She has 3 eggs, says Darlene Waegner of Half Moon Bay

To view, click here

(It’s off at late night)

Created by June Morrall

We just rented an “on demand” movie (“Flawless” with Demi Moore/Michael Caine) and were shocked/stunned to see it cost $10.99!!!! That’s DOUBLE the PRICE that it was just a few days ago.

Follow Author Richard Brautigan’s lead: Tell your own story.

And Michaele asks, “Did the famous Brautigan “Mayonnaise” Library make it to its new home at the Presidio branch library in San Francisco?…… Whether or not the collection actually made it, I have not been able to find out, despite many inquiries and phone calls to the Presidio Library.”

Telling Your Story

Story by Michaele Benedict

Story by Michaele Benedict

In his novel The Abortion: An Historical Romance 1966,

Richard Brautigan wrote about a library where anyone with a story to tell could write it out and put it on the shelves for others to read. The overseer of the library, which was open 24 hours a day, lived there. The fictional library was based on the Presidio Branch of the San Francisco Public Library,

Inspired by Brautiganâs idea, in 1990, the Brautigan Library was founded in Burlington, Vermont, by Todd Lockwood, a Brautigan fan, together with poet Robert Creeley and Brautiganâs daughter Ianthe..

Instead of the Dewey Decimal System, used by most libraries, the Brautigan library categorized its books according to the Mayonnaise System, referring to the fact that the library in the novel used mayonnaise jars as bookends.

My unpublished novel, The Dioscuri, registered with the Brautigan Library on May 25, 1990, was given the Mayonnaise catalog number LOV1990.05.003. The 325 books of the Brautigan Library archive (which included Brautiganâs typewriter) traveled to Seattle for a book fair, then back to its basement home in Vermont. It changed addresses in Burlington a number of times, finally winding up in the public library.

In 2005 the Fletcher Free Library in Burlington decided it would be fitting to ship the collection to the Presidio branch of the San Francisco Public Library. Whether or not the collection actually made it, I have not been able to find out, despite many inquiries. The last posted information about the move was a 2005 story in the Boston Globe.

What I wanted to talk about, however, was not the Brautigan Library  itself but rather the idea behind a library where everyone could tell his or her story, without the assistance of agents, publishers and editors. True, there is the Internet. But not everyone has access to a computer, and some people still like the idea of something written on paper.

itself but rather the idea behind a library where everyone could tell his or her story, without the assistance of agents, publishers and editors. True, there is the Internet. But not everyone has access to a computer, and some people still like the idea of something written on paper.

I spend at least four hours a day writing at the computer, mostly for fun these days, though occassionally I will send something off to a magazine, and once in a while something will be published. I am a hundred pages into âMurder at the Parthenon,â? a mystery novel set at a Tennessee newspaper in 1954. Certainly this effort is spurred by the love of the old newspaper technology, with its Linotypes and locked pages. I meet regularly with a writer friend so we can toss ideas back and forth, and nag each other about keeping our noses to the grindstones.

I am working on a biography of the pianist and Teacher, Egon Petri, part of which has appeared in magazines and on a piano pedagogy website originating in Finland, of all places. I am editing a wonderful work in progress by a friend who wants to tell her story about meditation. And I am proof-reading an exquisite collection of songs by a composer friend.

There is a modern facility which somewhat resembles Richard Brautiganâs library. My nonfiction mystery, Searching for Anna,  was published in February by Lulu.com. Lulu is an international print-on-demand publisher, some of whose thousands of titles strongly evoke those of Brautiganâs fictional library, such as âGrowing House Plants By Candlelightâ?.

was published in February by Lulu.com. Lulu is an international print-on-demand publisher, some of whose thousands of titles strongly evoke those of Brautiganâs fictional library, such as âGrowing House Plants By Candlelightâ?.

Anybody can tell a story on Lulu. For a small fee, a book can even get an ISBN number and be entered into Books in Print, which means it is available through outlets such as Barnes and Noble and Amazon.

Everyone has a story. Jung said that in most disassociated ânormalâ? living, oneâs story was often interrupted. He said psychologyâs primary function was to retrieve that story and reunite the individual with it.

