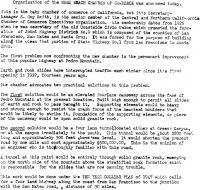

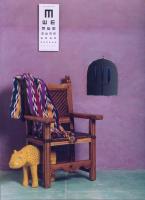

When I worked as the public information manager for Prevent Blindness in San Francisco, one of my projects was to design the annual report. One year I came up with the idea of using the Eye Chart as a piece of art and posing it with other cool furniture. In the end it wasn’t used, but I have always loved the picture and here it is:

< photo by Judy Howard.

< photo by Judy Howard.

I Went Shopping on Main Street

Do You Like Yours Tall, Thin and Twisty?

Main Street MakeOver–Half Moon Bay Inn: Before and After

Pink: In the light and dark

It Wasn’t Easy Being An Italian on the Coastside During WWII

In an earlier post, Ernie Alves (“Our Cows are Outstanding in Their Field”) hinted at the devastating effect of WWII on Coastsiders–especially Germans and Italians without citizenship papers–who were prohibited after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor from living or working on the west side of Main Street, the Highway 1 of that era.

What was on the west side of Main Street? The beaches, the stores, the school and the restaurant, the economic and social life’s blood of the town. Fear of another attack by the Japanese was so great that the military patrolled the beaches, built bunkers and placed gun emplacements on the hillsides.

I’d heard Germans and Italians were not permitted to cross the freshly painted white line down the center of Main Street, yet I didn’t meet anyone who would provide details until a couple of years ago when, through a phone tip, I interviewed Josephine Revheim. A Pacifica resident, Josephine had clearly suffered as a young woman but she had grown into a confident, articulate person who had done very well with her life.

At 15, Jo was the only daughter of Half Moon Bay farmer Antonio Giurliani and his wife, Marianna. The close-knit family resided in a little house next door to the old Catholic Church that stood west of Half Moon Bay’s Main Street. On the land adjacent to their home they grew sprouts and chokes.

The Giurliani’s came from Lucca, Italy, Jo’s father’s home, but her mom was actually born in Marseille, France. Still, everybody in Half Moon Bay considered them all Italian.

Soon after Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 army trucks rolled into Half Moon Bay, and, Jo told me, her father, who didn’t have citizenship papers, received an official letter from the US government ordering the family to move to the east side of Main Street. They had two weeks to comply.

Jo recalled seeing the printed notices on telephone poles throughout the town ordering all “aliens, Germans, Italians and Japanese” to relocate. The Japanese were rounded up and detained at Tanforan Racetrack. That history is well documented but in Half Moon Bay there was no central location for Germans and Italians. After registering as aliens in San Mateo they had to leave their homes on the west side.

(Technically, Josephine and her mom could have stayed on the farm but she asks: “How could we maintain a large farm without dad’s help?” The family decided to stick it out together.)

There were plenty of homes on the east side but unless you had a relative to help you were out of luck. That was the situation Jo and her family found themselves in–no place to move to and time was running out fast.

“Luckily,” Josephine said, “dad had a friend with a ranch in Higgins Canyon, south of town. He not only hired dad, he gave our family a place to live in the Johnston House. In those days it wasn’t called the Johnston House–we called it ‘the old house on the hill'”.

(Built in the 1850s by pioneer James Johnston, the fully restored Johnston House has become a famous landmark that stands on a hill at the south end of Main Street).

Josephine still recalls the morning her family moved into “the old house on the hill”. She says, “It hit us, what we were in for. The rat-infested house had no windows and vagrants had slept there, leaving behind garbage. Straw covered the dirt floors, the outhouse was halfway up the hill in the back, and when it rained it was like a waterfall, but there was plenty of room, and thank God there was cold running water to drink.”

Most important, the house was located on the east side of Main Street. But the school and the stores were on the west side. If they crossed the white line, they would be breaking the law. To check on their farm they’d have to do it secretly, because, if caught, it was likely someone would inform on them.

The most humiliating part of the whole experience for then 15-year-old Josephine were the stares and unfriendliness she and her familly encountered. One of the worst recollections was of her mother fighting off an assualt by some angry, unthinking local. It’s not hard to understand that many of her remembrances are so unpleasant that she remains uncomfortable talking about them today.

After about five months the Giurlani’s nightmare ended.

“We came home,” Jo says, “and at least the house and barn were still there. Everything else was gone, the crops were gone, and even our wild pigeons that had nested in the barn were gone.”

Not long after they settled back in their home the family received a letter from the US government advising them to become citizens or face deportation. They all got their citizenship papers.

Shortly after my interview with Josephine Revheim, we took a ride to Half Moon Bay to see the house she had lived in as a 15-year-old before her family was ordered to move out of it. Surprisingly the house was still standing, but it was vacant and uncared for, with broken glass on the floor, grafitti on the walls, empty paper coffee cups, somebody’s crashpad, and, right there, in the middle of town.

