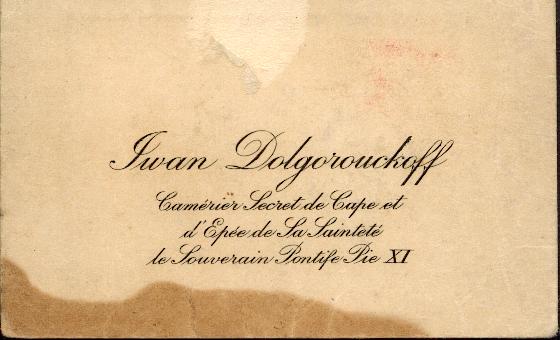

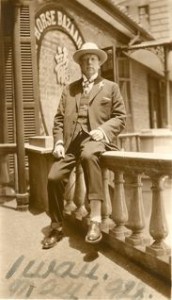

(Photos: At left, my dad sitting in Shanghai’s Public Garden, circa 1939, my collection. At RIGHT, Iwan Dolgorouckoff, courtesy Lemvig Museum, Denmark.)

(Photos: At left, my dad sitting in Shanghai’s Public Garden, circa 1939, my collection. At RIGHT, Iwan Dolgorouckoff, courtesy Lemvig Museum, Denmark.)

Recently I wrote a post which has become a favorite. It is called:�? Who was Iwan Dolgorouckoff?�? To read the piece, please click here

Iwan Dolgorouckoff was a mysterious character– with all the airs, pomp and accessories of British sleuth extraordinaire Sherlock Holmes. That’s how I would cast the Russian-Danish Iwan, if I were directing an early 1940s film noir.

Then in his mid-30s, my dad, a charming, movie-star handsome fellow himself, encountered Mr. Dolgoroukoff in Shanghai’s “Public Garden.�? This was the onset of WWII, a most extraordinary time in Europe and Asia. In the rural Chinese countryside civil war raged between Mao and Chang, while in Shanghai the war brought out the under side of everything you can think of.

To the Europeans living in Shanghai, the “Paris of the East” seemed to be at the end of the earth. Yet doom was a foreign army away in Shanghai, perhaps the last truly, open city, meaning that it was home to spies, beautiful ladies of the night and a buzzing black market economy.

And then there was the peace of Shanghai’s Public Garden.

Think about it: what better place to observe the tattering remnants of European civilization than from the banks of the Whanpoo River and the benches in the Public Garden? In Europe, at the brink of war in the 1930s, there was uncertainty, always someone chasing somebody else; one group dominating another.

The Europeans carried their intrigues with them to Shanghai and they felt safer than the majority left behind in Europe, where fear reigned and people suffered shortages of food and basic necessities. In Shanghai, there was a sense of calm, as if time was standing still. All the while, the free market was in force as the Chinese were accustomed to bargaining– and, with the right connections, most anything could be had for the right number after the dollar sign.

The Public Garden played friendly host to its European guests who surely discussed politics, world domination, and where to get sugar, butter, or the best cigar– while this grander, epic theme played out: Who was going to prevail? Who was going to rule the ground they stood upon?

After I posted the “Who was Iwan Dolgorouckoff” piece, I learned that Iwan was mentioned in a new book about the early beginnings of General Electric in China. Once the book was in my hands, I was surprised to see my first photo of Mr. Dolgorouckoff, confirming my father’s eccentric description of this unusual man.

The photo in the book was credited to the Lemvig Museum in Denmark. I googled the museum and emailed the archivist, asking permission to use the photo of Iwan Dolgorouckoff on my website. I scanned Iwan’s unusual “calling card�? (again, please see my original story for more details), and attached it with my email, then crossed my fingers. I hoped my email would be well received and was very excited about see an image of Iwan Dolgorouckoff for the first time.

Yesterday I received two emails from Ellen Damgaard at the Lemvig Museum. Here is one of them:

Dear June.

You can use the photos as you like on you website. The credit is: Lemvig Museum, Denmark.

I took a look at your website concerning Shanghai – that was really interesting, and I do think it is the right man. Your father’s description of Iwan’s appearance is very close to reality, and he seemed to be a strange person. I got the “Card�?, and will put it in our collection. We have some other photos of Iwan, and on one of them you can see a very special ring on his left little finger, maybe the poison ring?…

Kind regards

Ellen D.

(Photo: Iwan Dolgorouckoff, courtesy Lemvig Museum, Denmark.)

(Photo: Iwan Dolgorouckoff, courtesy Lemvig Museum, Denmark.)