One of the best pieces of writing I ever encountered was by a Skyline College student who had brought his essay to the Tutoring Center, hoping for help with his English. The story, laboriously written in longhand, was about how to wash dishes. The studentâs grandmother had taught him the proper way to wash dishes, and in the telling of the story, the student revealed himself: Loving, respectful, obedient, attentive to detail, humble. The language was awkward, but the story was truly touching.

How to tell your story: Hemingway said to place the seat of the pants on the seat of the chair and move the hand from left to right, or something to that effect.

I would add a bit about spelling and grammar, but it really seems to be mostly about having

something to say, saying it as honestly as you can, and then hoping somebody reads it and understands what you meant.

———-

Author Michaele Benedict lives in Montara. To read Mikieâs âSearching for Annaâ? website click here

âSearching for Annaâ? tells the heartbreaking story of Michaeleâs search for her beautiful young daughter, snatched from her Purisima home in the early 1970s. For info and to purchase the book, please click here. Email Michaele: [email protected]

That’s what I was told. (The photo was definitely taken in Moss Beach: everything is embraced by the fog.)

Notice, also, the way the chairs are made, the arts & crafts look, and compare them with the photo in the post below about Fanny Lea & Frank Torres. In the first photo of that post, the woman stands in front of a fence that strongly resembles the chairs in this post occupied by Mr. Wienke and his dog friend. Who made the chairs and the fences?

(Photo: Looks like early Moss Beach. Courtesy Millie Muller. Email Millie: [email protected])

A few days ago, I got an email from Millicent Muller, who lives in Farmville, North Carolina. Millie is a devoted genealogist who began researching her family roots in 1980, âback when,â? she explains, âyou actually had to handwrite a letter to the clerk of the court, asking for information. Of course, that included sending a check to pay for a copy, if there was a record.â?

Today Millie uses the Internet, including ancestry.com, with pouring in faster than before.

She began âsearching for a connection to Cherokee Indians on my motherâs side. Then I switched to my fatherâs side. Through him is the Frank Torres connection.â?

In the 1920s Frank Torres built and ran the popular roadhouse called âFrankâs,â? (today known as the Moss Beach Distillery.) He married Fanny Lea, who died on the Coastside in 1976.

Why does Millie want to know more about Fanny and Frank Torres?

Fanny Torres was Millieâs aunt, one of her father Howard Leaâs three sisters. Millie never met Frank or Fanny but âwould love to contact someone related to Frank Torres. That would probably have to be a grandchild of Frankâs who might have a photo of him with Fanny, someone who could pass along family stories. Iâd love either one!â?

HalfMoonBayMemories (HMBM)

Tell me a little about you. (Photo: Millie Muller)

Millie Muller (MM):

I was born in 1954 when HH ( my father Howard) was 64 years old. Everyone either called him HH or Old Man Lea. I had an older sister and yes a younger one. We were called The Lea Girls. HH married my mom when she was 20. She is still alive and remembers some things about what he talked about. To the best of my knowledge he never spoke with any of his family. HH died in 1966. He was 75 years old.

HMBM:

So you began your search.

Millie Muller (MM)

The first real information I got about Fanny came from a copy of my grandmotherâs death certificate. Her name was Martha Lea and she died in 1941. Grandmother Martha and Aunt Fanny lived on the East Coast and then suddenly moved to Moss Beach. But I donât know why.

HMBM:

What else did you learn?

MM:

It was my Aunt Fanny who provided the information on her motherâs death certificate. That was the first time I knew for sure that Fanny had been married, and what her married name was. And that was the first time I heard of Moss Beach.

HMBM:

What about Frank Torres?

MM:

It says that Fannyâs husband, Frank Torres, was the owner of the Frank Torres Beach Hotel on the Coastside. When I did an Internet search on the hotel, it brought up a page that shows the Moss Beach Distillery, and there was mention of Frank Torres.

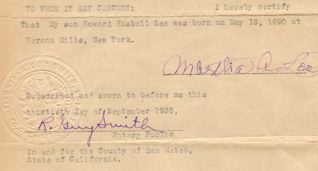

Three years before my grandmotherâs death, she drew up a document for my father. It was dated Sept 13, 1938, giving his place of birth and birth date. The notary was R. Guy Smith. I searched Amazon.com for books about the Coastside and found his name in association with some pictures in a book. That was very exciting for me!