Why was this house still standing? Some connection to the story I’ve told?

Of course, I haven’t been back and don’t know if the house still stands but here are the photos I took a couple of years ago. That’s Josephine Revheim in all the pictures.

Postage Perfect

The Moss Beach Post Office gets high marks for balancing the books in 1917.

The letter (click to enlarge or read below) is from:

United States Post Office

Burlingame, Cal. Nov. 3. 1917.

District Postmaster.

Moss Beach, Cal.

I have received from you this date under register No. 59 stamped paper for credit amounting to $180.71.

It is a pleasure to receive a report correct. Would like to shake hands with you.

Signature illegible

Central Accounting Postmaster

I’ve Re-typed the 1952 Document

I decided to type the document called “Organization of the Moss Beach Chamber of Commerce was announced today.” (February 12, 1952).

In my previous post, you can click on the original and read it, too.

This is the baby chamber of commerce of California, but its Secretary-Manager R. Guy Smith is the senior member of the Central and Northern California Chamber of Commerce Executives organization. His membership dates fromm 1925 when he was secretary of the old Coastside Civic Union which promoted the formation of Joint Highway DistrictNo. 9 which is composed of the counties of San Francisco, San Mateo and Santa Cruz. It was formed for the purpose of building along the ocean that portion of State Highway No. 1 from San Francisco to Santa Cruz.

The first problem now confronting the new chamber is the permanent improvement of this popular highway at Pedro Mountain.

Earth and rock slides have interrupted traffic each winter since its first opening in 1937, fourteen years ago.

The chamber advocates two practical solutions to this problem.

The first solution would be an elevated four lane causeway across the face of Pedro Mountain at the present location. Built high enough to permit all slides of earth and rock to pass beneath it. Supporting elements would be heavy and strong enough to resist the crash force of the heaviest boulders that would be likely to strike it. Foundation of the supporting elements, or piers of the causeway would be upon solid granite rock.

The second solution would be a four lane tunnel located either at Green Canyon, or at the canyon immediately to the south. This tunnel would be about 2800 feet long and approximately 500 feet above sea level. It would shorted the present road by one mile and cost approximately $500,000,00. This is the opinion of an engineer who is thoroughly familiar with this road.

A tunnel at this point would be entirely through solid granite rock, emerging on the north side of the mountain above the stratified rock formation which is responsible for the slides that are now causing trouble.

This work would be done under the TEN YEAR COLLIER PLAN of 1947 which calls for a four lane highway along the coast from San Francisco to the junction with the San Mateo road, a distance of 30 miles.

1952: Moss Beach Chamber of Commerce Organized

Old Miramar Landmark Partially Destroyed By High Waves

The old landmark I refer to in the headline above was an historic wharf at Miramar, partly destroyed by huge waves in early November 1928 or 77 years ago.

About 150 feet of the wharf at Miramar Beach had been swept away by heavy seas and a team of men worked feverishly to retrieve the floating wood and debris.

It was originally known as Amesport Landing ( built by Judge Josiah P. Ames in 1868)–and after it was modernized, it was called Miguel’s Wharf, named after the Half Moon Bay family who built the beautiful glass-windowed and redwood shingled hotel called the Palace Miramar.

The pier and the hotel, once the site of Amesport Landing and a warehouse and customs house.

The pier and the hotel, once the site of Amesport Landing and a warehouse and customs house.

The wharf’s fame grew out of the Amesport, pre-Ocean Shore Railroad era when Miramar was the center of a tiny seafaring village, with a warehouse for shipping and receiving freight for the Coastside. There was a waterfront saloon and a customs house from which passengers bound for San Francisco boarded the colorful steamers “Maggie” and “Gypsy”.

(Valladao is a well known name in Half Moon Bay, and one of their family members, “J.C.” worked as a clerk in the custom’s office.)

It was Moss Beach writer, Peter Kyne, who fell in love with Miramar and the steamer “Maggie”, so much that he featured them in his first book, “The Green Pea Pirates”. Local legend has it that when Peter was a kid he watched the steamers stopping along the Coastside to drop a package of nails here and pick up a letter there.

Hearing about the pretty hotel, the wharf, the steamers and the writer who loved it all, makes you believe all was perfect in Miramar.

Nothing is ever perfect, and behind the facade was a longtime feud between the new hotel and wharf owners, the Miguels, and the Mullens, the former “power” at Miramar. The Mullens, whose lovely farmhouse still stands on the east side of Highway 1 in Miramar, had operated the Amesport Wharf until the landing lost its usefulness as a source of transportation and was plunged into bankruptcy.

Along came the Miguels with a well known architect’s plan for a beautiful hotel that would serve Ocean Shore Railroad passengers. The indoor salt water “plunge” and the restored wharf would knock the socks off visitors. It was inevitable that a confrontation would arise between the Mullens and the Miguels.

That story coming up soon!