Is it coming Half Moon Bay’s way?

Created by June Morrall

Is it coming Half Moon Bay’s way?

Check it out: please click here

Story by John Vonderlin

Email John: [email protected]

Dave & Pat Andrews, please email [email protected]

I am working on a project and need to talk to you.

This Dave Andrews, please click here

Here’s a recipe for roasting pumpkin seeds, also known as pepita  please click here

please click here

Email John Vonderlin: [email protected]

Here’s a Frank Brophy ad for Princeton-by-the-Sea, circa 1908

Story by John Vonderlin

Email John: [email protected]

W. D. Potter Company, Inc. selling HALF MOON BAY LOTS

TWO NEW TRACTS

BEST OF ALL

The Miramontes Tract, the first tract thrown open to the public, has been sold. It was the first tract bought in Half Moon Bay and the first sold out. We have profited by experience. So may you. Tract No. 2 adjoins the Miramontes Tract No. 1. It is on high ground, like the Miramontes No. 1, opening into the main street of Half Moon Bay.

PRICES; $175 – $500

Be near the bank, good stores and the PostOffice–not near an imaginary city–a vision of the future

IDEAL VILLA SITES

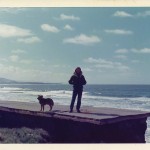

[Image below: 1970s: Standing on a slab of the “Ocean Shore Highway” at El Granada.]

The Great Storm of 1926

by June Morrall

When J.O Richards, chief engineer at the Point Montara Light Station, drove toward Half Moon Bay on a rainy Friday morning in February of 1926, he encountered the unexpected.

As Richards cautiously made his way along the wind swept bluffs in the small resort town of Princeton, he veered to avoid piles of driftwood strewn across the roadway.

And, as the downpour steadily increased, he swerved to avoid the impact of a giant wave heading for the windshield of his car. Slowly, he ground the automobile to a halt. Richards was visibly shaken, and when he got out of the car and saw the shattered windshield, he knew he was lucky to have escaped physical injury.

The next morning local newspapers described the alterations to the shoreline caused by “the worst storm in the Coastside’s history.”

A combination of driving rain and heavy seas savaged the stretch of coastline between Princeton and Miramar, heralded by Ocean Shore Railroad publicists in the early 1900s as one of the safest and most beautiful beaches.

The 1926 storm left its ugly mark on the beaches but some locals still remembered the whipping rain and wind of 1887 that claimed the Centennial Flag, then the pride of Half Moon Bay.The beloved flagpole toppled from its base and crashed through the ceiling of the Ames Saloon. At the time, the owner was out for breakfast and fortunately no one was hurt. But the saloon’s fancy chandeliers and lamps lay cracked and splintered across the wooden floor.

Although treated with wood preservatives, the flag pole, more than 100-feet tall, had rotted off at the ground and broke into several pieces. When it fell, the pole severed the town’s telegraph wires, temporarily cutting Half Moon Bay off from chatter with the rest of the county.

But in 1926 the storm’s most painful damage centered around the Prohibition beach resorts of Princeton and Granada where the powerful waves relentlessly smashed the fragile cliffs. In some places, the erosion reduced the distance between beach and the “Ocean Shore Highway” from 25-feet to a few inches.

You may not know that in the 1920s the road from San Francisco to Half Moon Bay followed a slightly different route than it does today. The highway 1 we are familiar with today was completed in the 1950s. But during Prohibition, beginning, say, at Montara, the Ocean Shore Highway turned east on Main Street, passing through Moss Beach along Etheldore Street. Then the road skimmed over flat country until reaching Princeton, with its three piers, where it turned south along Capistrano Road, following the shoreline for a short distance.

In Granada, the road turned eastward on Alhambra Avenue, then heading west into hotel-lined Miramar–where, in the 1970s, sections of the old crumbling roadway could be seen on the strand between El Granada and Miramar. Passing through the Coastside’s rich artichoke growing district, the Ocean Shore Highway reached Half Moon Bay.

Some oldtimers claimed the high tide at 9:30 a.m. on that morning in February 1926 was the highest level ever seen on the Coastside. For hours, big wave after big wave pounded the cliffs. And every third or fourth or fifth wave splashed up and over the highway, leaving behind a rubble of driftwood and pebbles,closing the roadway until workers arrived to clear away the debris.

The ocean’s waves swamped Artichoke King Dante Dianda’s ranch in Granada, and the land he farmed nearest Pillar Point Breakwater has vanished completely, eaten up by the sea. But For Dianda, worse was yet to come. Two months after the February storm, a large dam located on Dianda’s property in the back of Granada, burst, sending thousands of gallons of water spilling down the mountain-side. The tremendous water pressure pushed a vacation home some 600 feet from its original position. For hours 12 inches of slushy mud covered the roadway between Princeton and Granada.

During the Great Storm of 1926, piles of driftwood washed to within five feet of the popular Patroni House operated by Giovanni (John) Patroni, a prominent businessman and Coastside resident since 1902.

Also in Princeton, rogue waves wrecked both the 1000-foot Henry Cowell Wharf (which I think stood near Hazels, now Barbara’s FishTrap), and cement manufacturer Cowell’s warehouse. A small fish market, belonging to J.S. Bettencourt, was damaged beyond reognition and a donkey engine and pile driver were swept into the sea.

In Moss Beach, right there on the sandy beach, Charlie Nye’s famous “Reefs” lost its dancing platform, which was swept away. Nye always enjoyed telling guests that he had entertained the likes of author Jack London and horticulturist Luther Burbank. In Miramar, the once historic shipping wharf that could be seen from the big picture windows of Joe Miguel’s Palace Miramar Hotel lost a section of essential decking, leaving an empty space where there had been a connection to the mainland.

A month later when another devastating storm visited the Coastside, a combination of heavy rain and seas pummeled the Princeton=Granada-Miramar roadway, forcing automobile traffic to take a detour. By now only a few feet remained between the Ocean Shore Highway and the cliffs and there was a 30 to 40 foot drop to the beach below. Officials revealed plans to relocate this stretch of roadway, constructing what we know today as the beautiful shoreline highway running the length of California.

But both John Patroni and Dante Dianda strongly resisted change. They did not want to alter the roadway as it then existed, even if the storm was chewing up the cliffs. As they argued that Princeton’s hotels depended upon tourists using the old, shrinking road, the bad weather continued to force temporary closure of the Princeton-Granada-Miramar thoroughfare.

In a desperate attempt to save what Dianda and Patroni called “the prettiest and safest bathing beach on the Pacific Coast,” the farmer and the roadhouse owner offered San Mateo County officials the land necessary for construction of the new highway asking only that they build it as close as possible to its original location. To protect the new highway, they recommended building a sturdy rock retaining wall. Dianda and Patroni had the full support of the community; “roadviewers,” they were called, “voted” to keep the new road in the old location. But instead of curving into and out of the Ocean Shore Railroad- era towns of yesterday, when Highway 1 was finally completed in the 1950s, the new ribbon of road completely ignored them, looking neither east nor west, but just straight ahead.

Story by Barry Parr, Coastsider.com

Dear Coastsider Reader:

Power is down in our part of Montara, and we’ve set up shop at Caffe

Lucca on Highway 1, where they still have power and Internet access.

Share your reports of the Great Storm of ‘09 in comments on this topic,

or send us your photos and we’ll post them.

In the meantime, keep dry and stay home if you can.