HMBM:

And you also got Fannyâs obit, right? How did you get that?

MM:

I posted a query on rootsweb asking for information about Fannieâs obituary and burial. Within nine days, a lady called Colleen copied and posted Fannieâs obituary for me.

There was so much information in the obituary. Her funeral service was held at Cypress Lawn Memorial Park in Colma; her street address, Ocean Blvd. in Moss Beach.

Her husband, Frank Torres, was the owner of Frank Torres Hotel on the Coastside. She was a 47-year resident of the Coastside, a native of Verona Mills, New York. She was survived by her husband and four step-children: Frank Jr., Jacinto, Margaret and Nellie.

My goal is to learn as much as I can about these people. Why the move from New York to California? That would have been a huge move for a widow (her husband, Edwin Charles Lea, died in 1906) and her three grown daughters, Fanny, Alice and Maude.

HMBM:

Did you know Frankâs restaurant was a prohibition-era roadhouse?

MM:

I first learned about the prohibition roadhouse when I did a search on the Frank Torres Beach Hotel in Moss Beach. That search brought me to your website, and thatâs where I read about that.

HMBM:

Did you know there were rumors about Fannie working as a âmadam,â? running a bordello in the bungalows (now gone) next door to the roadhouse?

MM:

I had no idea about the rumors, and it doesnât bother me at all. Matter of fact, I got a chuckle out of it. My oldest sister, Wanda, her mother-in-law, ran a house in Norfolk, VA back in the day. Wanda passed in â96.

HMBM:

What else did you learn from Fannyâs obit?

MM:

In Fannyâs obituary, it says she was survived by Frank and four step-children: Frank, Jr. of Hillsborough; Jacino of South San Francisco; Margaret Rossi of Pacifica and Nellie Tooring of San Francisco.

If anyone has pictures of Frank and Fanny together, Iâm guessing it would be them or their children. So far I havenât found any information about themâbut I just learned about them.

Hereâs some background info about Frank Torres gleaned from food critic Ruth Thompsonâs 1930s book (âEating Around San Francisco.â?)

Born in Peru, Frank Torres left his home at the age of 14, and traveled the globe, trekking through Central and South America, Europe and the Philippines. As a steward on vessels that called at ports of the world, he âlearned to cook in every language.â?

He also rubbed elbows with the rich and famous, such as Alice Roosevelt, a cousin of Eleanor Roosevelt, the future First Lady. In 1905 Torres was present when Alice met and fell in love with Nicholas Longworth, a freshman congressman from Ohio. Their wedding, later held in the East Room of the White House, was to be the social event of the season.

About 1920 Frank came to Moss Beach. At first he had an âattractive rambling place,â? but in 1928 he built the new âbungalow restaurant.â?

The kitchen was commandeered by members of the Torres family, including Mrs. Torres, â a charming hostess,â? Frank, Jr., the chef, and Victor, who not only worked as a waiter but also played the piano.

In the eyes of food critic Ruth Thompson, Frank Torres âled a life of romance and adventure which makes the live of us ordinary stay-at-homes quite pale beside it.â?

MM:

I just found Frankâs name on the 1930 census report. Heâs number 185. And on the 1920 report, he is number 1418.

I think all this exciting!

HMBM:

Letâs talk about the photos a bit. The one of the lady with the white catâcould that be taken at the Distillery? I know youâve never been there, and the restaurant doesnât look like that today, but, to me, it feels familiar.

I was thinking the same thing about the picture of Martha (my grandmother) and the white cat. Two things: the color of the building and the archway shadow appear to be the same as in the photo.

According to the dates on the snap shots, the time frame is right for all the photos to have been taken in Moss Beach.

HMBM:

We all hope youâll solve the mysteryâand that someone from the Lea or Torres family will contact you soon.

MM:

Iâve been doing genealogy research on the family for several years now. I like to know the where for and what if about things. And I enjoy putting puzzles together. This is like one giant puzzle to me. I want to know things like, Fanny had a middle name and the initial was “P” but I donât have a clue what the “P” stood for. For Martha there was “A,” but I donât know what the “A” was for.

