Bring the troops here to fix Devilâs Slide

Yesterday, I left home in El Granada at 9:50 a.m.: it’s only four miles to Half Moon Bay but forty minutes later found me mired in traffic on two-lane Hwy 92 about a mile east of Half Moon Bay.

It was confirmed that there had been an accident–a big, locally owned commercial truck hit head-on and the traffic was impossibly backed up. As I crawled up the mountain I saw quite a few cars strewn on the side of the road, with steam spewing out of their overheated engines.

It took me 1 & 1/2 hours to drive from El Granada to 280 in San Mateo, a ride that used to take 20 minutes. The stagecoach in the 19th century did better.

(There was one benefit: at this very slow pace I enjoyed the beautiful coastside scenery that I hadn’t noticed in years when whizzing byâwhat a terrific opportunity to practice patience and meditationâ-unfortunately, the meditation led to drowsiness and I realized, with lids growing heavy, that I better stay alert or Iâd fall asleep at the wheel).

Later, on the way home (youâd better make your return early, or you hit the commute traffic and youâre back bumper-to-bumper) I shopped at the Half Moon Bay Safeway. Another âvictimâ? standing in the checkout line was calculating the cost of driving âover the hillâ? and back–$20 was his calculaltion. He was numbed by his own mathematics.

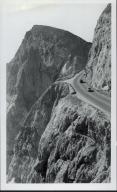

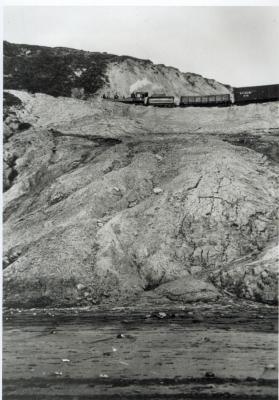

Itâs incomprehensible that there is no solution, even temporary, to reopening the breathtaking stretch of Highway 1 known as Devilâs Slide.

Itâs alleged by some that “the U.S. military can build a road anywhere in the world in about two hours”. Hey, how about bringing the troops to Devilâs Slide? It would give these young men and women a healthy and useful project to work on.

If getting the army to Devilâs Slide isnât possible, remember weâre just a stone’s throw from Silicon Valley and Stanford, the birthplace of high tech– and we âre drowning in Nobel Prize winners. Surely someone can come up with a solution to get Devilâs Slide re-opened.

In the grand scale of things, a broken road is a very small deal…but what if one day we had a real disaster like an earthquake or a tsunamiâ¦I shudder at the thoughtâ¦.

(At right: Theodore Granstedt. Courtesy Patrick Moore, click

(At right: Theodore Granstedt. Courtesy Patrick Moore, click

Sybil Easterday’s rooster should have awakened her from her deep sleep on the morning of April 18, 1906. Instead the well known eccentric sculptress, who lived with her mother, Flora, in an artistic home at Tunitas Creek, south of Half Moon Bay, found herself captive to the sudden shaking and moving of the earth.

Sybil Easterday’s rooster should have awakened her from her deep sleep on the morning of April 18, 1906. Instead the well known eccentric sculptress, who lived with her mother, Flora, in an artistic home at Tunitas Creek, south of Half Moon Bay, found herself captive to the sudden shaking and moving of the earth.