When I first landed on the Coastside, and became intrigued with local history, I met with Louie Miguel, whose father, Joseph, was one of the masterminds behind the spectacular Palace Miramar Hotel. Louie offered good background info and also talked about the US military taking over his father’s buildings during WWII.

[The military moved into many of the Coastside’s public buildings, and most certainly, those located on the beach side of the highway, as the Palace was.]

Below: To visit the “California State Military�? website, click here

Camp Miramar

Story by Command Sergeant Major (CA) Dan Sebby

The former Camp Miramar was established on 21 April 1943 when the U.S. Army entered into leases with several land owners in order to provide for a camp to house infantry units assigned to the Western Defense Command. The 1 June 1943 edition of the Station List of the Army of the United States, issued by the Adjutant General of the U.S. Army, stated that a single rifle company, Company G of the 125th Infantry Regiment, was present at Camp Miramar.

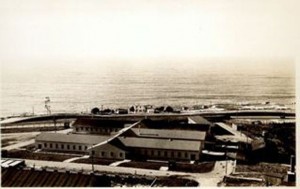

At the time of acquisition, there were two major buildings that the U.S. Army took control of. The first was the Miramar School, a small elementary school that served the local faming community and located on the eastern parcel, between State Highway 1 and Valencia Street. The other major building was the Palace Miramar Hotel and Resort, a large redwood-shingled building located on the beach in the western parcel of the Site.

- To these substantial buildings, the U.S. Army added several temporary barracks, mess halls and support buildings. These were of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) design developed by the U.S. Army Quartermaster Corps in the late 1930’s. These prefabricated, wood framed buildings could be assembled in as little as three hours by joining components with lag screws. Creosote soaked posts served as the foundation for these buildings. With the CCC buildings included, the post had a capacity to house 495 soldiers.

- Palace Miramar Hotel and Beach Resort in the 1920’s (www.halfmoonbaymemories.com).

In a letter to the Adjutant General, U.S. Army; dated 23 January 1944, the Western Defense Command identified the Site as vacant and excess to its needs. On 11 May 1944, Office of the Chief of Engineers at the War Department approved a request from the Bureau of Yards and Docks of the Navy Department for the six of the barracks and one on the latrine buildings. This transfer of the buildings to the Point Montera Anti-Aircraft Training Center was made without the U.S. Navy becoming responsible for restoration the land on which the buildings were situated.

From September until December 1944, the U.S. Army terminated its leases for the Site. A 1946 aerial photograph does not show any of the CCC buildings remaining. On 6 May 1952, the U.S. Army terminated its permits for water and sewer lines that ran along State Highway 1.

- Building Schedule

-

Facility Name or Function Quantity Building Type Size Mess Hall 2 CCC design 20′x130′ Barracks 3 CCC design 20′x130′ Barracks 2 CCC design 20′x120′ Barracks 3 CCC design 20′x100′ Officers Quarters 1 CCC design 20′x70′ Storage 1 CCC design 20′x40′ Storage 1 CCC design 20′x30′ Latrine 1 CCC design 20′x45′ Latrine 1 CCC design 20′x55′ Miramar School 1 Unlnown 3,500 square feet Palace Miramar 1 Wood Frame Sources: NARA Records, College Park, Maryland