I would love to contact someone who was related to Frank Torres.

Email Millie Muller: [email protected]

Our friends, Reagan & David Luntz, proudly announce the birth of their new Wii and Nintendo DS game: “Ninja Reflex”

Our friends, Reagan & David Luntz, proudly announce the birth of their new Wii and Nintendo DS game: “Ninja Reflex”

To view the trailer, please click here

Who lived in the El Granada Bathhouse during Prohibition?

Story & photos by June Morrall. Bathhouse photo courtesy Redwood City Main Library.

I didn’t know anyone had actually lived in the El Granada Bathhouse–and used it as a home. When I arrived on the Coastside in the 1970s, the bathhouse was gone but I saw remnants of a road, big chunks of which had been and were still being torn apart by the highest of the high tides. If there had been a road there, then, clearly there had also been a lot of terra firma on the west side, the ocean side of the concrete, land once planted in rich fields of artichokes and Brussels sprouts. All gone now as Mother Nature shows us who rules.

The two-story “Bathhouse” was originally part of the Ocean Shore Railroad era, built in the early 1900s as a place for beach-goers to change into their bulky, old-fashioned swim-wear.

By now you know that the railroad’s “mandate” was to open up the isolated Coastside and provide the farming community with a new economy based on tourism. But Mother Nature, tough competition from the Southern Pacific on the other side of the hill, and a powerful love affair with the automobile took the Ocean Shore down.

Then the funniest thing happened: Alcohol, one of the popular drinks being whiskey was banned by the Prohibition Act, and, the dry law, like any law that says you can’t do something, encouraged the innovation of human nature to quench thirst. The natural response was to figure out a way to beat Prohibition. What the law breakers needed was a place to land the illegal booze, an isolated, secluded beach, recently abandoned by the railroad—and fearless men and boys to carry out the rest.

In the mid-1920s Gino Mearini and his family moved into the El Granada Bathhouse. Gino was just a kid, a teenager, smart as a whip, the son of Alesseio, who left his home in Tuscany seeking a better life in the US in 1914– at the beginning of WWI.

Alessio arrived without his wife and children; when he was doing better, he’d bring the family to live with him. The first job Alessio took was working in the dismal Pennsylvania coal mines before heading west to the Coastside where fellow Italians were farming artichokes and Brussels Sprouts.

(Photo: Gino Mearini stands in front of his bountiful orange tree.)

It was inevitable that Alessio would meet Dante Dianda, the big man in El Granada, the Coastside’s “Artichoke King.” Dianda, in partnership with John Patroni, who ran the Patroni House in Princeton-by-the-Sea owned two large ranches, encompassing Princeton, El Granada and Miramar. (Later, when Dante temporarily moved his family from El Granada to San Francisco, the farmer discovered that he enjoyed working at the busy San Francisco Produce Market much more than overseeing the two sprawling Coastside ranches.)

“Can you cook?” the Artichoke King asked Alessio Mearini.

“Yes!” was the younger man’s reply and Alessio was offered a job cooking for the men at the ranchhouse up the canyon in El Granada.

Alessio Mearini possessed a solid work ethic and business sense. Soon his cooking days were over and he was Dante’s partner, helping to manage the El Granada-Miramar ranch.

Earlier this week I was invited to Gino Mearini’s home in Cupertino. His lovely daughter, Janet Mearini Debenedetti was there, too–the owner of six cats, one of them most entertaining as she wrestled with Jo-Jo, Gino’s 10-year-old irresistible, recently shaved Pomeranian. Janet’s house stands across the street from her dad’s, and she said they bought the property on their street a long time ago, when the area was more rural. The climate reminded them of Italy, she explained.

We gathered at the kitchen table, a light-filled room (Burt sat across from me, with Gino at the head of the table, Janet at the opposite end. Janet grew up on the Coastsider, attending school with well known “Princetonians” Eugene Pardini and Ronnie Mangue.

I noted the small stack of books, all historical: Barbara Vanderwerf’s “Granada, A Synonym for Paradise;” Michael Orange’s “Half Moon Bay: Historic Coastside Reflections, ” and two of mine, “Half Moon Bay Memories: The Coastside’s Colorful Past,” and “Princeton-by-the-Sea.”

Gino wouldn’t like it if I revealed his age, but he has the spirit and curiosity of a young guy.

. (Photo: Gino Mearini looks at a page in Michael Orange’s book.)

Gino and his mom traveled from Italy to El Granada about 1921. At first they lived in a little house near where the El Granada Market stands today. A few years later the Mearinis moved into the vacant El Granada Bathhhouse.

The era belonged to Prohibition–and while the Bathhouse had become a home– when a light in the upstairs bedroom was flicked on past midnight, that was the “come on in, boys” signal–and the rumrunners boated in to El Granada Beach the bottles of whiskey unloaded from the Canadian mother ship anchored 12-mile out in the Pacific.

This was very, very serious business. Big money was involved. Thousands of cases of booze. The product had to be protected.

“There were bootleggers, armed with revolvers, looking for liquor hijackers at Miramar and El Granada,” Gino told me. But if it came down to a close chase with the Coast Guard, headquartered at Princeton, “We’d rather throw the load overboard than lose the boat. They had two Liberty motors, and they were fast engines.”

Gino, a teenager at the time, earned $25 for two hours of work, helping to drag the booze, that might have been tightly packed in gunny bags, across the sand dunes on homemade “sleds.” If John Patroni wasn’t around to pay Gino, “Otto and Anderson,” the Norwegians connected with the Canadian Mother ship, did.

What happened to the whiskey then? Gino said, “It was packed in straw, hidden in a nearby barn, and later picked up by some young guys driving a maroon colored Chrysler. There were velvet curtains covering the windows, maybe seven passengers could fit in there, boy, was it big.”

The drivers of the maroon Chrysler worked on contract, picking up at locations all over the county.

John Patroni was the “padrone,” the man who took care of the local Italians. He had nice cars, first a blue Packard, and then the fancy Cadillac. But who did John Patroni work for? I still can’t answer that question……

During our delightful conversation, Gino would correct things I had written. Clearly, while John Patroni had his own wharf at Princeton, where lots of whiskey was also landed, the El Granada Bathhouse may have played a much bigger role. In one of my books, I mentioned that booze was hidden beneath seawood mounted on a raft and pulled in. No, Gino said, “not possible.”

(Well, maybe it did happen but it sure sounds like nickel-and-dime stuff compared to the thousands and thousands of cases landed at El Granada.)

By 1933, the financial depression was hitting the Coastside hard, and because Prohibition was repealed, there was no more money to be made from illegal booze–but Gino had saved $600, all earned from working for the rumrunners.

The Mearini family moved out of the Bathhouse in February, 1932, and headed south of Half Moon Bay to isolated Lobitos where they rented John Meyn’s big white house. They later purchased land near where the trailer court is located on Airport Blvd., between Princeton and Moss Beach.

WWII on the Coastside is of particular interest to me, and Gino confirmed that all Italians without citizenship had to move from the beach side of the highway to the east side. (The Coastside Japanese had been interned.) In the town of Half Moon Bay, the center of Main Street was the dividing line. Gino had a lot of empathy for the “women and widows that had to move.” Unfortunately, most of the stores were on the west side of Main Street, causing much distress.

The Prohibition years were heady ones for the teenager, Gino Mearini, but one thing sticks out in his memory. At 6 a.m. in 1924, his mom called to him: “We’re going to get washed away.”

When Gino looked out the window he saw it coming towards him: a series of giant, hungry waves, an old-fashioned “Tidal Wave,”… a modern Tsunami. The family got out before the chicken house, packing shed and squealing pigs were swept away (the pigs survived.)

But when it was all over, the Bathhouse had been turned around a bit, and moved into the artichoke field. The beach around the house was gone. Years later as the sea chewed on more of the cliffs and sucked out the sand dunes, the waves finally claimed the Bathhouse as its own.

Occasionally, Gino Mearini visits the Coastside, and amusement crosses his face when he comes to the spot where the El Granada Bathhouse once stood. Actually, there is no such spot.

Over time the action of the waves has so altered the geography of what was here and what was there in the 1920s, that Gino can only smile and point, “The bathhouse, it’s out there, where the ocean is.”